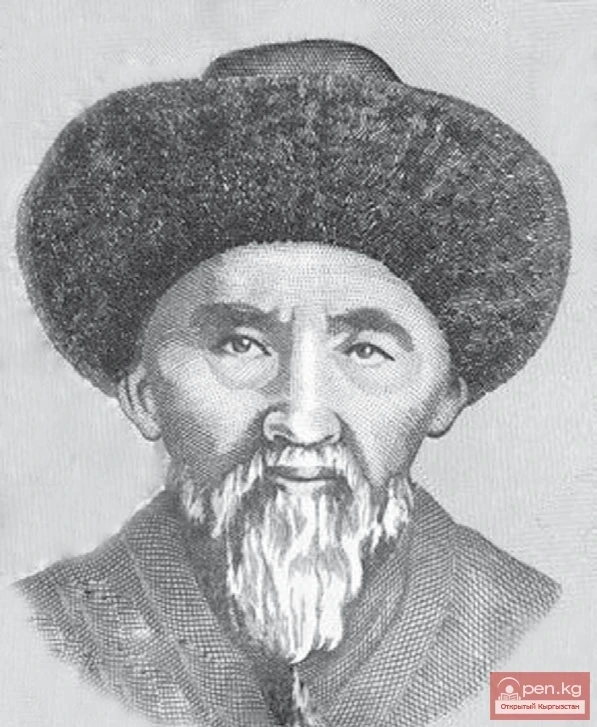

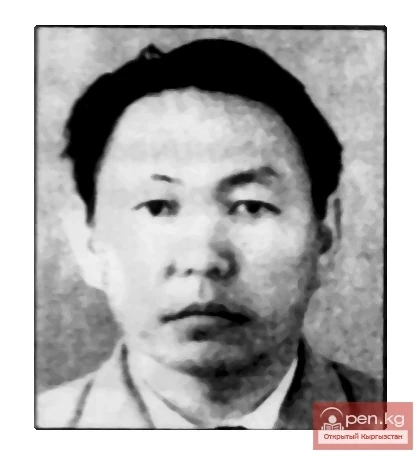

The first Prime Minister of the Kirghiz ASSR, Jusup Abdrakhmanov, performed a heroic act by stopping the famine that threatened his people and challenging the brutal Stalinist system. For his brave actions, he was recognized as a hero but was later shot due to his revelations in a diary that became a significant document of that era. His talent and courage were ahead of their time, and Abdrakhmanov's tragic fate became a symbol of his time.

In 2024, President Sadyr Japarov signed a decree awarding the title of "Founding Fathers of Modern Kyrgyz Statehood" to five outstanding individuals, including Jusup Abdrakhmanov. The head of state called for events to be held in their honor and emphasized the importance of preserving their memory for future generations.

The editorial team of 24.kg continues to explore the legacy of these great figures through the lens of their descendants. Jusup's great-grandson, Astemir Abdrakhmanov, shares new discoveries about the struggle for historical truth and the fate of his famous ancestor.

History finds new facets: how archival materials change the perception of the past

“It all started in 2021 with President Sadyr Japarov's decree, which initiated the celebration of Jusup Abdrakhmanov's 120th anniversary at the state level,” Astemir recounts.

This year became significant: the government committee began active research into the political legacy of the first chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Kirghiz ASSR. Conferences and exhibitions were held worldwide, from Kyrgyzstan to Turkey, and books were published. Monuments were erected in Ankara and Cholpon-Ata, and Jusup Abdrakhmanov posthumously received the title of Hero of the Kyrgyz Republic.

Astemir Abdrakhmanov was awarded the "Ak-Shumkar" badge not only as a descendant but also as a keeper of the memory of his ancestor. The awards and Jusup's diary were handed over to the President of the Kyrgyz Republic and are now kept in the National Historical Museum.

“But the most important thing,” Astemir adds, “is that by the order of the president, significant volumes of previously unknown documents were discovered in the archives of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Their number in the first months exceeded the entire volume collected over the past 35 years.”

