He, a representative of the old aristocracy who became a people's commissar, demonstrated that true nobility is measured not by lineage but by what benefits the people.

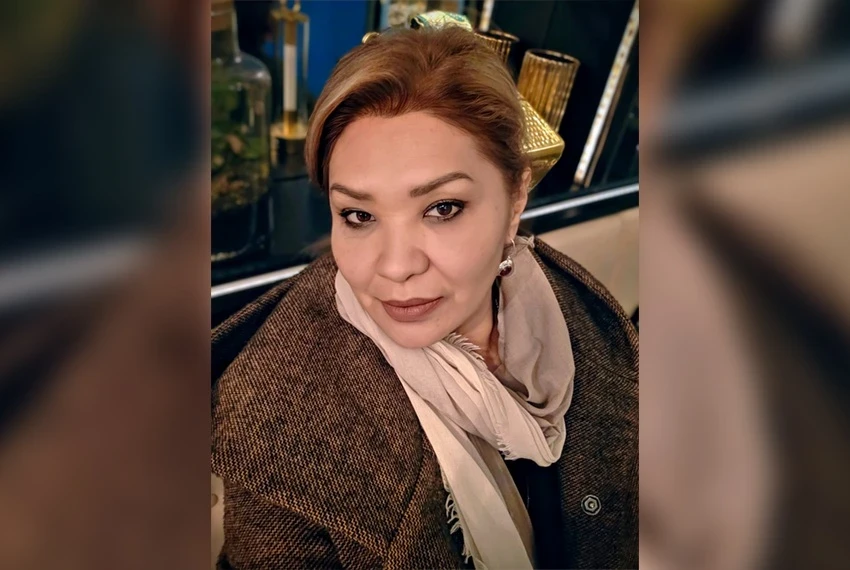

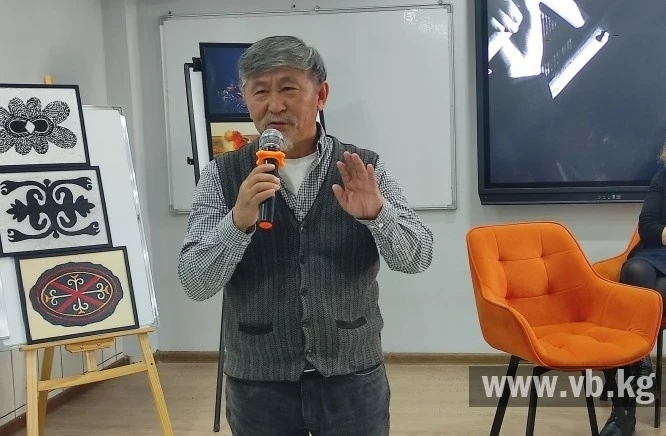

Dali Myrza's grandson, Oleg Zulfi Baev, shared memories of his grandfather with 24.kg, and the material is supplemented with opinions from relatives and close ones.

