Zima Boris Mikhailovich – Honored Teacher and Honored Figure of Science of the Kyrgyz SSR

.Professor, who made a significant contribution to the development of higher education and the training of scientific and pedagogical personnel in the republic, as well as to the study of many issues in the history of Kyrgyzstan.

Studying at the Moscow Historical and Philosophical Institute was an important stage in his life. Here, the former worker and turner, a graduate of the labor faculty, mastered the basics of social sciences and gained deep historical knowledge.

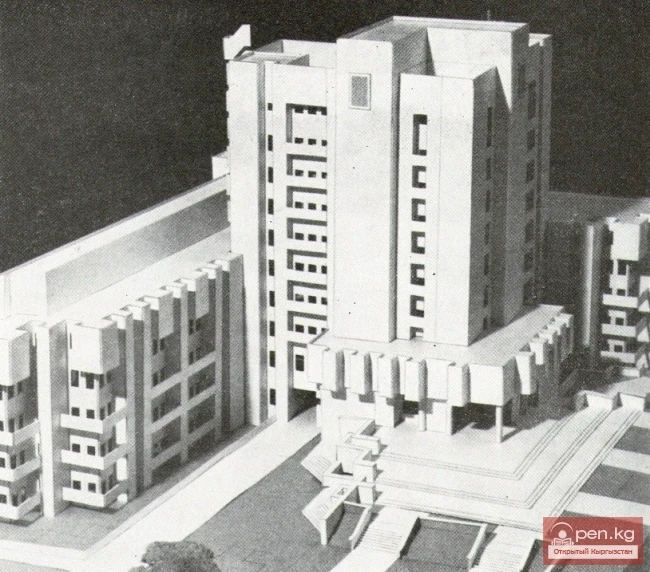

In 1935, even before defending his diploma, the People's Commissariat for Education of the RSFSR invited B.M. Zima to work as a teacher at one of the country's universities, where there was an acute shortage of teachers with higher education. He found himself once again, this time with his family, in Central Asia, at the Kyrgyz State Pedagogical Institute. Upon arriving in Frunze on April 1, 1935, Boris Mikhailovich and his wife Anna Gavrilovna were enrolled as assistants: he at the Department of General History, she at the Department of the History of the CPSU.

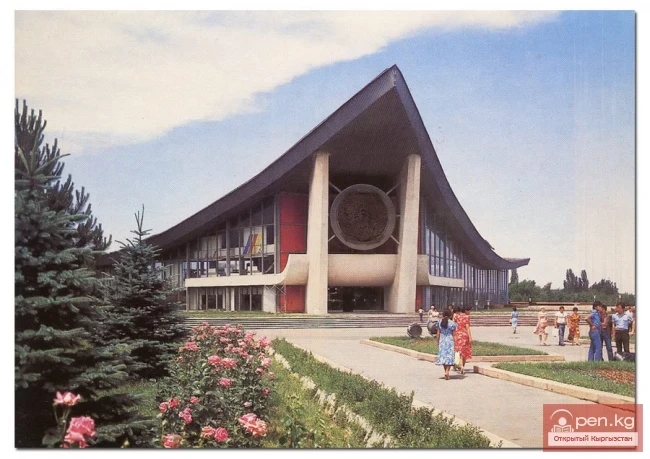

All of Boris Mikhailovich's labor and public activities are connected with this educational institution. At the Kyrgyz State Pedagogical Institute and the Kyrgyz State University established on its basis in 1951, B.M. Zima, alongside his teaching activities, performed scientific and administrative work as dean of the history faculty, head of the department, and deputy director for part-time education. However, his primary focus remained on pedagogical and scientific activities. Having received a diverse education at the Moscow Historical and Philosophical Institute, B.M. Zima delivered lectures and conducted practical classes on ancient, medieval, and modern history, as well as the history of the USSR.

In 1936, the Kyrgyz State Pedagogical Institute conducted its first graduation of specialists.