Letters from the past: the struggle for a national state

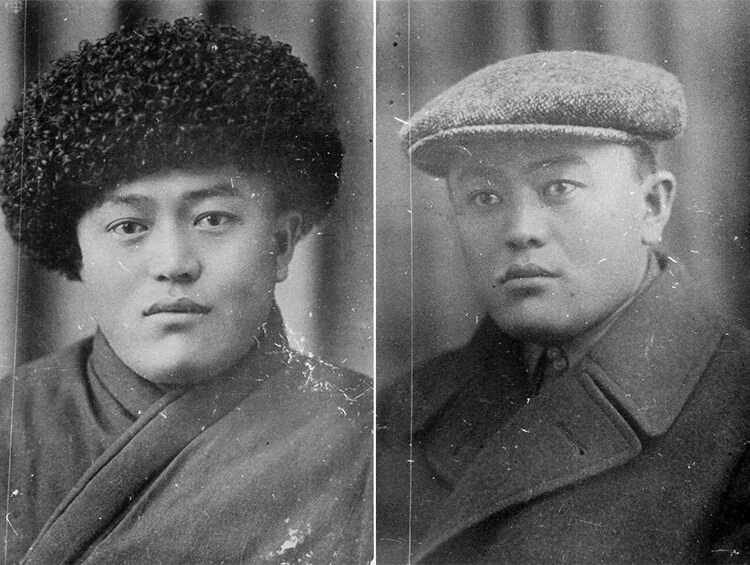

In the early 1920s, the Kyrgyz people faced the task of creating a state structure. To this end, Jusup Abdrakhmanov, together with Ishenaly Arabayev, Imanaly Aydarbekov, and Abdykerim Sydykov, initiated the creation of the Mountainous Kirghiz region. The founding congress took place on June 4, 1922, but soon all documents were annulled by order of Joseph Stalin.

Only in October 1924, after the division of the Turkestan ASSR, was the desired achieved — the Kara-Kirghiz Autonomous Region was formed within the RSFSR.

From that moment, amazing facts began to emerge.

One significant discovery was the fifth letter from Abdrakhmanov to Stalin, dated 1924, in which he justified the necessity of including the newly created Kirghiz Autonomous Region into the RSFSR.

“This was a strategically brilliant move,” Astemir explains. “It allowed for the strengthening of autonomy within a strong republic and continued the path to full sovereignty without confrontation, securing the support of the highest leadership of the USSR.”

The basis for such ambitious demands were impressive economic achievements. From 1927 to 1932, the Kirghiz ASSR, under the leadership of the 25-year-old Jusup Abdrakhmanov, demonstrated the highest growth rates among all the republics of the Union. This leadership allowed him to reasonably raise the issue of transforming autonomy into a union republic before the Politburo.

Topics for study

Founding Fathers of Modern Kyrgyzstan through the eyes of their descendants

“Analysis of the documents shows that in fact, Kyrgyzstan became a union republic as early as April 27, 1930,” Astemir adds. “On that day, a decision was made for Kyrgyzstan to enter into all relations with union bodies as a union republic. The legal formalization occurred in 1936.”

The name and its significance

Jusup Abdrakhmanov united his efforts with other Kyrgyz leaders. “He called Abdykerim Sydykov his teacher. When Abdykerim was expelled from the party, Jusup relied on Imanaly Aydarbekov and others,” notes Astemir.