Roots and Honor: Descendant of Kurmanjan Datka

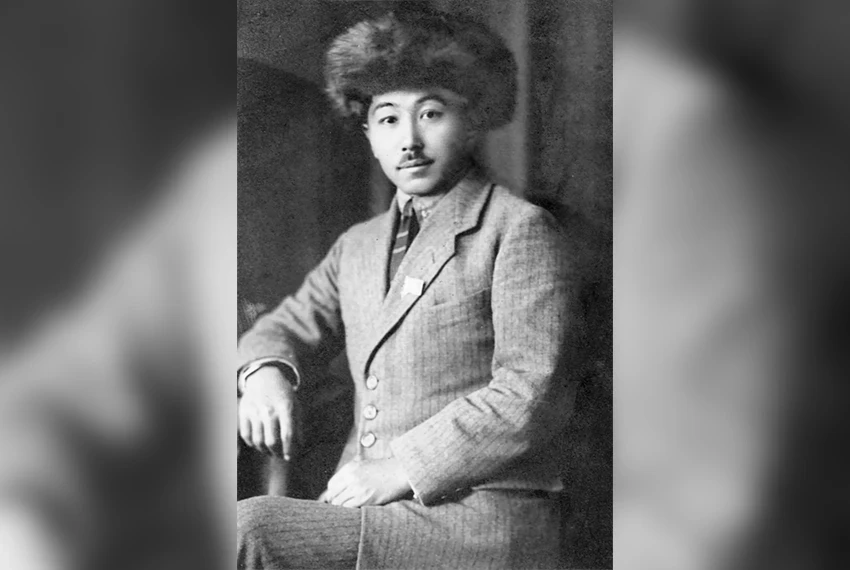

Dali Myrza Zulfi Baev was born on June 1, 1896, in the village of Tyuleyken in the Osh district, in the family of a respected village elder, Zulpubay-Sarkara, the nephew of Kurmanjan Datka.His mother, Nurbiybu, was the daughter of the akim of the Osh vilayet, Jarkynbay Datka, who, in turn, was the son of the ruler of the Alai Kyrgyz, Alymbek Datka, from his first wife.

According to his grandson, Dali himself added the title "myrza" to his name.

“Dali Myrza was a grandnephew of Kurmanjan Datka; both came from the "mongush" clan. Dali's father, Zulpuqar, was the son of Karybek, a favorite of Kurmanjan Datka. Karybek, in turn, was the son of the sister of the ruler of Alai, Alymbek Datka, and was known as a literate person.

Despite his noble lineage, Dali Myrza chose the path of enlightenment and state reforms, not content with a quiet life.

“High lineage is not a privilege but a duty. The true obligation of everyone is to serve the people,” — these words became the foundation of his activities. He became a bridge between the nomadic aristocracy and the new intelligentsia,” — noted Oleg Zulfi Baev.

Like many Kyrgyz intellectuals, Dali began his education at the Alymbek Datka madrasah, where his uncle, Jamshitbek Karybekov, a well-known figure in the south of the country, taught.