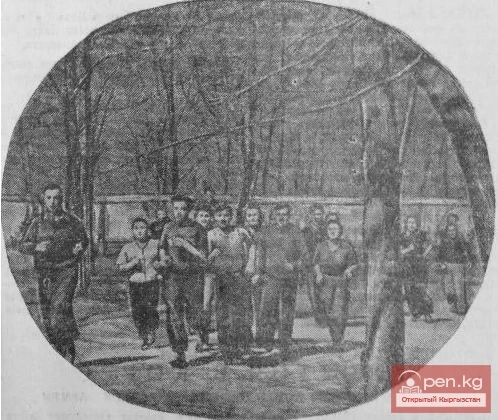

In the following year, 1937, under the initiative and leadership of B.M. Zima, the first historical and archaeological expedition was carried out, laying the foundation for archaeological research into the ancient and medieval history of Kyrgyzstan. Students from the history faculty actively participated in the expedition…

Boris Mikhailovich Zima was born on July 20, 1908, in Kirovograd – formerly Elisavetgrad, into a large Ukrainian working-class family. His father, Mikhail Akimovich, was a professional foundry worker and worked at the factory for about 50 years. Besides Boris, there were eight other children in the family. The large family barely made ends meet, so when the boy reached school age, he could not go to school. He learned to read and write with the help of his older brothers and sisters. Only in 1920, when Boris turned 12, did he start school, but after a year, he left and went to work. He became an apprentice foundry worker in a private workshop owned by an entrepreneur named Shabli in Elisavetgrad. Here’s how Boris Mikhailovich describes his “universities” in his “Autobiography”: “From that time (December 1921) until 1931, I studied and worked intermittently. By 1925, I had completed 5 grades of secondary school.

In 1925, I dropped out of school and went to work at the ‘Chugun-Litie’ factory, where I was an apprentice metal turner.

In February 1927, I began working independently as a metal turner. I worked as a turner until August 1931 (there was a break due to my studies at the labor faculty from February to July 1930).”

This is the simple yet difficult fate of the boy Boris Zima. It closely resembles the biographies of many children from working-class families who had to earn a living from a young age while striving for an education.

He himself wrote about this: “All the years from 1925 to 1931 (until I entered the Moscow Historical and Philosophical Institute) I studied in evening schools and preparatory courses for working youth while working at the factory. Thus, I prepared myself for admission to the third (final) year of the labor faculty. I was sent to the labor faculty by the Tashkent City Committee of the Komsomol. I graduated from the labor faculty in 1930.”

In his “Autobiography,” Boris Mikhailovich did not dwell on the geographical details of his life path during his youth. However, the “strict” personal record sheet indicates that in Kirovograd, he studied and worked as a metal turner at the ‘Chugun-Litie’ and ‘Smena’ factories until 1928, that is, until he was 20 years old. In September 1928, he worked in the same profession in the mechanical workshops of Tashkent. In 1930, he was a student at the labor faculty named after I.V. Stalin in Samarkand. From October 1930 to October 1931, Boris Zima worked as a metal turner at the Petrovsky factory in Kherson.

Thus, in three years, in search of work and education, Boris Zima visited four cities in Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

Finally, in 1931, he successfully passed the entrance exams and enrolled in the history faculty of the Historical and Philosophical Institute in Moscow.

In 1935, as Boris Mikhailovich himself reported in his “Autobiography”: “I was sent by the People's Commissariat of the RSFSR to work in the city of Frunze at the Kyrgyz State Pedagogical Institute as a history teacher.

There I worked first as an ordinary teacher, and then, alongside this, I fulfilled the duties of dean of the history faculty, head of the department of ancient history and the Middle Ages, and deputy director for part-time education (I performed all these duties not simultaneously, but at different times).”

The first expedition of the pedagogical institute in 1937, led by B.M. Zima, surveyed historical and cultural monuments over a large part of Kyrgyzstan. Reports on the results of its work could be read in the newspaper “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” (July 28, 1937) in his article “Historical and Archaeological Expedition of the Committee of Sciences under the Council of Ministers of the Kyrgyz SSR.” In the autumn of the same year, B.M. Zima published an article in the newspaper “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” titled “Historical and Archaeological Expeditions in Kyrgyzstan.”

The expedition worked in various regions of the republic. In particular, in the Naryn region, the participants focused on studying the Tash-Rabat monument. In October 1937, the public of the republic could read B.M. Zima's article “Monuments of Antiquity. Tash-Rabat” in the newspaper “Soviet Kyrgyzstan.”

The expedition studied the settlements of Koshoy-Kurgan and identified several burial mounds in the basins of the Kara-Koyun, At-Bashi, and Naryn rivers.