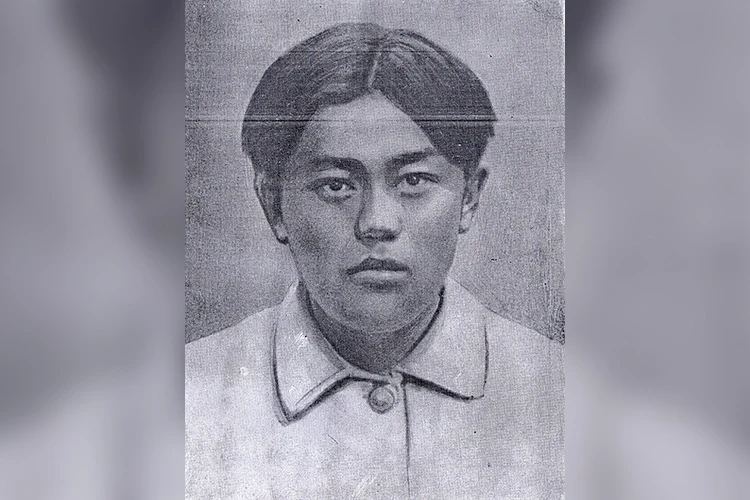

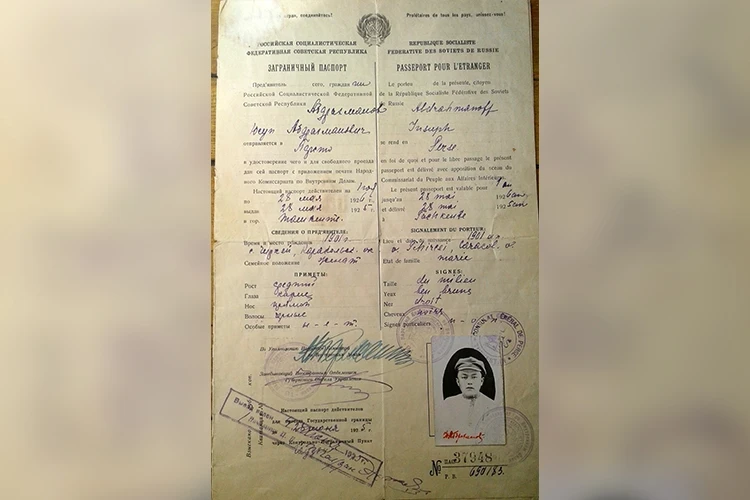

From 1920 to 1926, Jusup was actively engaged in political activities.

“In high state positions, at the age of 18, he participated in the III Congress of the Komsomol in Moscow, where he sat next to Vladimir Lenin and discussed important issues. Many believe he became the chairman of the Council of People's Commissars at 26, but in fact, he was only 25. Few know that he was also a member of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR. Even after he was declared an enemy of the people in 1933, he still formally remained a member of the presidium, although his political career effectively ended in 1931.

In his diary, Jusup wrote about himself: “Who am I? The son of a manap, a favorite of fate, a laborer, a Red Army soldier, the chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Kirghiz ASSR, a member of the presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR,” shares Astemir Abdrakhmanov.

The struggle for the railway: Kyrgyz TurkSib

Another important discovery is related to the struggle for the construction of the Turkestan-Siberian Railway. In the 1920s, Kyrgyzstan became one of the first on the path to industrialization, and Jusup Abdrakhmanov defended the decision to begin construction of the railway specifically from Frunze.

However, at the last moment, the leadership of TurkSib changed plans, proposing to route the railway around Kyrgyzstan. Abdrakhmanov entered into a decisive confrontation with high-ranking officials from the Soviet government.

“This unequal and difficult struggle lasted two months and attracted the attention of the international press,” Astemir recounts. “On November 3, 1927, Jusup secured from the Politburo the construction of a separate branch of the railway from Frunze deep into the country, to Issyk-Kul. The modern railway project from China to Kyrgyzstan to Uzbekistan is essentially the realization of his plan.”

Astemir dedicated a documentary film titled “The Iron Path of Jusup Abdrakhmanov — Kyrgyz TurkSib” to this story, which has already been nominated for the Toktogul Prize. He also plans to shoot a continuation of this topic.

Why did Pishpek (Frunze) become the capital of the republic?

“After the formation of the Kara-Kirghiz Autonomous Region, there was a threat to its territorial integrity. The management of the southern part of Kyrgyzstan was under the control of Tashkent, where the Central Asian leadership was located. In this regard, in 1924, Jusup proposed the immediate relocation of the government to Jalal-Abad for better organization of management,” explains Astemir.

But why did Frunze (Pishpek) remain the main capital of Kyrgyzstan?

By 1925, the leadership of the USSR began active steps towards industrialization. In 1926, while working in Moscow, Jusup and his associates achieved that the main construction project of the first five-year plan became the Turkestan-Siberian railway, with Frunze as its southern source. In 1925-1926, it no longer made sense to return to Jalal-Abad. Despite the fact that due to the shortsightedness of officials the railway passed 157 kilometers from Lugovoye, Frunze remained the logistical center and economic attraction of the republic, from where the journey to Issyk-Kul continued.

When the question of relocating the government became impossible, Jusup began to advocate for the idea of dividing the autonomy into 7 cantons: Frunze, Chui, Talas, Karakol, Naryn, Osh, Jalal-Abad.

It is important to note that the creation of the southern district was economically justified as early as 1924, but Jusup needed to buy time to strengthen the republic. Only at the end of October 1928, when the threat had somewhat subsided, did he initiate preparations for the creation of a separate southern district,” Astemir added.

Astemir also noted that Jusup actively promoted the sedentarization of the Kyrgyz people, understanding that this was necessary for the strengthening of the republic.

“In just one year, he managed to achieve the sedentarization of 8 thousand households. The following year, he sought help from the center for 30 thousand households, but his opponents were slow to respond. Nevertheless, Jusup continued his work in this direction,” Astemir added.

The man who stopped the famine

One of Abdrakhmanov's most significant feats was his struggle against famine in the 1930s. While other republics were struck by famine due to unrealistic grain procurement plans, he refused to surrender grain, saving not only his people but also more than a hundred thousand refugees from Kazakhstan.

