Weather and its Predictors.

Nomadic life is characterized not only by closeness to nature but also by a significant dependence on it. Therefore, the ability to foresee adverse natural phenomena was an acute practical necessity for people, allowing them to prepare in advance, mitigate the impact, save livestock, and avoid hunger. Not knowing the actual causes of these phenomena, people have long learned to identify events—harbingers that allowed for fairly reliable forecasts by closely observing nature. We previously noted that the most gifted individuals in this regard were called эсепчи (esepchi), жылдыз эсептөөчү (star gazer), аба ырайды билгич (weather forecaster).

However, alongside the genuine connections between phenomena, predictors also attributed imaginary, associative, and not always scientifically consistent relationships.

In weather forecasting, they often relied on the characteristics of the year according to the 12-year animal cycle. For example, it was believed that in the year of the "leopard" and "rabbit," winter would be mild, while in the year of the pig, it would be frosty and cold, etc.

Star gazers, when determining the weather, paid attention to the position of the stars: at what time and in what position relative to each other they were, which provided a more accurate forecast. They could sometimes predict changes in the weather a week or even several months in advance based on the movement and speed of the wind and clouds, as well as conclusions drawn from constant observations of changes in the behavior of migratory birds, domestic and wild animals, spiders, mosquitoes, horseflies, and others. "Kyrgyz people studied the properties and habits of their animals well," noted G. S. Zagryazsky, the head of the Tokmak district, in the late 19th century. "By observing various phenomena in summer, they can determine with sufficient accuracy the duration of winter, hence the time when the rams should be lambing."

Their assumptions, primarily based on empirical observations, constantly generalized and refined from generation to generation, were largely confirmed, which is why the people listened very attentively to the advice of these individuals. For this reason, many accurate and talented forecasters were said: Олуя эмес, бирок олуядан кем эмес — He is not a creator, but not worse than one. They were respected and honored, enjoying great authority.

Kozho Jusup Balasagyn highly valued the work of star gazers. He advised farmers (diykans) and herders (malchylarga) to adhere to their predictions and consult with them in managing their households.

Weather predictors knew on what date and in which month a snowstorm would begin and how many days it would last; when a lot of snow would fall and when it would melt; in which year there would be an early spring, etc. Their predictions were not fabrications; they were based on daily weather observations as well as information inherited from the past and passed down from generation to generation. For example, the esepchi Terekul from Talas predicted changes in the weather based on the strength and direction of the wind. To give an accurate forecast, he conducted the following experiment: on mounds, burial mounds, and elevated places near his yurt, he piled heaps of ash in a conical shape, from the displacement of which he determined where the wind was blowing from and at what time of day and night. He compared this data with previous data that coincided with the day and hour of these measurements, which allowed him to accurately predict the weather for a week ahead and even for a month.

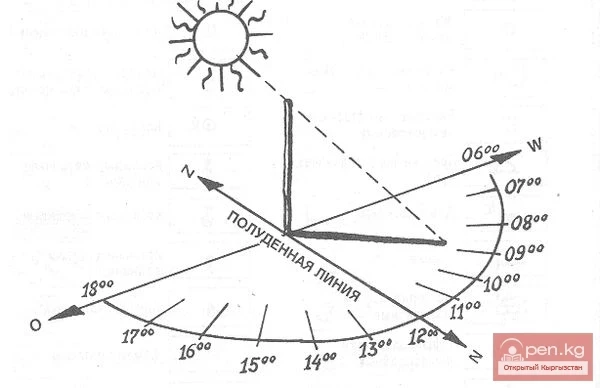

This is how the influence of the wind on weather changes is reflected in folk proverbs: Аба ырайы шамалдан билинет — The weather is known by the wind; Шамал соккон жакта жамгыр жаайт — When the wind blows, it will rain. The esepchi, predicting the weather, based his observations on the following signs: if the wind begins to strengthen and suddenly changes direction, rain will soon come. If the wind becomes stronger and slightly changes direction, it will be cool for a long time. For flat areas, compared to medium and high mountains, observations of changes in wind direction allow for a more accurate weather forecast. For example, if in the Chuy and Talas regions, on rainy days, the wind direction unexpectedly changes from west to east to the opposite—from east to west, the weather will clear up; hence, the Kyrgyz said: Чыгыштан урган шамал эч убакта жамгыр алып келбейт — Wind from the east never brings rain.

A well-known esepchi Kalcha (also from Talas) once, at the end of winter, when the Kyrgyz said: Жаз 'эшиктин алдына келип калды — Spring has come to the doorstep,— observing various changes in the atmosphere (it was cold during the day, but at night it warmed up, even became stuffy) and comparing them with previous data, concluded that bad weather was coming.

Indeed, soon there was heavy snow, followed by a snowstorm. Those who did not heed his prediction suffered great losses due to jute. They did not believe that there could be severe cold, for if the sun shines, it is time for spring to begin: Обу жок оюна келгенди оттой берет да, жаз келип, кун жаркырап тийип турса, каяктан кар жаап, жут болмок эле, взу качан влврун билер бекен? — He babbles whatever comes to his mind. It is warm outside; where will a lot of snow fall, and livestock begin to die? Does he know in advance when he will die?

According to legend, Kalcha died in one of the harsh years, having lost his flock of sheep due to hunger and cold. Hence the saying arose: Эсепчини жут алат — The esepchi will be overtaken by jute.

In sudden changes in weather (the onset of unexpected drought or periods of cold torrential rains turning into heavy snow), esepchi tried to notice what phenomena were occurring in nature, striving to remember them for future weather predictions.

Systematic empirical observations of the weather allow for accurate forecasts even without the use of such commonly used physical instruments today, such as barometers, which measure atmospheric pressure, anemometers, simple weather vanes that determine wind direction and strength, and thermometers, which measure air temperature.

Escepchi noted that clear, dry weather would turn unstable, and even into a storm, if it became colder during the day and warmer at night, stuffy; bad weather would persist for a long time if the day and night were equally warm; similar weather would occur if a sharp warming was felt without strong fluctuations within the next 24 hours.