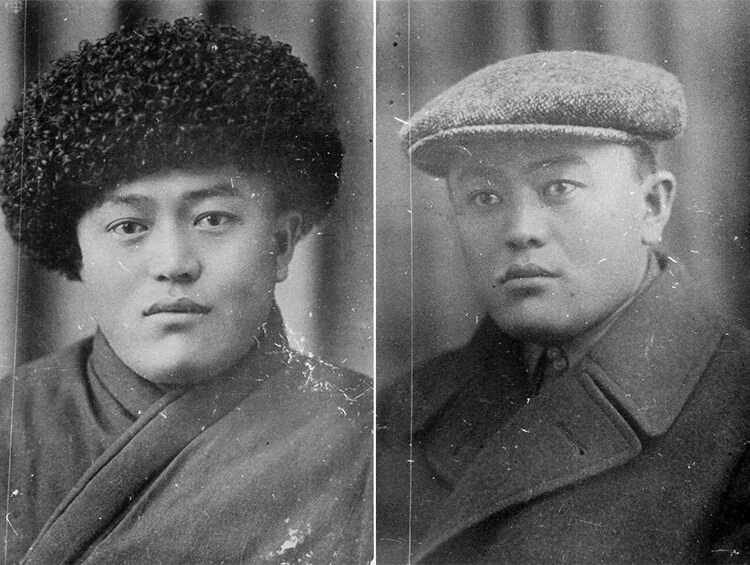

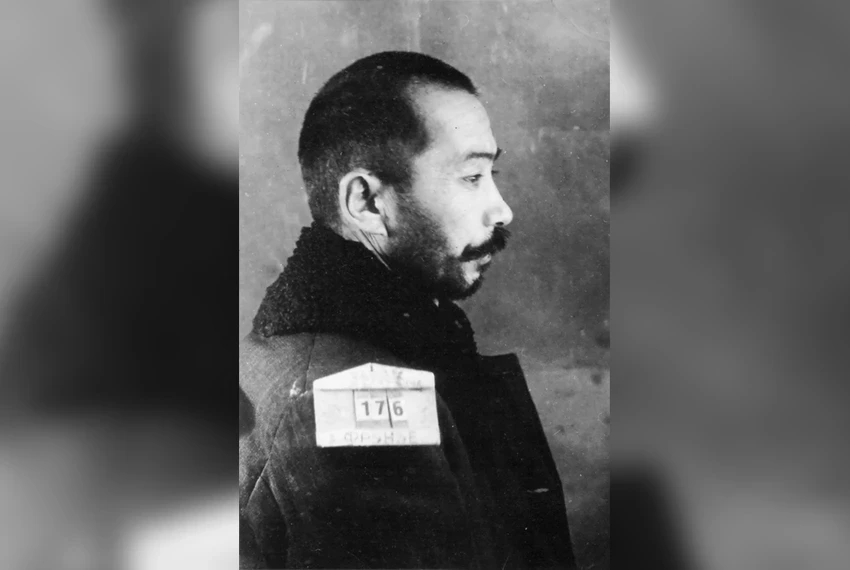

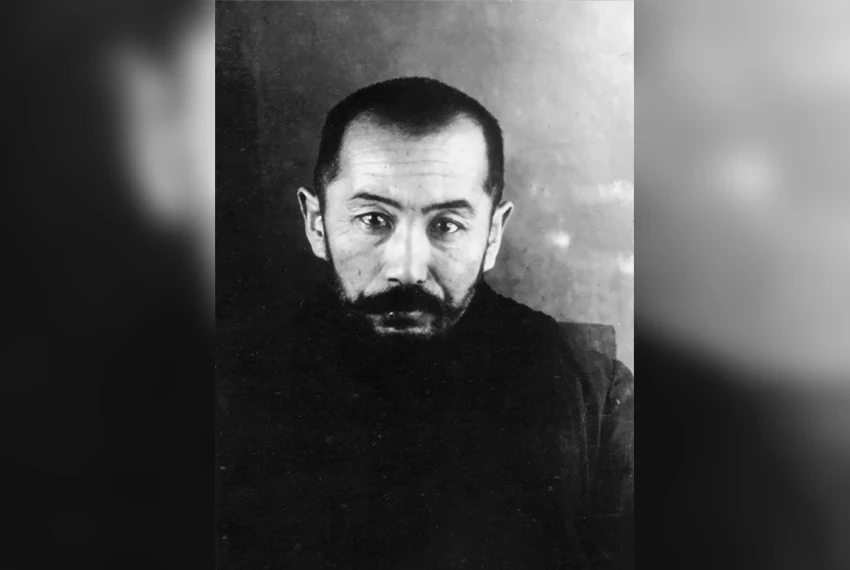

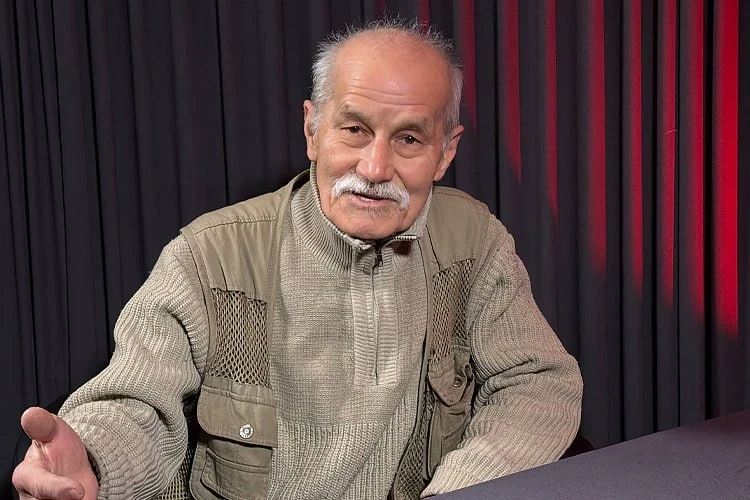

Photo from the family archive. Dali Myrza Zulfi Baev

In 1915, he graduated with honors from the Osh Russian-Tuzem school, being fluent in Kyrgyz, Russian, and Uzbek, as well as Arabic literacy. After his studies, he began working in the colonial administration, which was common for the first Kyrgyz public figures. From 1915 to April 1917, he served as a translator-clerk in the Osh district administration, where he gained his first management skills.

