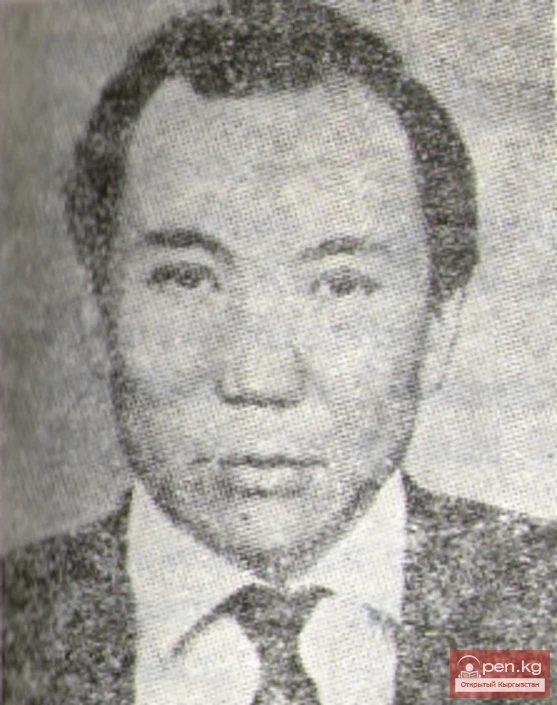

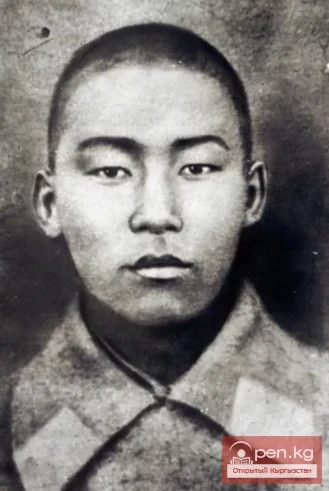

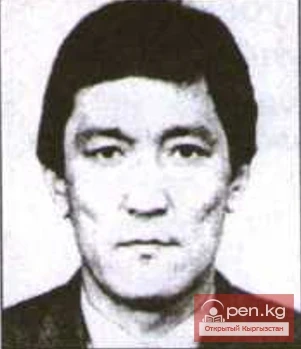

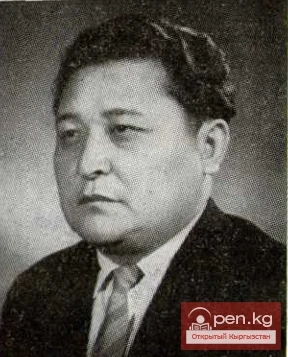

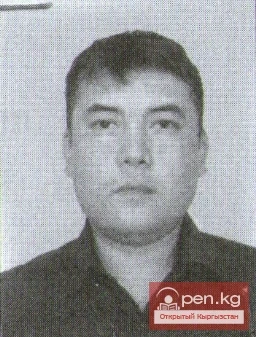

Hero of the Soviet Union Yakubov Osmon

Osmon Yakubov was born in 1911 in the village of Naiman, Khaldyvanbek district, Andijan region of the Uzbek SSR, in a teacher's family. In 1926, he moved with his parents to the village of Togua-Bulak in the Uzgen district of the Osh region of the Kyrgyz SSR. He was Kyrgyz and a Komsomol member. He actively participated in the organization of the collective farm "Kyzyl Oktyabr." At the call of the Komsomol, he worked on the construction of the Otuz-Adyr Canal in 1940-1941. He was drafted into the Soviet Army in December 1941. He served as a guard private and was a rifleman-automatic rifle shooter.

He began his combat path at the walls of Stalingrad. He then fought on many fronts. He was wounded twice but returned to duty each time.

While clearing the settlement of Orekhi in the Vitebsk region from the enemy, he fell in a hand-to-hand combat, dying a heroic death. The Soviet government highly appreciated his combat merits and the courage of this fearless warrior. On July 22, 1944, he was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

One of the streets in the village of Toguz-Bulak in the Uzgen district of the Osh region, a local secondary school, and a pioneer squad are named after the Hero.

NOBLE FURY

Soldiers' fates during the war varied greatly. Some had to endure it from the first day to the last, experiencing the burning bitterness of retreat, as dear fields and cities of Soviet land were left to the enemy, and the joy of an unstoppable, crushing offensive, as the fascist filth was swept from their native land.