In the Issyk-Kul basin, monuments of nomadic and settled agricultural populations were examined in areas from the city of Cholpon-Ata to the village of Tyup and from the city of Przhevalsk to the Ton Valley. Near the village of Semenovka, the site of the discovery of objects from a Saka sacrificial complex, which were accidentally found by local residents, was surveyed. In 1941, B.M. Zima published a work titled “Issyk-Kul Altars.”

The results of the finds in the Ak-Ulen area – rock carvings and medieval inscriptions – were described by Boris Mikhailovich in the newspaper “Komsomolets of Kyrgyzstan” (April 18, 1941) in the article “Kyrgyzstan in Ancient and Medieval Periods.” An interesting complex of works was carried out in the Tyup Bay area.

In the Chui Valley, special attention was paid to surveying the settlements of Burana, Ak-Beshim, Krasnaya Rechka, Sokuluk, Belovodskoye, and Shish-Tyube. Stone sculptures – monuments of the Turks were delivered to the capital of the republic, the city of Frunze. However… particularly large volumes of work were carried out by the members of the expedition in documenting the burial mounds of the Saka-Usun period of Kyrgyzstan's history. The burial mounds discovered along the route from the city of Frunze to the village of Chaldovar were included on the “archaeological map.”

In the Talas Valley, the mausoleum of Manas was thoroughly studied: comprehensive photo documentation, measurements were taken, and information was collected from the local population. After the first excavations inside the mausoleum, three burials were discovered.

Here, in the Talas region, along the routes from Kirovskoye village to Talas city, mausoleums from the 18th–19th centuries were documented. On a huge rock in the Kulan-Sai area, inscriptions carved into the rock were discovered and photographed, arranged in 18 vertical lines. In the same Kulan-Sai area, as well as in the Chiyim-Tash gorge, clusters of rock paintings were discovered and documented.

In the Talas River valley, the settlements of Sadyr-Kurgan, Ak-Tyube II (near the village of Orlovka), Ak-Tyube I (near the city of Talas), and in the Kumyshtat area were studied. In the basin of the Ur-Maaral River, traces of an ancient irrigation network were discovered. These findings were reported in the publication by V. Borzukov “Historical and Archaeological Office of the Pedagogical Institute” in the newspaper “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” on December 14, 1937.

In the Osh region, expedition participants primarily studied the history of the cities of Osh and Uzgen, as well as the settlement near the village of Mady.

The pedagogical institute's expedition was the first to survey historical and cultural monuments over a large part of the republic. It had an exploratory nature, but the results of its research already represented significant scientific interest.

The materials collected by the expedition laid the foundation for the establishment of a historical and archaeological office at the Kyrgyz Pedagogical Institute. Subsequently, the exhibits of the office enriched the collections of the national culture museum of the republic, and a number of the most unique finds, including the Issyk-Kul altars, were donated to the State Hermitage in Leningrad.

The results of the expedition's work were highly appreciated by research institutions and individual scholars. In particular, the leading archaeology specialist A.N. Bernsham noted: “In 1937, the history department of the Kyrgyz Pedagogical Institute conducted a survey of a significant part of Kyrgyzstan – both Southern and Northern, managing to collect very interesting materials from a historical perspective. Among the collected materials, the random finds of bronze items (altars, lamps, cauldrons) from the Saka period are of particular significance; collections from the medieval period were gathered. The photographs of the historical monuments of Kyrgyzstan have great scientific value.”

It should be noted that in the recently published first part of the trilogy “History of Central Asia,” Y.N. Rerikh refers to the works of A.N. Bernsham as a source when discussing the hypothesis of the settlement of proto-Indo-Aryans. Among them is “Archaeological Essay on Northern Kyrgyzstan.”

B.M. Zima continued his archaeological research until the Great Patriotic War. In 1938–1941, he actively participated in expeditions organized by the Committee of Sciences under the Council of Ministers of the Kyrgyz SSR and the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, together with other faculty members and students from the history department. At the pedagogical institute, Boris Mikhailovich organized a student archaeological circle and successfully led its work for many years.

In 1938, B.M. Zima, along with students interested in archaeology, surveyed the site of the Sokuluk treasure of archaeological artifacts dating back to the Bronze Age. Thanks to Boris Mikhailovich's efforts, this unique find was preserved for science. Later, after ten years, these items from the treasure received a thorough scientific review in his article “The Hearth of Andronovo Culture in Northern Kyrgyzstan,” published in the Proceedings of the Institute of Language, Literature, and History of the Kyrgyz Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences (Vol. II. – 1948. – pp. 113–127).