Transition to Revolutionary Changes

From the very beginning of the October Revolution, Dali became a supporter of the new government. From 1917 to 1920, he served as secretary of the Kashgar-Kishlak and then Osh volost revolutionary committee. He studied in Tashkent at teacher training courses and taught Uzbek language at the first Soviet school in Osh.In April 1920, he joined the Bolshevik party and was assigned to administrative work. From 1920 to 1924, he worked as a controller of the Osh RKI, chairman of the Kashgar-Kishlak district executive committee, responsible secretary of the Osh city party committee, and prosecutor of the Osh district. In 1922, he was elected a member of the TurkCIC of the Turkestan republic.

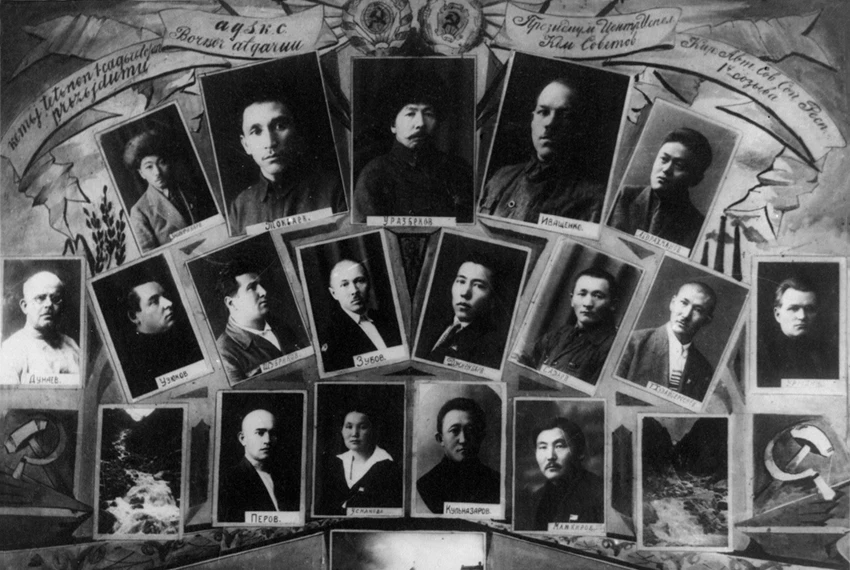

National-State Construction

According to his grandson, in his native Osh, the elders always took pride in Dali's high level of education and his devotion to his country.“People turned to him for advice and help on any issues. His contribution to the development of Kyrgyz statehood during those difficult times was confirmed by the appointments and high positions he held,” — he added.

The success of Dali Myrza began with the formation of the Kara-Kyrgyz Autonomous Region, when Kyrgyz people found it difficult to compete with Uzbek cadres in the Fergana region, where they were a minority.