Another soldier, however, barely had time to fight, as his life was cut short by the first enemy bullet he encountered or by the first random shell fragment... And how can one measure, how can one evaluate: was the soldier's path in the war long or short? And is this path evaluated only by time? Hardly. Most likely, it is measured by the fulfillment of a soldier's duty.

Less than a year remained until the immortal Victory Day of the Soviet people in the Great Patriotic War when guard private Osmon Yakubov fought his last battle. By that time, the thirty-three-year-old automatic rifle shooter of the first rifle battalion of the 201st guard regiment of the 67th rifle division of the 1st Baltic Front had two wounds, brief hospital breaks, a medal "For Courage," and a soldier's path from the walls of the glorified Stalingrad almost to the borders of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

In addition, Osmon Yakubov had 16 years of Komsomol experience, actively participated in the organization of the first collective farm "Kyzyl Oktyabr" in what is now the Uzgen district of the Osh region, and, at the call of the Lenin Komsomol, worked on the construction of one of the first irrigation canals in our mountainous republic, the Otuz-Adyr Canal...

We, the generation of Soviet people born after the victorious end of the Great Patriotic War, usually judge the events that preceded us based on numerous documentary and artistic books, films, old newspaper articles, and archival publications, as well as the stories of direct witnesses. And this judgment has formed in the overwhelming majority of our generation in a roughly similar way, though with varying degrees of natural imagination. Thus, these two brief pieces of information about Osmon Yakubov's active participation in the organization of the first collective farm "Kyzyl Oktyabr" in the district and his work on the construction of one of the first canals in the republic allow us to confidently sketch a rather comprehensive portrait of the person involved in those events. Especially since just recently, each of us witnessed the grand construction of the Baikal-Amur Mainline, witnessing unparalleled courage, organizational skills, and the ability to subordinate personal interests to the interests of society...

Now let us imagine a person who had to demonstrate all these qualities in the turbulent 20s and 30s in the south of our republic, when in the border areas and in remote mountain villages, the remnants of particularly brutal bandit groups were rampant; when not only walking excavators but even the first low-powered "Fordson" tractors were considered a curiosity, and the first collective farms were concerned about horses and carts to make better use of ordinary human strength and unprecedented enthusiasm. For they were finally establishing their own, native land. And thus, they defended it from the bandits, from the feudal lords and landowners with exceptional courage and fury, as one defends justice; and they loved it with special delight and tenderness, as a mother and father love their child.

All this was experienced by Komsomol member Osmon Yakubov while defending the collective farm's granary from bandit arson, dodging bullets fired from around the corner, digging into the parched Asian soil until his hands bled, so that he could water it sufficiently, so that it could finally reward free labor with a bountiful and much-desired harvest.

By the age of thirty-three, he had seen much and given a well-measured assessment shaped by blood and sweat. And that is why we consider the reasoning of some Western ideologists and Sovietologists about an alleged fanaticism of Soviet people during the Great Patriotic War to be the height of sacrilege. No, this is not fanaticism. "This is ordinary defense of one's own home, one's family, and finally, one's happiness from foreign encroachment. And it is quite easy for any unbiased observer to understand that for every Soviet person after the Great October Revolution, their home, their family became the entire country, the whole people...

These are the roots of the feat of Osmon Yakubov, as well as of all Soviet people during the sacred war against fascism, the roots of his noble fury with which he fought his last battle for the liberation of the Belarusian village of Orekhi.

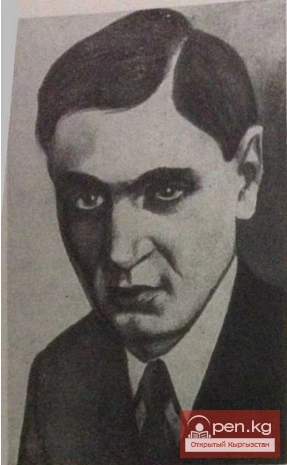

On that summer day, the 201st guard regiment of the 67th rifle division of the 1st Baltic Front received a combat mission to conduct reconnaissance by combat in the heavily fortified area of Sirotino-Orsha, Vitebsk region, and to launch an offensive.

No, this was not yet the beginning of Operation "Bagration," the implementation of which allowed Soviet troops to quickly clear the war-torn Belarus from fascist filth. In the memoirs of our greatest military leaders, G.K. Zhukov and A.M. Vasilevsky, these crushing attacks by Soviet soldiers are simply referred to as: on July 22-23, the Red Army conducted reconnaissance by combat, which clarified the quality and quantity of the enemy's defensive fortifications. Additionally, Georgy Konstantinovich expressed regret about the weather conditions at that time: drizzling rain and extremely low overcast clouds, which practically excluded the use of aviation by the Soviet command, whose advantage over the fascists was becoming increasingly significant by that time.