In his diary, a bold dialogue with the leadership of the Central Asian Bureau of the VKP(b) is preserved:

Abdrakhmanov: “If you do not provide bread for our cotton pickers, you will not receive fodder from us.”

Leadership: “How is this possible? This is a violation of party discipline!”

Abdrakhmanov: “I understand. But cotton has union significance. I want to provide people with bread. If I lose my party card for this — so be it!”

As a result, he managed to “secure” 5 thousand centners of grain, saving thousands of lives.

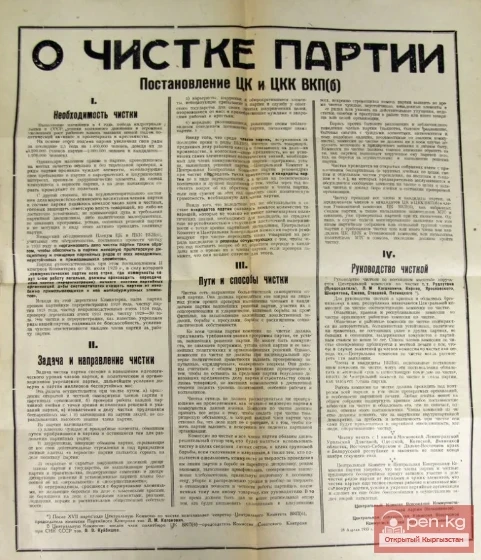

The diary as a sentence

The personal diary was the only confidant for Abdrakhmanov. “You are loyal to me while in my hands. But you can become a traitor in someone else's,” he wrote on the first page, foreseeing trouble.

And so it happened. The diary, in which he openly criticized the party line and Stalin, was stolen from his beloved Maria Natanson and ended up in the hands of the leader himself.

“Recently, I found in the Moscow archives a note from Stalin dated August 14, 1933, where he instructs Kaganovich and Molotov: ‘Read Abdrakhmanov's diary... It is clear that its author has been influenced by the Naumovs (Trotskyists). After reading, return it to me,’” shares Astemir.

Each member of the Politburo left their resolution on the diary, supporting Stalin. This effectively became his death sentence.

In September 1933, the Central Committee relieved Jusup of his position as chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Kirghiz ASSR. The case regarding his party affiliation was referred to the Central Control Commission of the VKP(b). He was accused of “failure to comply with party orders” and disrupting grain procurements. Where other local leaders followed Moscow's directives, leading their own people to famine, Kyrgyzstan, thanks to Jusup, avoided this tragedy.

On October 14, 1933, Jusup Abdrakhmanov was expelled from the party “for distorting party decisions,” but considering his previous activities, it was decided to revisit the question of his party membership in a year.

Abdrakhmanov was employed as deputy head of livestock management in Samara, and from 1935 he was transferred to a similar position in the Orenburg Oblast Executive Committee.

He wrote several letters to Stalin requesting reinstatement in the party, but all in vain. Jusup was arrested on April 4, 1937, on charges of anti-Soviet activities. He was transported from Orenburg to Frunze, where the investigation into his case continued.

The man behind the lines of history

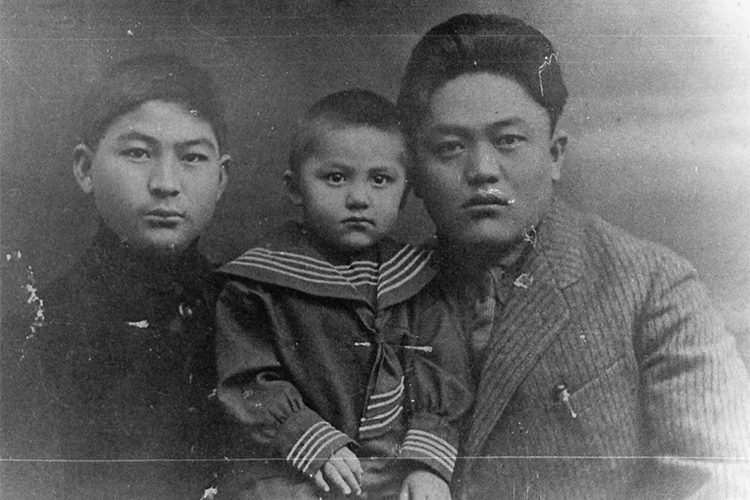

Who was Jusup in life? A strict but loving father of five children. A man of impeccable taste, who was friends with Vladimir Mayakovsky, receiving unexpected gifts from him — for example, a Gillette shaving set for himself and a gold watch for his wife Gulbakhram.