The Great Patriotic War interrupted B.M. Zima's pedagogical and scientific activities. In January 1942, he was drafted into the active army and remained in the field until Victory.

In the personal record sheet filled out on December 23, 1949, B.M. Zima noted: “Participated in battles against the German invaders in the Great Patriotic War on the fronts: Voronezh from 8/VII–13/X–1942; Southwestern from 16/XII.42 – 28/II.43; 3rd Baltic from 22/VI.44 – February 1945; 1st Ukrainian from 20/II–8/V.1945.

In the column: has he been wounded, it is noted: three wounds: 1. On the Voronezh front on 20/VII.1942 – in the arm. 2. On the 3rd Baltic – 24/VI.1944 – in the head. 3. On the 3rd Baltic front on 17/IX.44 – in the abdomen.

But let’s return to his autobiography. B.M. Zima writes: “From 1/III–17/IX.1943, I participated in battles against the German invaders in the Pavlograd-Slavgorod area, and together with my unit, I was surrounded. As a result of our unit being dispersed by the enemy in the village of Chernoglazovo, I hid from 1/III–17/IX.43 in the territory temporarily occupied by the Germans. While hiding in the occupied territory, I preserved all military and party documents, weapons, and military uniforms. After breaking out of the encirclement, I served again in the ranks of the Soviet Army, participating in battles multiple times and being wounded twice.”

In both the personal record sheet and the autobiography, Boris Mikhailovich writes: “I received a reprimand from the party committee at the Political Administration of the Armed Forces of the USSR. The party reprimand (a severe reprimand with a notation in my personal file) was imposed on me for my untimely exit from the encirclement.” Boris Mikhailovich lived with this “party reprimand” all his life and did not like to tell us, his students, about it, even when we were already colleagues.

Boris Mikhailovich often shared interesting stories about the war, often with humor, but mainly about the events that took place during the liberation of European countries from the fascists. One episode that stood out was when he recounted: “Czechoslovakia – a large village – in the square in front of the administration, a group of local men is loudly and energetically discussing future plans and… using profanity in Russian.

I approached and asked: ‘Hey, guys, why are you swearing so loudly?’ They grinned and replied: ‘A strong Russian word helps!’”

We, students of the history faculty, knew almost nothing about Boris Mikhailovich's military service, that he completed his service in the army in March 1946 in Hungary, and that for his combat merits in the fight against fascist invaders, he was awarded the Order of the Red Star, medals for “Combat Merits,” “For the Liberation of Prague,” “For Victory over Germany” … And only on Victory Day, May 9, did we suddenly see the signs of his military achievements on his chest.

After returning from the army, B.M. Zima became one of the leading professors of the faculty, dedicating all his strength and knowledge to pedagogical activities and continuing scientific research.

In 1946, B.M. Zima again led an archaeological expedition of the Kyrgyz State Pedagogical Institute to study rock carvings in the Saymaly-Tash area – a remarkable reserve of the ancient visual art of Kyrgyzstan.

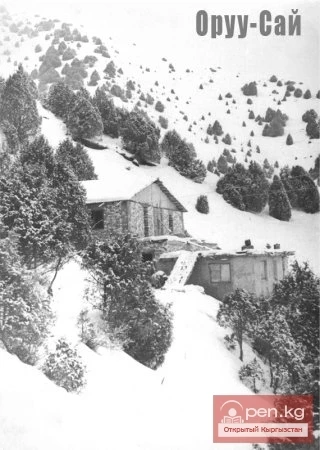

Saymaly-Tash is the oldest and most unique corner on Earth. Here’s how Leonid Dyadyuchenko “sings” of it: “Just as the paths snake, connecting once the mountain pastures of highland pastures with the agricultural oases of the Amu and Syr Darya, the ancient Oxus and Jaxartes. So high is Saymaly-Tash above the world, so low do the clouds that run from west to east drag over the mountain ridge day after day and century after century, that it is impossible to imagine Saymaly-Tash without this persistent motif of running cloud shadows, the running of time, and the constant roar of pre-mountain winds in the surrounding basalt rocks” (3).

In Kyrgyz, Saymaly-Tash means “patterned, embroidered stone.” Thus, the local population emphasized the uniqueness of Saymaly-Tash with its very name, distinguishing it from all other locations of ancient petroglyphs, and therefore, the place of development of the very creator of these petroglyphs. They are usually referred to here as “surot-tash,” “tamgaluu-tash,” that is, stone marked with a drawing or sign – tamga.