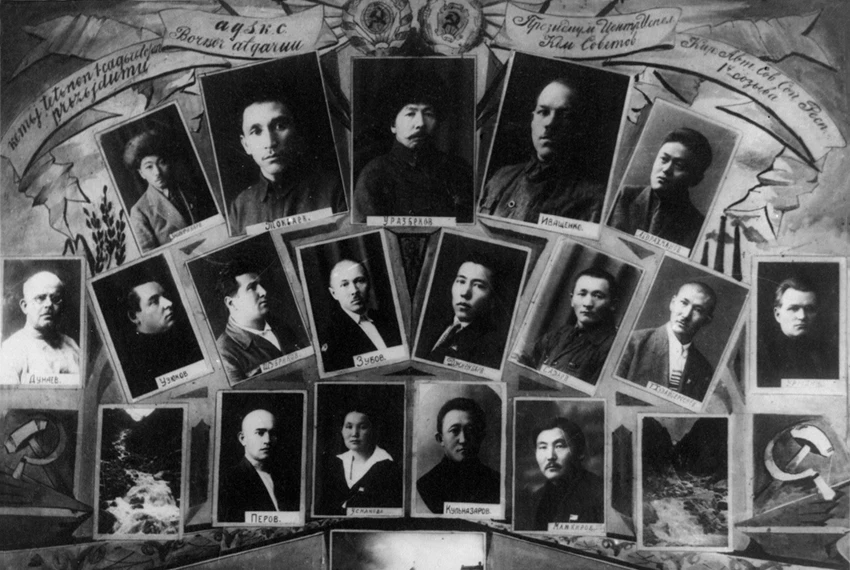

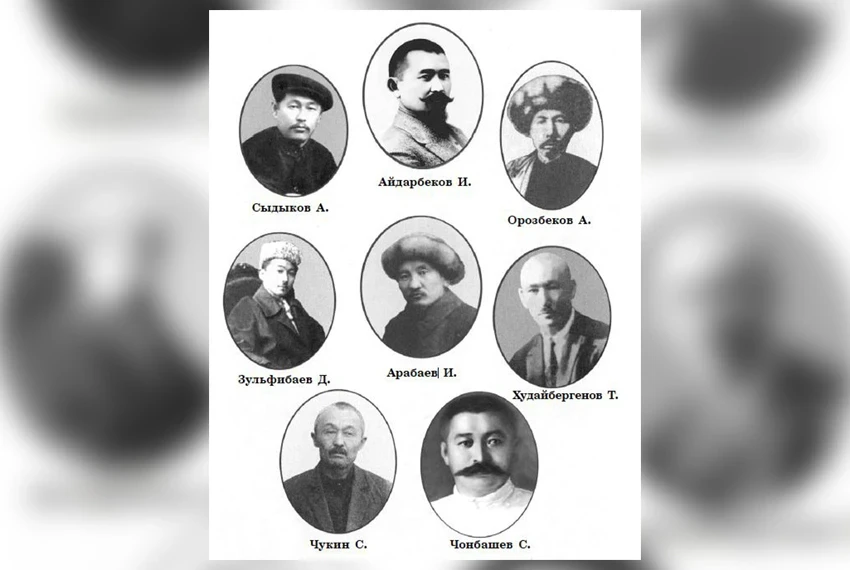

In the autumn of 1924, during the creation of temporary governing bodies of Kara-Kyrgyzstan — the Orgpartburo and the Oblrevkom, Zulfi Baev was appointed deputy chairman of the Oblrevkom and then headed the Osh district revkom and district executive committee. Moving to Pishpek, he became close to leading political figures of Kyrgyzstan, such as Abdykerim Sydykov, Jusup Abdrakhmanov, Imanaly Aydarbekov, Ishenaly Arabaev, and Abdykadir Orozbekov,” — noted Oleg Zulfi Baev.

Opposition and the "Thirty's Case"

In June 1925, Dali became one of 30 members of the opposition who opposed the personnel policy of the Kirov regional committee, demanding:* selection of personnel based on business qualities rather than group affiliation;

* translation of documentation into the Kyrgyz language;

* fair resolution of land issues for Kyrgyz and Europeans;

* cessation of petty supervision by the Soviets over party bodies.

As a result, he received a severe reprimand and was removed from the position of chairman of the Osh council, after which he headed the agriculture department of the Kirov regional executive committee.

Despite the pressure, the leadership of Central Asia recognized Zulfi Baev as one of the most educated and authoritative workers of the republic, and he was not expelled from the party, as happened with Abdykerim Sydykov and Ishenaly Arabaev.

