Hero of the Soviet Union Akucionok Petr Antonovich

Petr Antonovich Akucionok was born on March 25, 1922, in the village of Shumilino, Sirotinsky district, Vitebsk region. Belarusian. Komsomol member. After finishing eight grades of school, he worked as a cultural worker.

With the arrival of the German-Fascist invaders on Belarusian soil, he actively participated in a group of Komsomol members from Shumilino in the elimination of enemy spies, saboteurs, and scouts. He was then evacuated and ended up in Kyrgyzstan, in the city of Tash-Kumyr, where he worked at the "Kapitalnaya" mine. In January 1942, he was drafted into the Soviet Army. In 1943, he graduated from a military school with the rank of junior lieutenant. He was a commander of a rifle squad.

He participated in the battles of the Great Patriotic War starting in February 1943 as part of the Central Front. On October 30, 1943, for his courage and bravery, he was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. He was buried in a mass grave in the city of Loyev, Gomel region. A memorial plaque with the names of four Heroes of the Soviet Union was installed at the mass grave.

HE FULFILLED THE ORDER

The city settlement of Shumilino, drowning in greenery, resembled a disturbed anthill. From the first days of the war, finding itself at the crossroads of front roads, it lived with the tense, pulsating rhythm of worries and concerns.

Day and night, marching companies hurried along its narrow streets, and endless streams of exhausted, destitute, and homeless people flowed through.

Day and night, trains passed through the settlement. They took Red Army soldiers, military equipment, and shells to the west, and evacuated factories, plants, the wounded, children, and women to the east.

Soon, the first enemy paratroopers appeared in the surrounding forests, and a voluntary enlistment for the people's extermination battalion opened at the district party committee.

At that time, Shumilino Komsomol member Petr Akucionok was nineteen. Becoming one of the youngest militia members, he spent days and nights on the most important strategic roads of the district, kept round-the-clock watch in the surrounding forests and at production facilities, and patrolled the approaches to the railway station.

Preparing, like the entire extermination battalion, to be called into active army service or to go into the partisans, he was even taken aback when he received the order to accompany one of the last trains with factory equipment and machines deep into the country. The train was leaving immediately, and there was no time to appeal the unjust order, in his opinion, or to run home, so Petr jumped onto the step of the car.

It was a heavy hour of parting with the dear places that passed by, with his native Belarus.

After two pedali, the annoying and rumbling sound of wheels on the rails finally ceased, and Petr looked with surprise at the unfamiliar mining settlement of Tash-Kumyr in southern Kyrgyzstan.

It was like a miracle: the majestic snow-white peaks on the melting horizon from the heat, the blue sky without a single cloud, the bottomless blue sky, the noisy chatter of mountain rivers, the riot of fruitful gardens, so unlike their own gardens, and the scorching sun. Everything around was quiet, peaceful, and he did not want to think about the fact that in Belarus it was now hot from the burning torches of wooden huts, that bombs and shells were exploding everywhere.

Living with thoughts of the front, Petr did not intend to linger in the rear, but it turned out differently. The mining settlement, which had already sent its main workforce to the front, now needed help, and the military enlistment office temporarily suspended the recruitment of volunteers.

As veteran of the "Kapitalnaya" mine Mikhail Nikolayevich Akimov recalls, this tall blond boy worked as a blacksmith's assistant, then as a blacksmith, and worked diligently. He repaired carts for hauling rock, shaped picks on the anvil, prepared saw blades for shifts, and restored other mining equipment. He quickly got involved in the work, although it was unfamiliar to him before. The mine was mainly worked by women, the elderly, and teenagers. A pair of strong hands was valued like gold at that time. But, of course, he lived with hopes for change.

The long-awaited draft notice from the military enlistment office came only at the beginning of 1942. Having grown up in Belarus and having received real working experience at the Tash-Kumyr mine, he left with the blessing of the Kyrgyz people to fight the hated enemy and swore at a rally to be worthy of this great trust.

His natural courage, organizational skills, and the resilience gained at the mine were soon noticed by the command, and the young man was sent to short-term courses for command staff. After completing them, with the rank of junior lieutenant, Petr Akucionok became the commander of a platoon in the 52nd separate motorized rifle battalion of the 193rd rifle division and received his combat baptism on the Volga.

In early October 1943, he was destined to find himself in the area of the city of Loyev, by the gray Dnieper, on the right bank of which his native Belarus began.

Petr gazed at the opposite steep bank, shrouded in mist, until his eyes hurt, and with a pounding heart thought about when he would rush up its rugged cliffs, pouring lead on the fascists from his machine gun, burst into enemy trenches, and the enemy would not withstand his fury, his devastating fire, and would flee, cleansing the sacred land of his ancestors.

For the upcoming operation of the first breakthrough, the division commander Colonel Frolenko ordered the allocation of a battalion from the 685th and 883rd rifle regiments. The commander of the 685th regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Nikonov, named their battalion, the battalion of Major Vladimir Fyodorovich Nesterov, which had distinguished itself earlier in battles on the Volga and the Kursk Bulge, confidently acting under the difficult conditions of crossing several water obstacles.

The initial thrust across the Dnieper was planned near the village of Kamyanka, to the left of the sandy island of Khovrenkov, and four days were allocated for its preparation. However, having studied the situation and the enemy's fire system in detail, calculating the "dead zones"—unshootable areas formed by steep banks—the commander Nesterov changed this plan.

