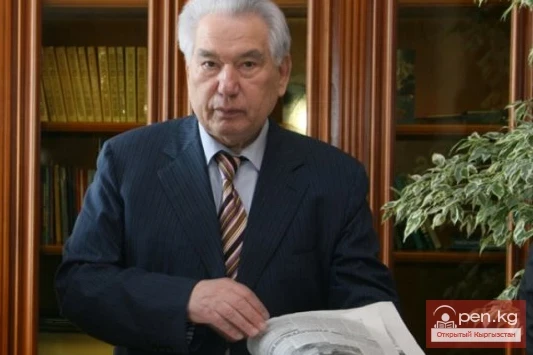

Criticism of Aitmatov's work may be permissible, but the problem lies not in that. The question is much deeper and concerns the very approach to evaluating literature.

"Haven't read it, but condemn it"

This well-known phrase, which emerged in the late 1950s during the persecution of Boris Pasternak after he received the Nobel Prize, has become a symbol of a superficial attitude toward art. It reflects confidence without proper knowledge and indicates ignorance.

Syimyk Zhapikeev openly admits that he has not read Aitmatov's works and is not interested in them, yet he boldly delivers his "verdict." While choosing not to read is everyone's right, condemning works about which one has no even elementary understanding is a manifestation of intellectual self-discredit.

When discussing Aitmatov's work, it should be understood that he is not just part of the school curriculum or a Kyrgyz cultural symbol. He is a philosopher-writer whose work is deeply woven into the global humanitarian tradition of the 20th century.

Chingiz Aitmatov is a figure representing an entire era, not just a matter of taste.

In Zhapikeev's view, literature should inspire and "give a push." However, Aitmatov is not a personal growth coach or a preacher. He did not set out to "sell success" or teach how to live. His aim is more complex themes, such as human nature, memory, violence, the meaning of life, and values.

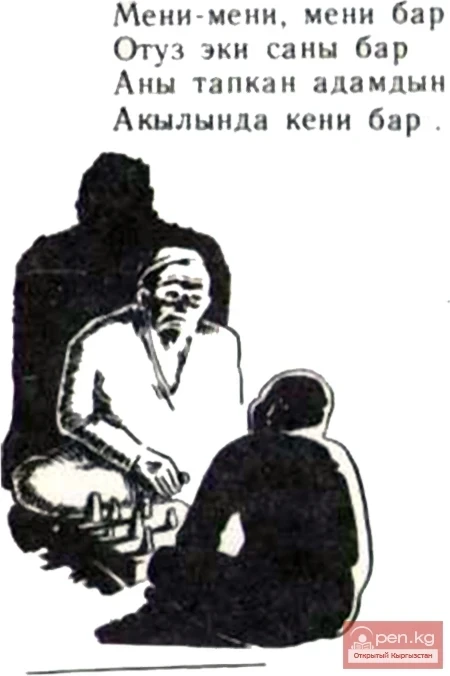

The concept of mankurtism is not just a plot but a metaphor of a civilizational level, warning that a society devoid of memory becomes manageable, easily destructible, and turns into a function.

Comparison with Bruce Lee

Syimyk Zhapikeev places Aitmatov on the same level as Bruce Lee. However, such a comparison only highlights the diagnosis of our time. This does not mean that Lee is less significant—he is a genius in his field, an icon of mass culture.

Comparing Aitmatov and Lee is inappropriate, as their approaches to art are different. Aitmatov creates a long internal dialogue, while Lee inspires action.

One encourages movement, while the other provokes thought. However, thinking is a more complex task, and it does not always provide an immediate "wow effect."

In today's world, where clip thinking and short attention spans prevail, deep thoughts are often lost against the backdrop of bright external effects.

Zhapikeev's judgments that Aitmatov "praised the Union" and fixed a person within the framework of their profession appear primitive. He did not discuss social lifts but raised questions of a person's internal responsibility, the dignity of labor, and the tragedy when the system deprives one of choice. These are entirely different topics. To distinguish them, one must read, not skim through works superficially.

Discussion of Zhapikeev's Statements

Zhapikeev's statements about Chingiz Aitmatov are not just his personal opinion. They reflect a symptom of the times when loudness replaces depth, and confidence substitutes competence.

No one forbids criticizing Aitmatov, and serious criticism indicates a vibrant culture. However, it is essential to distinguish between constructive criticism and a demonstrative refusal even to attempt to understand.

When a public figure says, "I haven't read it, I'm not interested," they are not challenging Aitmatov's work but merely setting the boundaries of their intellectual horizon. This causes public resonance, as Aitmatov serves as a kind of marker for the level of discussion. Refusing to reflect is a refusal to gain a deeper understanding of history and experience.

If culture is replaced by simple motivations, philosophy by instructions, and literature by "inspiring content," society becomes simplified.

A simplified society is easily managed, and mankurtism begins precisely with this.

Chingiz Aitmatov does not need protection—he has long outlived his critics. However, Kyrgyz society must be protected from the spread of intellectual mediocrity, which is often presented as honesty and freedom of opinion.