“Saymaly-Tash is a chapel, the Sistine of the Tian Shan, the highest achievement of that era, the Bronze Age” (4), exclaims the God-given writer, a geologist by education – Leonid Dyadyuchenko.

The history of the discovery of this rock gallery is not marked by any plot intrigue. Since time immemorial, shepherds, hunters, and indigenous residents of ails and kishlaks knew and spoke of it. Rumors about the shamanic “mountain Kogard” reached even St. Petersburg, the Russian Geographical Society, and P.P. Semenov in the 1870s, who was not yet known as Tien-Shan. In the summer of 1902, near the Kugart Pass, during surveys for the future postal road, topographer P.G. Khlyudov – a well-known artist and local historian in Turkestan – discovered an abundance of images of people and animals carved on stones. After that, members of the Turkestan Circle of Archaeology Lovers learned about this rock gallery.

However, neither in the early 20th century nor later in Turkestan, nor in Russia, was there any scientific development of the problems of the evolution of Stone Age art, and not only Stone Age art. In the book “Essays on Primitive Art,” A.A. Formozov wrote: “Articles on Stone Age art, inevitably touching on the question of the religion and ideology of the earliest humans, were then a convenient target for unscrupulous critics who accused the authors of these articles of clericalism, idealism, Marxism, etc.”

B.M. Zima thus became the first professional researcher of Saymaly-Tash. “In the articles he later wrote, the first researcher of Saymaly-Tash expressed the idea that the abundance and diversity of petroglyphs in this complex cover such a long period of time that it encompasses an entire stage in the development of the ancient inhabitants of these places. Thus, in the hunting scenes, he saw a progressive movement from the simplest forms of hunting to such sophisticated techniques as dog hunting, horseback pursuit, the construction of traps, enclosures, and the use of bows, lassos, slings, traps, and other hunting gear that are now unknown to us, and the depiction of which we may sometimes take for some magical signs and solar symbols.

In its development, hunting themes are often intertwined with themes of domesticating animals, breeding them, that is, the emergence of pastoralism. The abundance of these images, their concentration in one place, and the large temporal range lead the historian to conclude that the mountains of Central Asia, including Kyrgyzstan, were one of the centers of animal domestication and the development of pastoralism.”

The expedition conducted photography and stamping of the drawings, as well as their classification. In total, several thousand images were identified in the area, providing insight into many aspects of the life and activities of the ancient population of Kyrgyzstan.

The scientific inquiries of B.M. Zima were reflected in his publications: “Saymaly-Tash Rock Monuments” (“Soviet Kyrgyzstan,” 1946, October 27); “On the Origin of Rock Images” (Proceedings of KGPИ. – Frunze, 1948. – Vol. II. – Issue 2); “Some Conclusions on the Study of Rock Images in Kyrgyzstan” (Proceedings of KGPИ. Historical Series. – Frunze, 1950. – Issue 2); “From the History of the Study of Rock Images in Kyrgyzstan” (Proceedings of the Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz SSR. – Frunze, 1958. – Issue IV).

The materials from the studies of rock images in the Saymaly-Tash area formed the basis for B.M. Zima's candidate dissertation, which was successfully defended in 1948.

The expeditions led by him and the scientific publications of the 1940s and 1950s played an important role in the establishment of Kyrgyz archaeology as a science. He was a pioneer in discovering fascinating monuments of the Bronze Age, early nomads, and rock visual art. His publications on these topics have not lost their scientific significance to this day, although subsequent research has allowed for the clarification of some positions he expressed based on the relatively limited material available to science at that time.

This primarily concerns the exaggeration of the influence of Achaemenid Iran on the culture of Semirechye in the 6th–5th centuries BC and the attribution of the Issyk-Kul altars as material evidence of the Zoroastrian faith among the Saka tribes. On this issue, B.M. Zima prepared a work titled “Issyk-Kul Altars,” published in 1941. Later, new research by scholars led to the assumption that the worldview of the Saka contained only “elements of Zoroastrianism.”

The altars described by B.M. Zima, as well as those newly discovered by other scholars near the village of Chelpek, the city of Przhevalsk, and in the Tian Shan region, are associated with the ancient cult of the Sun and fire in its various manifestations. How this cult was related to Zoroastrianism remains indeterminate even today.

