According to the article by Galiya Ibrahimova, the authorities of Uzbekistan have begun to revert to old methods characteristic of the Karimov era as the initial positive results of reforms started to fade. Instead of further transformations, they preferred to use tried-and-true practices.

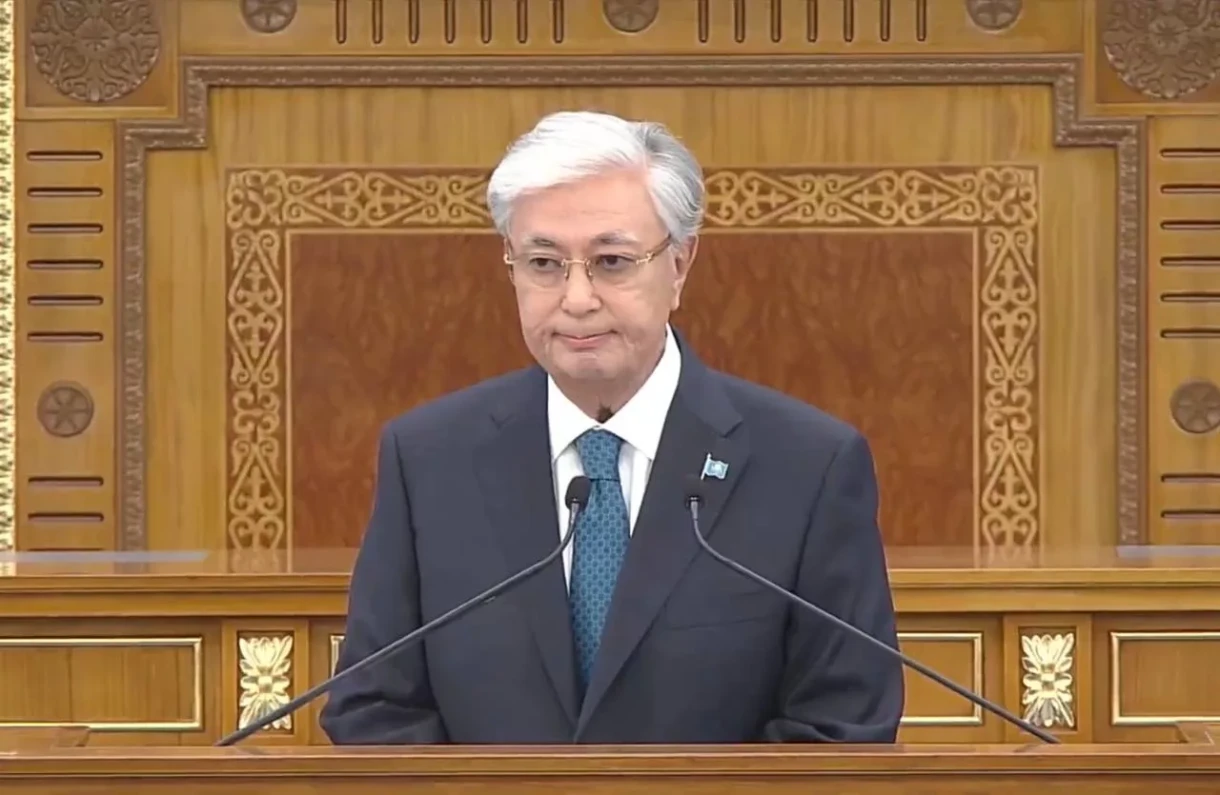

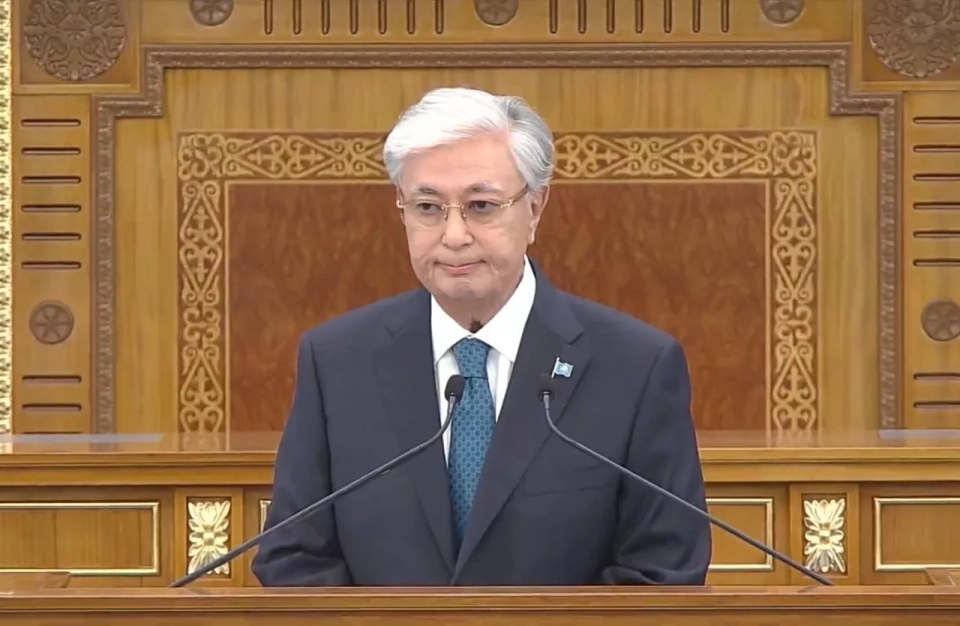

Since coming to power nearly ten years ago, Shavkat Mirziyoyev has portrayed himself as a reformer, contrasting himself with Islam Karimov. However, over time, he has started to return to the methods of his predecessor, including elements of a personality cult.

It is also becoming evident that the president's family is taking an increasingly prominent role in governing the country. Under Karimov, relatives, especially his daughter Gulnara, played a significant role in state affairs, and Mirziyoyev has followed the same path. His eldest daughter, Saida, recently became the head of the presidential administration, effectively making her the second person in the state.

Thus, Mirziyoyev's rule, which was initially perceived as a departure from Karimov's legacy, is becoming increasingly similar to previous practices, albeit with minor elements of modernization.

The fear is gone, but the cult remains

Throughout his rule, Shavkat Mirziyoyev has presented himself as a reformer who is opening Uzbekistan to the world, in contrast to the isolation of the Karimov era. The reform known as "Uzbekistan 2.0" included the liberalization of the economy, the introduction of free currency conversion, reforms in the banking and tax sectors, privatization of the state sector, and the expansion of political rights and freedoms.

The reforms carried out after the closed nature characteristic of the late Karimov period yielded quick results: foreign investments began to flow into the country, large-scale construction projects were launched, business processes were simplified, tourism developed, and unemployment and poverty levels decreased. Uzbekistan is actively establishing international connections and hosting summits, festivals, and sporting events.

One of Mirziyoyev's achievements has been the reduction of the atmosphere of fear that prevailed under Karimov. The authorities significantly reduced the powers of the National Security Service and changed its leadership, appointing Batyr Tursunov, who is the president's brother-in-law, as deputy head. The National Guard, under the control of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, has taken on a key role in the security system.

The president has also gathered a team of young technocrats around him who have begun to implement new practices, including the active use of social media and more open interaction with society. At the same time, regional authorities have been granted more powers in managing local budgets, and businesses have begun to more actively enter international markets.

