The sculpture was found during a joint archaeological expedition at the Borombay complex, located near the village of Kyzyl-Oktyabr in the Kemin district. This site, situated in the foothills of the Chui Valley, includes numerous burial mounds and ritual structures spanning different historical eras.

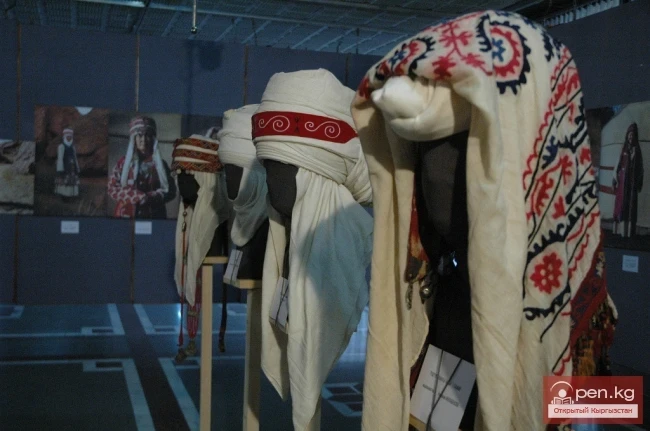

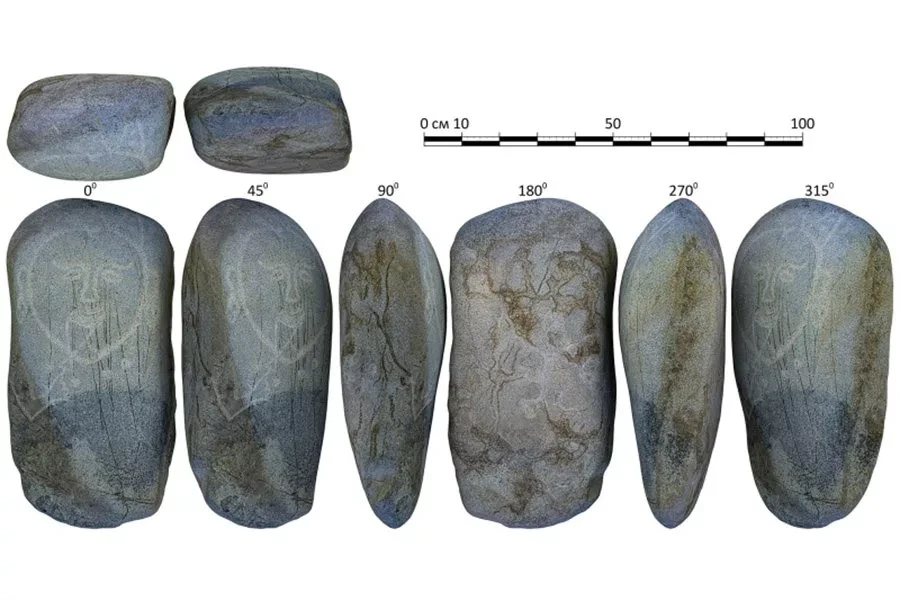

According to Professor Alexey Tishkin, who leads the expedition, the stone image was discovered in close proximity to the Borombay-I burial group. The figure of the woman, carved on a large boulder, features a characteristic three-horned headdress typical of early Turkic iconography. In her right hand, the sculpture holds a bowl — a symbol often associated with ritual offerings and ancestor worship.

“The composition of the boulder differs from local stones, indicating that it was specifically transported to create this image,” Tishkin noted. “This is a rare example of anthropomorphic sculpture from the early Turkic period, depicting a woman rather than a male warrior or ruler.”

The research team conducted detailed photogrammetry of the find and created a 3D model for future publications. The surface of the sculpture shows signs of careful processing, confirming the use of stoneworking technologies in the early Turkic period. This discovery adds to the small but growing corpus of female anthropomorphic sculptures known in Inner Asia and helps to deepen the understanding of the symbolic and social role of women in early Turkic beliefs.

Archaeologists also noted that the three-horned headdress can be interpreted as a symbol of heavenly protection, with analogies in other early Turkic and steppe artistic traditions. Similar motifs can be found in petroglyphs and bronze artifacts from Mongolia and Southern Siberia, indicating shared cultural traditions within the Greater Eurasian Steppe.