New data obtained from the study of a large number of monuments of Andronovo culture have allowed for the clarification of the date of the Sokuluk treasure proposed by B.M. Zima. While he believed that the treasure represented a complex of tools from the early stage of the Bronze Age, today all researchers unanimously attribute it to a later stage.

B.M. Zima's articles on the study of rock paintings in Kyrgyzstan have retained their scientific significance. It should be noted that subsequent studies using methods of mathematical statistics have expanded knowledge about them and provided new observations and conclusions.

Thus, despite new materials on the ancient history of Kyrgyzstan, B.M. Zima's overview works, as well as his articles on specific problems of archaeology, remain a necessary aid for all those studying the past of our republic in historiographical and scientific terms.

The contribution of B.M. Zima to the training of pedagogical and scientific personnel and to the development of historical education in the republic is immeasurable.

His school of lecturers, seminar leaders, and supervisors of diploma and dissertation works has trained hundreds of historians. In his lectures, devoid of external embellishments, a vibrant world of scientific knowledge opened up. Trust in the inquisitiveness of students and faith in their creative potential elicited a fruitful response. He always felt an organic need to pass on his vast knowledge, nurturing new generations of historians. He prepared a whole school of researchers who work in scientific institutions and educational establishments of the republic. His contributions to the training of national historian personnel are particularly significant.

Boris Mikhailovich had a knack for engaging his students with interesting, underexplored topics. I was fortunate to write my diploma thesis under the “watchful eye” of the Teacher. The topic we chose was generally unstudied, and even today, few are interested in it: “The Return and Settlement of Kyrgyz Refugees from China.” There was almost no literature, except for D. Furmanov's “Revolt.” I had to extract almost all materials literally from archives – our State archive, and also during archival practice – the Kazakh one in Almaty. And this was beneficial: the diploma was defended, and I am now forever devoted to history.

B.M. Zima devoted much energy and time to scientific organizational work. Showing constant attention to the problems of scientific development and the education of new generations of historian scholars, as well as to issues of historical education, Boris Mikhailovich developed a lecture course on the historiography of the history of Kyrgyzstan, headed the work on compiling programs on the history of the Kyrgyz SSR for the university and for secondary schools.

He also conducted extensive scientific and editorial work. The 13 volumes of “Proceedings of the History Faculty” that were published are the fruit of the tireless efforts and broad scientific outlook of B.M. Zima, who consistently provided immense assistance to young scholars of the faculty working in various fields of historical science.

Boris Mikhailovich Zima was always at the heart of public life. He was repeatedly elected a member of the party committee of Kyrgyz State University, headed the methodological commission, led the scientific student society, was the organizer and participant of many interesting events at the faculty, and actively engaged in the promotion of historical knowledge.

His broad erudition, remarkable personal qualities, and deep and constant interest in the development of science and the training of historians earned him the respect and love not only of numerous students but also of all those who knew him personally and benefited from his help and support.

A scholar, a widely known educator, a mentor to many generations of researchers, a patriot and promoter of science, B.M. Zima made a tremendous contribution to its development.

He was one of the initiators of the creation of the monograph “History of the Kyrgyz SSR.” Work on this effort began back in the late 1940s. In the early 1950s, a draft of “Essays on the History of the Kyrgyz SSR” Part I (from ancient times to 1917) was prepared. B.M. Zima was the author of the preface and editor of this volume.

From 1956 to 1968, three editions of “History of the Kyrgyz SSR” were published. This collective work covers the history of the Kyrgyz people from ancient times to the present day.

A significant part of Professor B.M. Zima's research focuses on the history of the Communist Party. He is a member of the author team for the first and second editions of “Essays on the History of the Communist Party of Kyrgyzstan” (1966, 1979).

Professor B.M. Zima's work on the history of Kyrgyzstan and its party organizations in 1937–1941 represents a substantial contribution to historiography.

Significant attention in Professor B.M. Zima's works is devoted to analyzing the process of establishing and improving higher education, as well as creating scientific personnel in Kyrgyzstan. These issues were examined in light of the epochal problems of the development of the economy and culture of the Kyrgyz people. As is known, the realization of these tasks in Kyrgyzstan was fraught with a number of additional difficulties. A qualitative leap was required from patriarchal-feudal relations and widespread illiteracy to the heights of science.

The paths and forms of its specific implementation are reflected in B.M. Zima's research.

