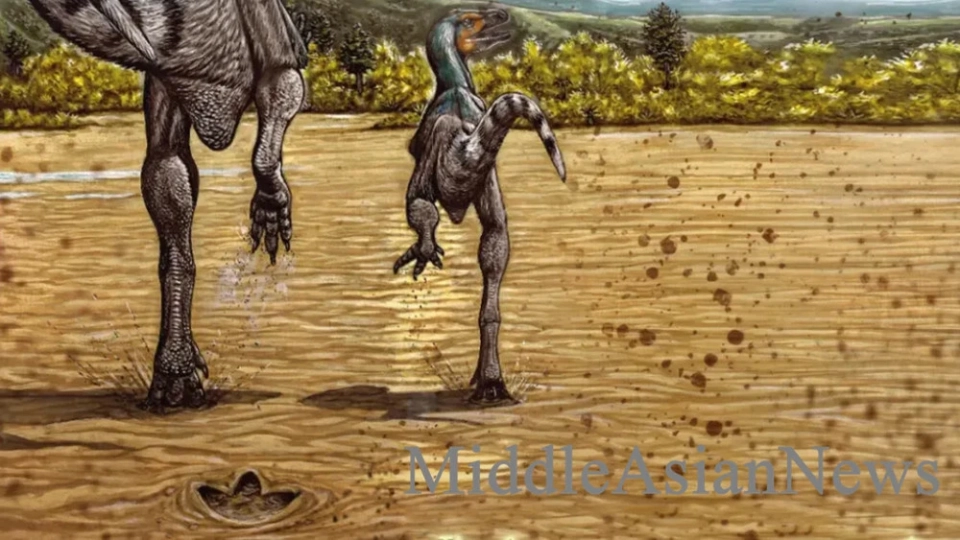

A recent paleontological discovery fundamentally changes our understanding of theropods. The analysis of ancient footprints suggests that one of the fastest dinosaurs may have lived during the Cretaceous period, raising new questions about the capabilities of predatory prehistoric creatures.

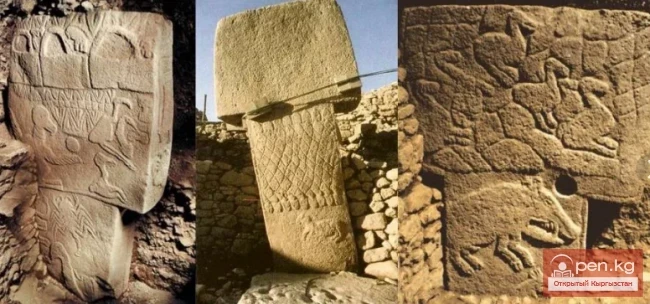

The footprints discovered in Mongolia, dating back 120 million years, shed new light on the movement patterns of theropods. According to the fossilized prints, they may belong to the fastest dinosaur ever discovered, capable of running at an astonishing speed—comparable to that of a modern professional cyclist, reports IFLScience.

What are the actual speeds of dinosaurs?

While dinosaurs are typically depicted as bulky and slow creatures, new findings radically change this perception. By examining footprints from the Cretaceous period, scientists have identified tracks likely belonging to the fastest theropod. This medium-sized predatory dinosaur is believed to have reached speeds of up to 45 kilometers per hour.

This level of speed is not only unique among dinosaurs but also comparable to modern standards, achieving rates characteristic of professional cyclists.

Footprints of the fastest dinosaur found in Mongolia

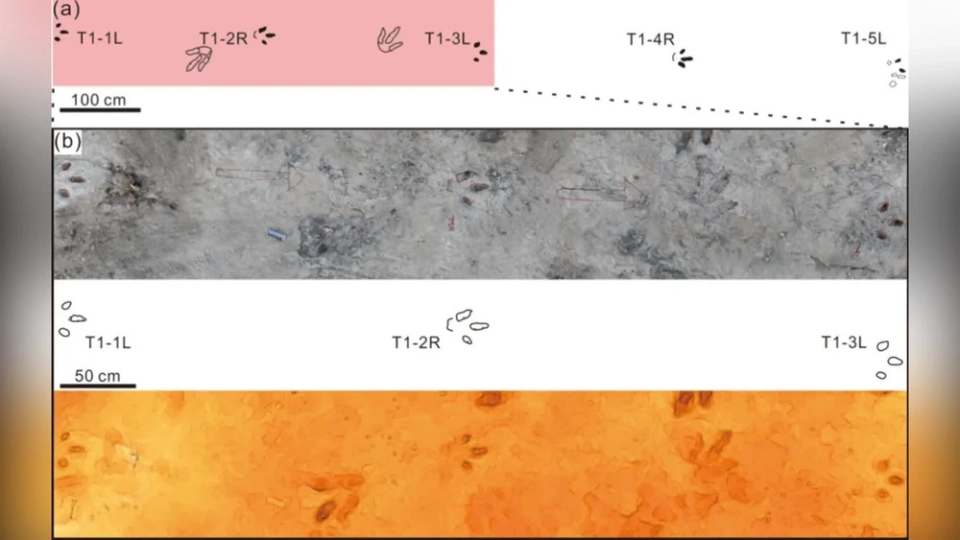

The footprints were discovered in a lower Cretaceous layer of sedimentary rock in Mongolia, indicating that their owners existed approximately 120–130 million years ago. It is particularly interesting that two different tracks were found at this site.

One of these tracks belongs to a large theropod, which, according to studies, is classified as the species Chapus lockleyi. This animal apparently moved at a steady, calm pace.

In contrast, the other track indicates more active movement: it was left by another yet unidentified animal belonging to the group Eubrontidae, and it may represent the footprint of the fastest dinosaur that ever lived on Earth.

Methods for calculating dinosaur speed

The study of fossilized footprints falls within the field of ichnology, which examines traces left by ancient creatures. To determine a dinosaur's speed, scientists first measure the size of the animal and the length of its stride, then compare these data with the estimated height of the hip.

Based on the relative length of the stride, researchers can distinguish between walking, trotting, and running.

The walking index is typically less than 2, while running speed begins above 2.9. For the theropod in question, this index turned out to be surprisingly high—5.25—indicating its sprinting capabilities.

The details of the footprints further confirm the conclusion of high speed. The tracks are particularly noticeable on the toes, while heel prints are almost absent—this is characteristic of fast, sharp running, observed in modern animals as well. Additionally, the footprints appear almost perfectly straight, indicating that the animal moved forward at maximum speed without maneuvering.

What does this discovery say about theropods?

This discovery supports previous biomechanical models suggesting that large theropods generally moved slower, while smaller and medium-sized predators could achieve exceptionally high speeds.

This discovery serves as compelling evidence that theoretical models are validated by real data obtained from fossilized footprints.

Tatar S. Maydar

source: MiddleAsianNew