“In the inventory of confiscated property of Jusup, there is even a lady's Browning pistol that Mayakovsky gave him. These facts testify to the close friendship of my great-grandfather with the poet!” believes Astemir Abdrakhmanov.

By the way, there are archival photographs showing Jusup Abdrakhmanov carrying Mayakovsky's coffin, along with the poet's mother and sisters, Lilya and Osip Brik — they were among the closest people who accompanied the poet on his last journey.

The great-grandson first heard about his ancestor from his grandfather Alibek:

“I was seven years old. I came home from school and told him that a classmate's grandfather was a famous poet. To which my grandfather replied: ‘And you tell him that your great-grandfather is the first revolutionary.’ Then I imagined him tall and handsome in a white uniform with a pistol.”

Later, grandfather shared the truth — his father was illegally shot, and he tried to protect his children from this terrible history, as the stigma of “son of an enemy of the people” destroyed lives.

Descendants of Jusup Abdrakhmanov

It is known that Jusup Abdrakhmanov had five children. Astemir recounts that the eldest son Anvar, a front-line soldier, was seriously wounded and soon after returning home died. They say he resembled his father the most. The second son Alibek became a cultural figure and worked as the director of the philharmonic.

Daughter Aida graduated from studies in Leningrad and returned home in 1949, but she was denied work as the daughter of an enemy of the people. “In this country, you will not work!” — that’s what she was told. Eventually, Aida moved to Kazakhstan, where she worked on TurkSib, which her father promoted, and became an honorary railway worker.

Another daughter, Raisa, worked in the trade unions. The youngest daughter, Lenina, who was the chairwoman of the factory trade union committee "Ainur," spent her life fighting to restore her father's good name. She actively participated in excavations at Chon-Tash, where Jusup was identified by his golden teeth. It was she who appealed to the All-Union Party Conference and Mikhail Gorbachev requesting the rehabilitation of Jusup Abdrakhmanov. As a result, in 1958 he was rehabilitated in civil matters, and in party matters only in 1988,” noted Astemir Abdrakhmanov.

Astemir added that his family also faced the “stigma of shame.”

“My mother worked in the circus as an aerial gymnast, and one day an elderly man told her that he knew Jusup Abdrakhmanov and that he was an enemy of the people. At that time, my mother knew nothing about her grandfather, and this acknowledgment shocked her. She was unhappy that her grandfather did not tell her the truth. As a result, her father obtained two documents: one about Jusup's civil rehabilitation, the other — his appeal to the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR Nikolai Yezhov, in which he wrote that he was driven to an insane state during his arrest and his testimony against people he did not know could not be considered reliable. This document reached grandfather through an acquaintance,” reported Astemir Abdrakhmanov.

The great-grandson of the famous statesman also shared about himself: he graduated from the Polytechnic Institute but works in the tourism sector. He is currently actively studying the legacy of Abdrakhmanov.

Interrupted life

On the night of November 5-6, 1938, Jusup Abdrakhmanov was accused of belonging to an “anti-Soviet terrorist organization, whose goal was to overthrow the Soviet power and create a bourgeois nationalist state oriented towards England.”

He was sentenced to death, and the execution was carried out on the eve of the 21st anniversary of the October Revolution, to which he dedicated his life. At the time of his execution, he was only 36 years old.

Jusup's remains were found among 137 victims of Stalin's repressions in a mass grave in the village of Chon-Tash.

The return of the name

Today, work continues to restore historical justice. The government of Kyrgyzstan has set the task of nominating Jusup Abdrakhmanov's diaries for the UNESCO “Memory of the World” program.

One of the central streets of Bishkek is named after Jusup Abdrakhmanov, and the Academy of Public Administration under the President of the Kyrgyz Republic has been named in his honor.

Monuments to Jusup Abdrakhmanov have been erected throughout the country and beyond. In his native village of Jarkynbaev, a bust was installed in honor of the 100th anniversary of the figure's birth, and monuments have been opened in the cultural and ethnographic center "Rukh Ordo," as well as in the cities of Karakol and Cholpon-Ata.

In 2018, a memorial plaque was opened in Orenburg (Russia), and in 2021 a monument was erected in Ankara.

“It turns out to be a paradoxical situation,” concludes Astemir. “Abroad, interest in Abdrakhmanov has continued for over 30 years, with new documents about him being found. We are just beginning to uncover the true scale of his personality. And it is our duty to preserve this memory for future generations.”