Professor B.M. Zima is one of the leading specialists in the study of historiography problems. A brief retrospective overview of his scientific legacy shows how broad the range of his research in this area is. Analyzing his works, which predominantly have an essayistic character, one can notice that the object of study was not only individual aspects of the historiography of Kyrgyzstan but also the generalization of an entire stage in the formation and development of historical science in the republic. The diversity of themes is successfully combined with the breadth of the chronological framework of the research. The bibliography of Professor B.M. Zima's works is not limited to purely scientific research. His creative inquiries can also include studies and scientifically propagandistic works: the development of lecture and program-methodological materials for students. The positivity of such research is primarily determined by the combination of their scientific-research character with propagandistic and pedagogical orientation.

A notable place in the scientific and pedagogical activity of B.M. Zima is occupied by the course he developed on “Historiography of the History of Kyrgyzstan.”

As one of the leading historian specialists, B.M. Zima frequently contributed reviews of newly published works on the history of Kyrgyzstan to journals and newspapers. Knowledge of the scientific material, principledness, and kindness were the main criteria for his approach to any scientific publication.

Being a well-rounded educator and scholar, B.M. Zima actively engaged in propagandistic work, publishing articles in both Russian and Kyrgyz languages in periodicals, and giving reports and presentations at republican and all-union scientific conferences.

It should be noted that immediately after participating in the I All-Union Conference on Higher Education in May 1938 in Moscow, B.M. Zima initiated work with students from the history faculty to study the ancient monuments of Kyrgyzstan. A significant result of this was the conference of historians he organized in May 1941, which summarized the first scientific inquiries of the history faculty.

In February 1960, B.M. Zima participated in an inter-university scientific conference in Voronezh, dedicated to the problems of historiography of domestic and universal history, where he presented a report titled “Historical Science in Kyrgyzstan after the XX Congress of the CPSU.”

In May 1972, he participated in a All-Union scientific conference in Kyiv, dedicated to summarizing the experience of writing the history of cities and villages, factories and plants, collective farms and state farms of the USSR.

At the invitation of the Ministry of Higher and Secondary Specialized Education of the USSR, B.M. Zima participated in the All-Union meeting of higher education workers in January 1973.

In November 1977, in Moscow, B.M. Zima participated in the international scientific-theoretical conference “The Great October and the Modern Era.”

For his contributions to scientific and pedagogical work and youth education, B.M. Zima was awarded the Orders of Lenin, “Badge of Honor,” and the medal “For Valorous Labor.” In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of V.I. Lenin's birth, he received the title of “Excellence in National Education.” Recognition of B.M. Zima's significant contributions to the training of teaching staff in the republic was the awarding of the title “Honored Teacher of the Kyrgyz SSR” and in the field of science – “Honored Figure of Science of the Kyrgyz SSR.” B.M. Zima's many years of work were acknowledged with certificates of honor from the Ministry of Higher and Secondary Specialized Education of the USSR, the Ministry of National Education of the Kyrgyz SSR, the Republican Committee of Trade Unions, and others.

The entire year of 1979 was filled with extensive pedagogical and scientific work. In December 1979, Boris Mikhailovich passed away suddenly.

“…He never thought of himself. And at home, he was always worried about me and cared a lot…” – Anna Gavrilovna told us, mourning her faithful life partner, on that sad day.

In 1982, a posthumous publication of the works of Professor Boris Mikhailovich Zima from Kyrgyz State University on various but always relevant problems of studying the historical past of the republic was released. Instead of a preface, there is an “Outline of the Life and Activities of Professor B.M. Zima,” written by his grateful student – Doctor of Historical Sciences V.M. Ploskikh. Together with a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of Kyrgyzstan, Boris Mikhailovich's wife Anna Gavrilovna, and corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences K.K. Orozaliev, he prepared “Selected Scientific Works on the History of the Communist Party of Kyrgyzstan and the History of the Kyrgyz SSR.”

In our family library, we keep these “Selected Works” with an autograph: “Dear Vladimir Mikhailovich, this book is a memory of Boris Mikhailovich, who Loved You. Anna Gavrilovna.”

In honoring Professor B.M. Zima, who devoted all his knowledge and strength to the prosperity of Kyrgyzstan, an enthusiast for the development of public education and science in the republic, the Kyrgyz people immortalized his memory: a memorial plaque has been placed on the house where Boris Mikhailovich and Anna Gavrilovna lived; one of the streets in Bishkek is named after them, and the office at the history faculty of Kyrgyz State University and school No. 2 in Bishkek bear the name of B.M. Zima. The scientific works of Professor B.M. Zima continue to occupy a worthy place in the historical science of Kyrgyzstan.