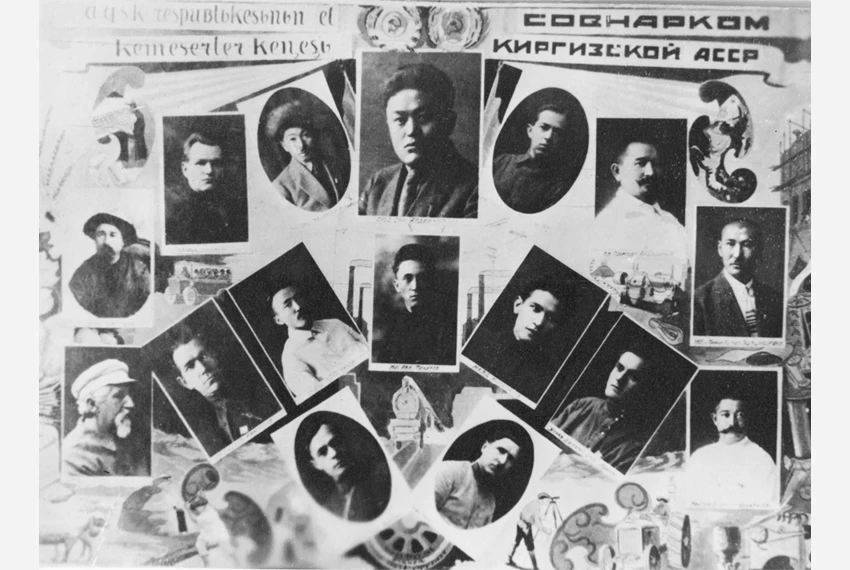

Service in the Government and Narcomzem

In 1927, Dali became a member of the KirCIC and joined the government of Jusup Abdrakhmanov, taking the position of deputy chairman of the Council of People's Commissars and Narcom of agriculture. He also served on the Executive Bureau of the Kirov regional committee of the party.As Narcom of agriculture, he managed to restore pre-war levels of agricultural production by 1928.

He dealt with border conflicts with Uzbekistan, led infrastructure projects, including the construction of the Tokmak railway, and studied in Tashkent at the Central Asian Bureau courses.

Struggle Against Basmachism and Slander

In 1929, he was often sent as a commissioner to fight against the "basmachi," who were actually peasants resisting brutal collectivization. However, official propaganda labeled them as "bandits."Negative characteristics were compiled against Dali Myrza. The first secretary M. Kamensky wrote: “Dali Zulfi Baev — a party member, a large bai, maintains contact with some basmachi, a great chauvinist.” These accusations were unfounded and were an attempt to discredit him before the leadership, notes Oleg Zulfi Baev.

Years of Pressure and Repression

From the late 1920s, Dali attracted increased attention from the NKVD. His involvement in the opposition and "social origin" became the main topics of discussion.In 1930, he headed the Ton district executive committee, then worked as deputy chairman of the Uzgen district executive committee. In 1932, he received a severe reprimand "for disrupting grain procurement," similar to that given to Jusup Abdrakhmanov, who effectively saved people from starvation by ordering the distribution of bread to the population.

From 1932 to 1933, Dali Zulfi Baev served as deputy Narcom of education. In 1934–1936, he headed the Kirvodkhoz and participated in the development of Kyrgyz scientific terminology.

Later, he became the director of the MTS in the Naryn district. In May 1936, he was expelled from the party and moved to Osh, where he worked as an instructor in the inter-district office of "Glavmyaso."

Family Life

Dali Myrza Zulfi Baev had five children, but only three survived: daughter Kamilya and sons Engel and Erkin.

The Zulfi Baev family lived in a large house near the Osh National Drama Theater, not far from the local prison. This place is associated with heavy memories for Dali Myrza's children.

The family was close-knit and numerous. Dali Myrza was often absent for long hours, so the primary upbringing of the children was taken on by his wife Khayriniso, who was 11 years younger than her husband. Despite his great affection for his sons Erkin and Engel, he tried not to spoil them. A joyful moment for him was the birth of his youngest daughter Kamilya.

He chose names for his children with deep meaning, and his decisions in the family were not disputed, as everyone knew of his strict, sometimes hot-tempered nature.

In his free time, Dali loved to play the dutar and chess.

Later, his wife often recalled the last years of her husband's life, sharing bitter memories with the children. They became her only joy in difficult times.

The children remember well how their mother spoke of the fears associated with the possible arrest of their father and his friends. Friends often warned Dali Myrza and suggested he leave the country, but he always replied: “I have a clear conscience, and I have nothing to fear...”.

Arrest and Death

However, that terrible moment eventually came. On one of the hot summer days, when nothing foreshadowed trouble, Dali Myrza Zulfi Baev became a victim of the inhumane Stalinist system. On August 5, 1937, he was arrested.“My brother Erkin and I were playing outside,” recalls middle son Engel. “A car arrived, and my father was not even given the chance to change clothes. He was taken out in his home clothes and taken away, but that was not the last day I saw my father.”

Every day, eight-year-old Engel ran to the Osh prison, peering through the windows, hoping to see his father.

Dali was sometimes brought out to a room with windows facing the yard. On one of those days, Engel saw his father's silhouette in the window.