However, over time, the positive results of the reforms began to wane, and the authorities returned to familiar Karimov practices. For example, the powers of the regions were restricted, as the redistribution of powers led to decisions being made by sometimes incompetent and corrupt regional officials.

Government officials also began to notice that the president's rhetoric increasingly echoed the ideas of his predecessor: Mirziyoyev speaks less about the need to strengthen other branches of power and more about his achievements. As a result, officials quickly realized that the best way to maintain their positions was to demonstrate loyalty and sycophancy towards the head of state. Now public speeches begin with lengthy thanks to the president, and his photographs fill the front pages of newspapers, once again reminding of Karimov's personality cult.

A similar logic has also become evident in the relationship between the state and business. Initially, Mirziyoyev planned to create a layer of modern entrepreneurs whose activity would serve as an additional source of legitimacy for the regime. It was expected that the expansion of market opportunities would lead to political loyalty from the new economic elite.

However, it soon became clear that simply easing state regulation does not guarantee the loyalty of the business community. As a result, important reforms, such as privatization and changes in the agricultural and energy sectors, remained unfinished so that the state could maintain control over business.

The system of distributing benefits was also not reformed: the authorities preferred to continue distributing subsidies based on loyalty rather than the effectiveness of companies. Those who showed excessive independence faced increased tax burdens and frequent inspections.

Overall, the deepening and development of the reforms initiated by Mirziyoyev would imply strengthening the independence of other branches of power and business. However, the regime was not prepared for this. As a result, the logic of power consolidation gradually displaced the initial reformist aspirations.

The family as power

Another characteristic of Mirziyoyev's rule, bringing him closer to the Karimov era, has been the active involvement of his family members in governing the country. His eldest daughter, Saida Mirziyoyeva, soon after her father's rise to power, headed the communications sector in the presidential administration, while her husband, Oybek Tursunov, became the deputy head of this agency.

The younger daughter, Shakhnosa, took the position of first deputy head of the National Agency for Social Protection, while her husband, Otabek Umarov, became the deputy head of the Presidential Security Service. The president's wife, Ziroatkhon Khoshimova, oversaw healthcare and pharmaceuticals and, reportedly, influenced key personnel decisions. Other family members also acquired significant business assets or took important positions in state structures.