… I don’t know why, but today I find myself increasingly recalling the last meetings with Boris Mikhailovich. They took place at the dacha, in the company of our family, with our children Vasya and Sveta always nearby. Perhaps it is nostalgia for something very dear that has passed. Today we ourselves have approached the age at which our Teacher was then…

He had a habit of getting off the bus at a brief “stop” at the water intake (or fast flow, as some dacha owners called it), about 3 km before the academic dachas. And then, leisurely crossing the fast mountain river on a bridge, he would “stroll,” as Boris Mikhailovich himself said, along the mountains from which the sun rose…

What was he thinking about, admiring the wonderful beauty of the nature of his second homeland, with which he linked his entire life? About the homeland where he and Anna Gavrilovna worked together in the field of education and science; where their children – Misha and Olya – were born and grew up; where he nurtured many devoted scholars of Mother History… Perhaps!

But… it is quite understandable, if we remember our Teacher as a Person, that these could have been hours of ordinary communication with the mountains, where through the grass on the stones, he saw the rock “writings” of our ancestors. Perhaps, noticing the long-dried riverbed of an ancient river, amidst the noise of the bubbling nearby Alamidin River, he thought about the distant gray times. The main thing is that all this was illuminated and warmed by the rising sun. And around – peace and silence…

The path to Professor Zima's dacha passed along the common road that also led to ours; one just needed to turn aside and walk about 50 meters. At his age, nearing seventy, it was probably not easy to walk almost three kilometers. At our dacha, he would take a “rest” – as Boris Mikhailovich joked.

It was morning, quite early, I was busy with household chores, and suddenly I heard: “Good morning!” I ran out, greeted him joyfully, and he asked: “Valyunechka, where is your other half?” – referring to Vladimir Mikhailovich, who was already graying, also a professor… And so it was every Sunday. And if, for some reason, Boris Mikhailovich did not appear one morning, we would worry, and most importantly – there was a feeling that something very important was missing.

After mutual greetings, the two professors would sit at a table in the garden, and I would join them with the children. Then there would be a light “dacha” breakfast and conversations, our questions and his always cheerful answers, transitioning into interesting stories about youth, the past, a little about the war, but mainly – simply about human life. Time “flew” by unnoticed, just as unnoticed as the “approaching” very venerable age has come to us now…

Once, I thought he looked more tired, not as cheerful as usual. I asked: “Boris Mikhailovich, are you feeling unwell?” He waved his hand and replied: “A little!”

And then, suddenly becoming animated, with his characteristic humor, he recounted how in 1957 (?) he ended up in a hospital in Moscow with a heart attack. They barely revived him, and then he was treated for a long time. Before his discharge, the attending physician gave a whole lecture on what is permissible and what is contraindicated for a person who has had a heart attack.

“Doctor, what will happen if I don’t follow your prescriptions?” – asked the recovering nearly fifty-year-old professor. “You will die,” the doctor replied. “And if I do?” – the doctor smiled and said: “We will all die someday anyway…” “And I started living as before! Not fearing anything, and I still live,” concluded Boris Mikhailovich with a laugh.

Contrary to the doctors' predictions, he lived, and led a very active creative life for more than 20 more years, loving life even more and, as a necessary part of it – his students…

Then, more than 25 years ago, for some reason, I felt light and simple, and almost joyful after his words. Now, recalling such people as Boris Mikhailovich, I think: “These are the kinds of people who selflessly love Life itself! And this Love for Life is the legacy of our Teacher…”.

Usually, it is not characteristic for a person to pause amidst the daily routine and remember that life, unfortunately, is fleeting, and the legacy left to you by your dear Teacher. And it is in vain…

Notes

1. Bernsham A.N. Archaeological Essay on Northern Kyrgyzstan. – Frunze, 1941. – p. 16.

2. Rerikh Y.N. History of Central Asia. Vol. 1. MCR. – Moscow, 2004. – p. 91.

3. Dyadyuchenko Leonid. On the Path of Time // Literary Kyrgyzstan. – No. 7–9. – 1994. – p. 119.

4. Ibid. – p. 121.

5. Ibid. – p. 123.

Voropaeva V. A.