Thus, the main burden in the first stage of Operation "Bagration" fell on the shoulders of artillerymen, tankers, and, of course, primarily on the shoulders of the "queen of the fields" — the infantry.

Naturally, the ordinary soldiers were not privy to the intricacies and details of the grand operation that had begun. Nor could they be. They simply knew that their guard regiment, as part of the 67th rifle division, was to conduct reconnaissance by combat in the Sirotino-Orsha area. They also knew and believed that only a few days remained to finally reach the State border of the USSR.

Therefore, the overwhelming majority of the personnel of the 201st guard rifle regiment knew only one task — to capture the small Belarusian village of Orekhi from the enemy, to clear it of the enemy, and then there would be a new order, which, like the previous ones, must be executed unconditionally: whether at the cost of modern training, ingenuity, and fearlessness, or even at the cost of their own lives.

Guard private Yakubov was the first to storm the enemy trench during the reconnaissance by combat. When further advancement was halted by machine gun fire, Yakubov volunteered to destroy the firing point.

Don't rush...

Dolgov looked at one of his soldiers, and he quickly prepared a bundle of grenades. Osmon, understanding his commander without words, changed the magazine of his automatic rifle in the meantime. The platoon commander nodded to him towards a small depression that could provide some cover for the prone soldier.

—Don't rush... Dolgov repeated, "We need to act with certainty."

No one knows how long the distance seemed to guard private Osmon Yakubov

— Comrade commander, may I? — Osmon Yakubov threw a pleading glance at his platoon commander Dolgov, who was lying nearby.

The few dozen meters that separated him from the fascist pillbox, as he crawled towards it, hiding behind the smallest mounds and bumps, rolling into shallow ditches made by melting snow in spring. And he hardly measured that small distance separating life from death with such naked obviousness.

Having covered a few more meters, Osmon Yakubov stopped, caught his breath, and forced himself to calm down.

The deadly fire spewing embrasure was very close, and he wanted to finish off the pillbox as soon as possible. But Osmon understood: he must eliminate even one chance in a thousand that the fascist pillbox would continue firing at his comrades. "Don't rush," he repeated to himself the words of platoon commander Dolgov, leaned back slightly, tensed his body like a taut spring, swung widely, and sent the bundle of grenades into the fire-breathing black hole.

A deafening explosion shook the ground, the thick smoke seemed to absorb the machine gun fire from the enemy pillbox, momentarily bringing silence. But in the next moment, the half-stunned Osmon Yakubov was lifted from the ground by an avalanche of "Hurrah!" from his fellow soldiers, and he, along with them, rushed to continue the attack, pursuing the disorganized fleeing Germans and sparing only those who managed to turn towards the attackers and raise their hands unarmed.

Osmon Yakubov ran out of ammunition. But the fascists were only two or three steps away, aiming at him, not leaving a moment to catch his breath or change the magazine... Grabbing the rifle by the barrel, Osmon continued to smash the enemies, knocking off their hated steel helmets with the butt. And suddenly, it was as if he stumbled upon something hard, hot, tearing into his chest. He managed to take a few more steps forward, dragging his comrades into the last attack of his life...

...The secondary school "Kyzyl Oktyabr" in the Uzgen district of the Osh region is named after the Hero of the Soviet Union Osmon Yakubov. At the entrance to the building, in an enlarged portrait, stands forever the thirty-three-year-old soldier of the Soviet Army, one of those whose noble fury, boiling over like a wave, swept the fascist filth from our native land.

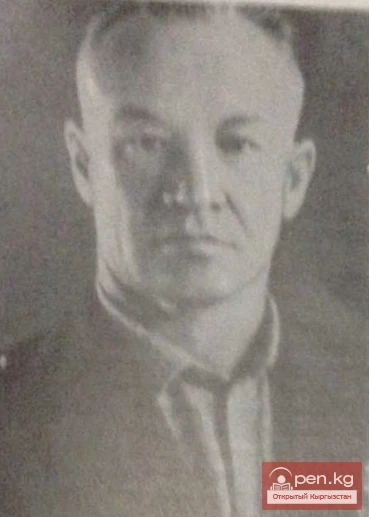

A. ALYANCHIKOV