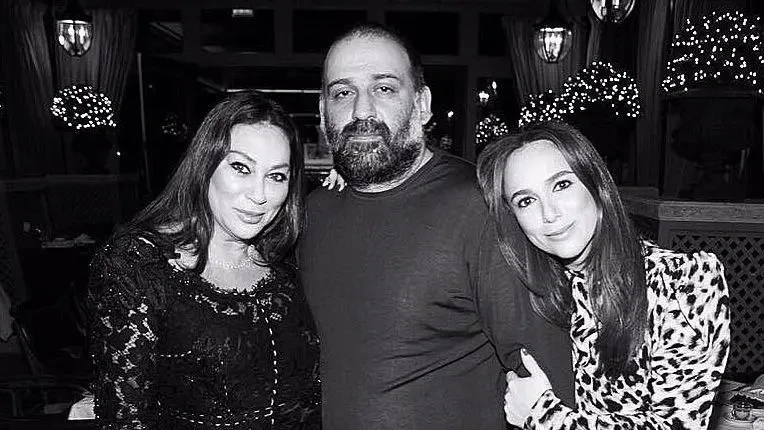

This resembles the times of Karimov when the president's relatives wielded significant influence. For example, Gulnara controlled large business projects with foreign investments, while Timur Tillyaev, the husband of the youngest daughter Lola Karimova, owned the largest market in Tashkent.

At the same time, the political influence of the first president's family was limited: Gulnara's attempt to expand her powers in politics led to a conflict with the security forces, a court case, and house arrest, and later — in 2019 — to her transfer to a general regime colony.

In contrast, the Mirziyoyev family has proven to be more cohesive, and the president likely saw in them a reliable support, especially in the early stages of his rule when he had few trusted individuals, and the loyalty of Karimov's personnel was questionable.

The role of the president's family became particularly noticeable after two crises that occurred during Mirziyoyev's rule. The first occurred in Karakalpakstan in July 2022 when the authorities' attempt to exclude the provision of autonomy for the republic from the Constitution sparked mass protests. To suppress the unrest, as during the events in Andijan in 2005, the authorities used force.

In the winter of 2022–2023, an energy crisis erupted: a shortage of gas left people without heating and light, nearly leading to new protests.

Both crises seriously undermined Mirziyoyev's image as a reformer and liberal while simultaneously increasing his distrust of the bureaucracy. In these conditions, the role of the family circle, primarily Saida Mirziyoyeva, increased. She was entrusted with overseeing the implementation of presidential decisions in Karakalpakstan regarding the modernization of infrastructure and the economic development of the region.

Over time, the powers of the president's daughter expanded, and she began to oversee various socio-economic and infrastructure projects, as well as control the information agenda, including coverage of her father's activities in the media.

Saida became the president's chief confidante, effectively surpassing any minister in her position within the power hierarchy.

However, her rise was not without friction, and rumors of internal conflict arose after the assassination attempt on Komil Allamjonov, the former head of the president's press service and Saida's mentor. Otabek Umarov, the husband of the president's youngest daughter, was named as one of the possible masterminds.

As a result of the conflict, Saida emerged victorious: Umarov was dismissed from the president's security detail, and in the summer of 2025, she headed the presidential administration, solidifying her role in Uzbekistan's political system.

A telling example

Today, Saida Mirziyoyeva's position has strengthened to the point where many consider her a potential successor to the president. There are no formal grounds for a swift change of power: a constitutional reform will reset Mirziyoyev's presidential terms, allowing him to remain in office until 2037. However, discussions about a possible transfer of power along family lines continue.

In practice, she deals with environmental issues in Tashkent and foreign policy: Saida has held meetings with members of the British Parliament, representatives of the EU, WTO leadership, Russian officials, and even with Pope Leo XIV. She also emphasizes that diplomacy is of particular interest to her.

The increasing role of Saida is a natural consequence of the centralization and personalization of power in the hands of the current president. In ten years in office, Shavkat Mirziyoyev has not created a team of trusted individuals from among civil servants nor expanded the powers of other institutions of power. As a result, control over decision-making has remained in the hands of the president and his inner circle. Starting with reforms, Mirziyoyev risks going down in history as yet another autocrat.

It is evident that such reliance on family is an attempt to ensure security for himself and his loved ones in case of leaving power. However, this strategy has repeatedly proven ineffective. In the long term, a governance system lacking strong institutions and developed legal mechanisms cannot guarantee stability and security for Shavkat Mirziyoyev and his family. The transfer of power by inheritance is a complex task even in Central Asia, and with the arrival of a new leader, any informal rules and promises lose their force. The fate of Gulnara Karimova, who is still in prison, and other members of the first president's family in Uzbekistan is a vivid testament to this.