In addition to the sculpture, the expedition investigated two major burial sites: the Borombay-I mound No. 39 and the Borombay-II mound No. 8.

Mound No. 39 turned out to be a large catacomb burial consisting of several layers of stones. Although the tomb had been looted in antiquity, researchers found fragments of bones and ceramic vessels that will undergo radiocarbon dating to determine their age.

“This type of catacomb structure has not been observed in the Russian Altai. It likely dates back to the pre-Turkic period and may be associated with the Kengkol culture or earlier traditions,” Tishkin said.

The Borombay-II mound No. 8 was an oval ring of large stones without human remains. Archaeologists interpret it as a cenotaph, a symbolic grave commemorating a person who died far from home. The discovery of a fragment of pottery and a well-crafted stone pestle confirms the ritual nature of this mound.

A total of 41 archaeological sites were registered in the Borombay-I area, including stone enclosures and ritual structures. Unfortunately, many mounds have suffered due to construction work and prolonged agricultural use.

After the excavations were completed, all trenches were filled in and covered with turf to restore the natural landscape. The team emphasized that further research in the Chui Valley will require longer field seasons, additional funding, and active use of digital recording technologies.

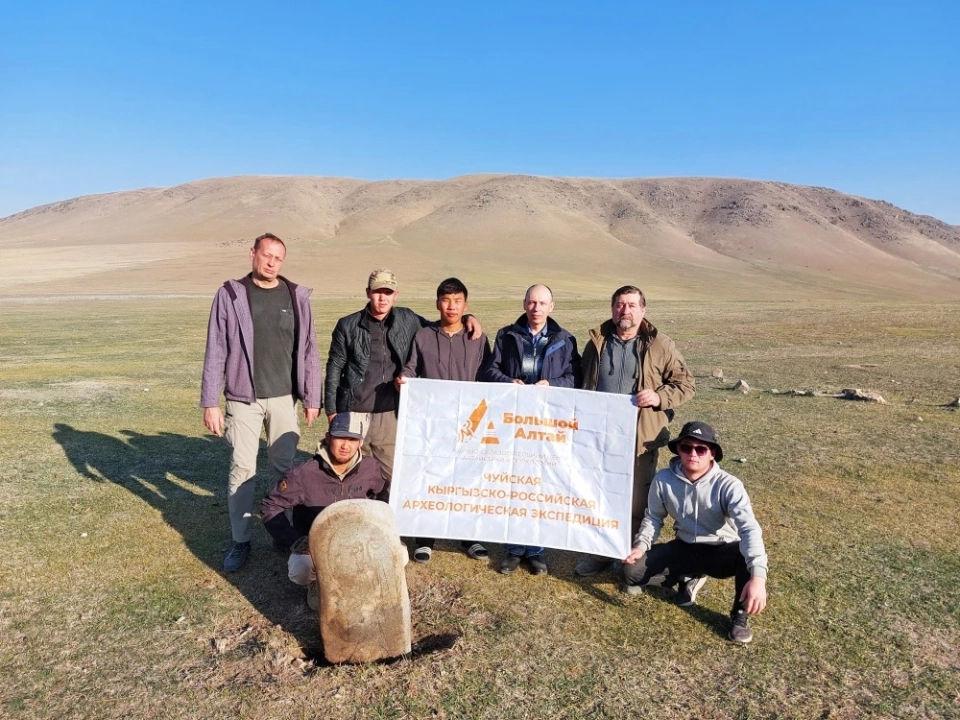

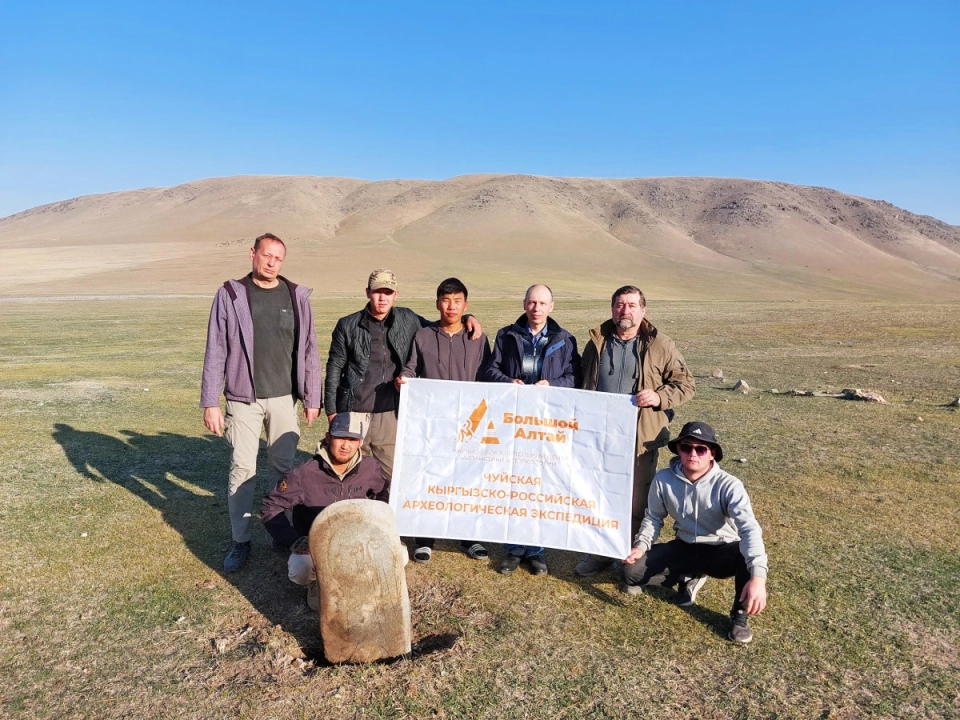

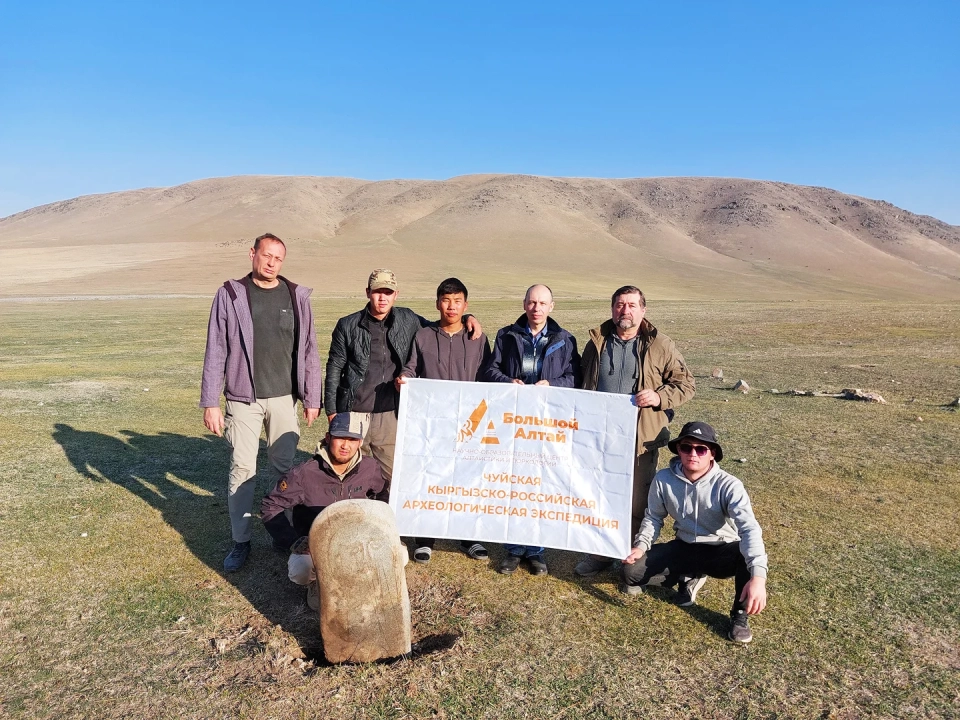

The collaboration between Altai State University and Kyrgyz National University marked the first systematic fieldwork by Altai archaeologists in Kyrgyzstan. Future expeditions will focus on studying the cultural and chronological connections between the ancient cultures of Altai and Central Asia.

“The discovery of the Borombay sculpture represents a new phase in the study of early Turkic monumental art,” Tishkin noted. “It provides direct archaeological evidence of the unity of artistic and ritual perceptions among the nomadic peoples of Greater Altai and the Kyrgyz steppe.”