December 24, 2025. The "Ala-Too" cinema in Bishkek was packed. At the premiere screening of the film "Tutkun," directed by Temir Birnazarov, a large number of viewers gathered, including fans of Kyrgyz cinema and representatives of the creative intelligentsia, weary of soulless comedies and monotonous plots. Some spectators even took seats on the steps, hoping for deep and honest cinema.

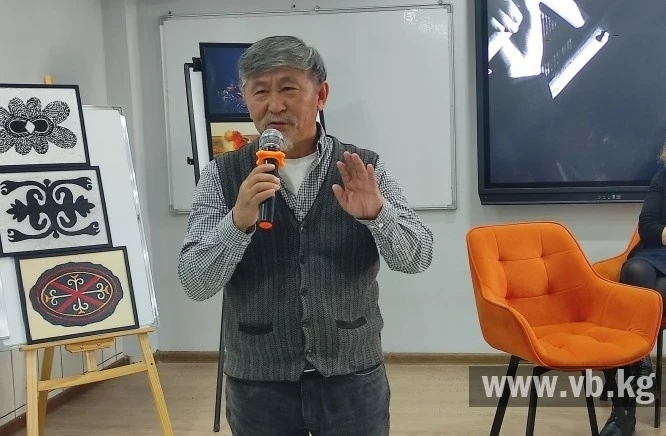

Temir Birnazarov, known for the film "Belgisiz marshruta" ("Unknown Route"), has gained recognition as a talented author. In turn, "Tutkun" is based on a story by Aslan Koichiev, who was recently appointed as the state secretary.

It seemed that all the elements for a successful film were present: a strong literary foundation, an experienced director, and state support of 24 million soms provided through "Kyrgyzfilm."

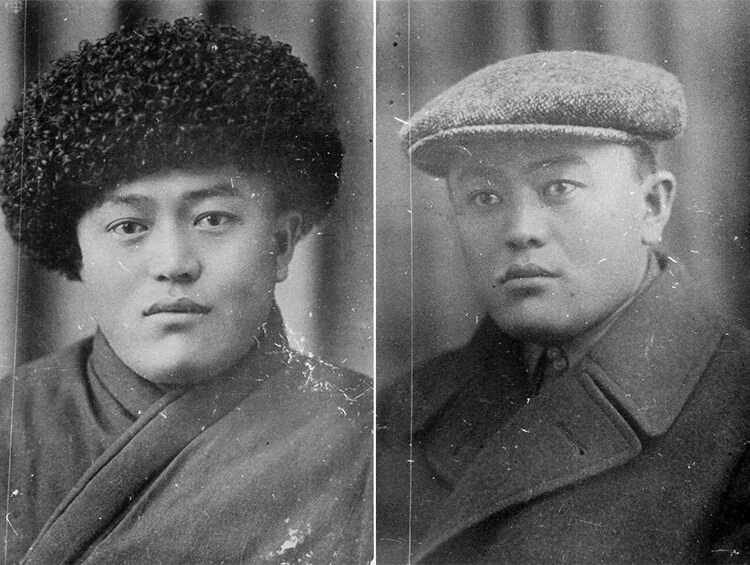

The plot of "Tutkun" focuses on the fate of Kalymurat, who, finding himself a prisoner during the war, remains in Germany and does not return to the USSR. He starts a family, marries, and raises his daughter Kanikei, but for decades he is tormented by nostalgia for his homeland. Memories of the past, his native land, and feelings of guilt never leave him.

Kalymurat regularly sends letters to official bodies in Kyrgyzstan requesting his return or at least a restoration of contact with his relatives. But no replies come. One of his letters attracts the attention of the KGB, which sees not a tragic fate but a potential threat.

A KGB representative finds a relative of Kalymurat in his native village and stages a "happy life" for the family without him, sending a letter to Germany in which Kalymurat is declared a traitor.

Upon receiving this letter, Kalymurat experiences a severe emotional blow. His last hope is shattered, and he dies in the hospital, unable to return either physically or symbolically to his homeland, in the arms of his wife.

The film ends on this grim note, leaving viewers bewildered: "Is that all?" The main character never finds himself in independent Kyrgyzstan, nor does he see the mountains that so often appeared to him in dreams. The theme of sovereignty remains unaddressed, and the story of a man who lived in captivity does not receive closure.

In the hall, there was a sense of confusion and disappointment that the film did not provide the expected meaning or emotional resolution.

The problems with the film begin from the first frames. For more than ten minutes, viewers observe a silent scene in a school corridor, where a KGB officer searches for a baskarma involved in a love intrigue. This does not create tension and is rather tiresome.

Next comes a scene with the same character, who is depicted almost like a folkloric hero, Apendi. The actor playing the chekist does not create the image expected of a security service officer; rather, he resembles an ordinary neighborhood policeman. The KGB storyline, which was supposed to be the foundation of the plot, appears flat.

When the action shifts to Germany, the film briefly comes to life. Kalymurat, now Helmut, lives with his wife Greta, engages in his favorite activities, and reminisces about his childhood. His daughter Kanikei brings a musical instrument from Berlin, but it turns out to be a dombyra, creating an obvious attempt by the director to touch upon the linguistic issue of the Soviet era. However, this theme remains underdeveloped.

There is not a single complete scene in the film where father and daughter communicate in Kyrgyz. If Kanikei does not speak Kyrgyz, why introduce this motif that does not lead to conflict?

Temir Birnazarov likely attempted to convey a deeper message than just a story about the tragic fate of a prisoner of war.

The film was conceived as a narrative about captivity without barbed wire and the tragedy of a torn identity.

However, the director lacked the artistic means to convey the emotional depth he aimed for.

The film lacks familiar dramaturgy, catharsis, and believable emotions. The ending remains hopeless, leaving viewers with questions. Moreover, Birnazarov chose a cold style, where the characters resemble symbols more than heroes with whom one could identify. This approach may enhance the philosophical subtext but negatively affects the emotional perception of the audience.

Thus, the film ended up between genres and expectations.

It could be perceived as a war drama, but it is not a film about war. It could be seen as a historical film, but history is not the main focus here. It could be categorized as a social drama, but it is too abstract. Ultimately, "Tutkun" did not align with the expectations of the audience nor with the typical festival format.

Viewers came to "Ala-Too" hoping to see a film on the level of "Belgisiz marshruta," perhaps even deeper and more mature. However, Temir Birnazarov presented a completely different film that, unfortunately, appears to be a step backward in his work.