“I was very happy, my heart raced,” recalls Engel years later. “My father looked at me and smiled, but then his gaze became sad. He gestured that he wanted to smoke.” At home, no one believed that he was asking for cigarettes, as Dali Myrza never smoked, but the request was fulfilled nonetheless.

After a while, while playing outside, the children saw their father being taken out into the street. They called for their mother and grandmother, hoping he would be released. Later, their mother tearfully recalled the last meeting with her husband.

“That day he was calm and confident. He did not show weakness or fear for a moment. His last words: don’t be afraid, everything will be fine. My friends will not leave you.” Dali was not released; he was taken away in a car.

Waiting and Suffering

Friends did not come to help, and acquaintances and relatives turned away. For those around, the Zulfi Baev family became "the family of an enemy of the people." These times were especially hard. The young woman had to cope with difficulties: their house was confiscated, and she had three small children. Zulfi Baev's wife got a job at a silk farm to feed the children, and even irregular work with bonuses did not always help make ends meet.

The children took care of each other. The little daughter often asked, “If dad comes back, how will I recognize him? I have to open the door for him.” In her childlike soul lived the hope that her father would return, and this hope did not leave the other family members.

“Mom often took warm clothes for dad to the prison,” — relatives recall. “But they wouldn’t accept them, and she would return home with a large bundle in her hands.”

The family did not know that on November 5, 1938, the Military Collegium sentenced Dali to execution on charges of participating in the "insurgent nationalist organization — the Social-Turan Party." He was shot in the courtyard of the prison in Frunze along with Jusup Abdrakhmanov, Torokul Aitmatov, and others.

Legacy and Memory

According to his grandson, after the arrest of Dali Zulfi Baev, his grandmother's brother took the family to his home in Tyuleyken.“For many years, the family lived with the hope that Dali was alive, as they were never informed of the verdict. The stigma of "children of an enemy of the people" haunted the sons and daughter throughout their lives. In school and even in adulthood, the Zulfi Baevs faced difficulties and humiliations.

For example, the eldest son Erkin, who graduated from a Russian military school and distinguished himself in service, did not receive high ranks for a long time simply because his father was considered "an enemy of the people." He was not allowed to join the party. Only after the rehabilitation of his father's name was the family's stigma of shame lifted. Erkin became a colonel, served as deputy chairman of the Veterans Council, and joined the Communist Party.

Later, the family returned to the southern capital and lived in a large house, where one half belonged to the brother of Zulfi Baev's wife, who worked in the KGB,” — added Oleg Zulfi Baev.

He recalled that in the early 1990s, when he and his brother visited the KGB in search of archival documents about their grandfather, they were shown his personal file.

“I started reading it, and there were drops of blood on it. Apparently, they were beaten to extract confessions,” — he added.

Creative Path

Oleg Zulfi Baev did not want to follow in his father's footsteps and become a military man. He was named Oleg after his father's comrade Vasily.

“I have always loved to sing. While studying in school, I participated in various competitions. Then I moved to Bishkek and graduated from the Kyrgyz State Institute of Arts. I dedicated most of my life to working as a soloist in the opera and ballet theater, the Philharmonic, and other cultural institutions, performing many roles from famous operas. Now I am retired, but I still give private lessons,” — he added.

Oleg also noted that he has spent his whole life searching for information about his ancestors, studying genealogy, and recalls Pushkin's words: “It is not only possible but necessary to be proud of the glory of one's ancestors.”

Memory of Dali Myrza

In 1991, the remains of Dali Myrza Zulfi Baev and other repressed individuals were reburied in the memorial complex "Ata-Beyit" in Chon-Tash. On June 27, 1957, he was posthumously rehabilitated.Descendants of Dali Myrza strive to immortalize his name by proposing to name streets in Osh, rename the Osh Pedagogical Institute in his honor, and erect a monument, hoping for the swift realization of these plans.

The name of this reformer was long forgotten, and only after decades was historical justice restored.

“A worthy and noble person does not think of himself; he thinks of the benefit of the people,” — the words of Dali Myrza remain a moral code for all who take responsibility for their country.