The crossing was moved north of the well-fortified island across a shaky peat meadow overgrown with low bushes and a sandy spit.

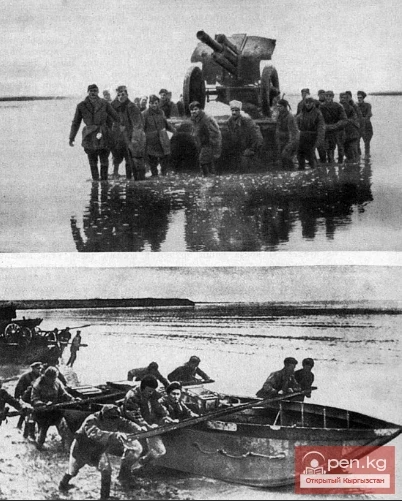

In advance, 70 rafts were prepared for the paratroopers, who were intensively training on lakes and ponds a few kilometers from Kamyanka. Local fishermen pulled out boats hidden from the fascists from the reeds.

The attack was scheduled for the morning of October 14, and in the evening, as per tradition, a party-Komsomol meeting was held.

Opening it, the party organizer of the battalion, junior lieutenant Ivan Tsymbal, briefly said:

— You are called upon by the destitute, but undefeated old men and children of war-scorched Belarus. The fascists consider their positions here impregnable; they have called them the "Military Rampart," so let us show them what our liberator warrior is like. To win, we must fight tomorrow not for life, but for death. And we will win, I am sure!

Their party organizer was young and passionate. A month earlier, the divisional newspaper "Into Battle" wrote about him: "After a fierce battle, two enemy tanks remained on the battlefield. Party organizer Tsymbal stealthily approached one of them and, having confirmed that it could fire, turned the gun around. This was a stunningly unexpected fire from their own tank for the Nazis..."

Then the battalion's komsorg, junior lieutenant Mordasov, asked for the floor. Calling to mark the 25th anniversary of the VLKSM with a successful crossing of the river, he assured that the Komsomol members of the battalion would be at the forefront of the landing.

Petr Akucionok also stood up.

— This flag with the inscription "For our Soviet Motherland,"— declared the junior lieutenant,— I ask to entrust to me.

I swear to hoist it tomorrow morning at the highest point of the Belarusian bank. His request was granted.

At dawn, a fiery whirlwind rose over the impregnable right bank. The sappers Nesterovich, Slastin, and Ilyichev took their positions. Their task was to prepare the floating means for launching into the water and to build temporary piers. The celebrated "Katyushas" took their starting positions. The red-starred attack aircraft flew over the ancient river, which was submerged in pre-dawn sleep, at low altitude.

A signal rocket soared. Major Nesterov was the first to step into the boat standing next to Akucionok's raft.

— Death to the fascist occupiers! — shouted the junior lieutenant and unfurled the entrusted banner in the wind.

According to calculations, it would take about thirty minutes to reach the opposite bank.

The water boiled from the explosions. Boats and rafts were shattered by direct hits. From one of them, a 45-millimeter gun was sliding into the water, tipping over.

— Gun! Gun! Spitsin! — the young commander could only shout in that hell.

But Sergeant Spitsin understood him and was already in the water. Diving once, then again, he managed to tie a rope and swam it to the shore.

About fifteen meters away, the fighters of the machine gun squad of Sherstobitov were also diving into the cold leaden water, trying to find the "Maxim" that had sunk.

— Hooray! — shouted the platoon commander, straining his voice with all the power that overwhelmed him, and, waving the banner, jumped onto the shore.

— Hooray! — echoed over the water along the Dnieper.

The raft was mutilated, barely keeping afloat by a miracle. The others that reached the shore looked no better.

To the left, the platoon of junior lieutenant Besscenny was landing. Clear commands were heard from the commander who had "baptized" himself twice along with Akucionok as he stepped off the raft.

— Forward, guys! To the height! — came the encouraging command of Major Nesterov.

Just a few minutes earlier, thrown from the boat, he was floundering in the river, and now he was darting along the shore as if nothing had happened.

The attack developed rapidly. Artillerymen and mortarmen shifted their fire to suppress the enemy's defenses. The battalion was breaking through to the island.

The fighters were climbing the twenty-meter banks as if they were storming an unprecedentedly high wall. Grenades were used, and soon it came to hand-to-hand combat. The platoon of Akucionok accounted for about 20 fascists killed, four of whom were personally killed by the commander.

The enemy came to his senses. He had many more forces than the attackers.

The political officer of the battalion, Ivan Mordasov, fell, struck by a bullet. Clutching his wound, the party organizer Ivan Tsymbal was giving his clear commands. The attack was faltering.

When it finally dawned, a report came that the other battalions and units had failed to break through.

Strong covering fire from the island either destroyed them or forced them to turn back.

Something incredible had to be done, on the edge of desperate risk. But what? In the sector of the previously planned crossing, the sappers were laying a smoke screen; apparently, a new support landing was being prepared there. The fire of artillery and mortars was shifted to the heavily fortified islands.

— That's it, we are exhausted, — said machine gunner Sherstobitov, falling to the ground next to the platoon commander. — We will have to dig in, comrade junior lieutenant.

But this could not be allowed; it was absolutely necessary to keep the attacking momentum alive. By any effort, at any cost, because they would still be less than what would be needed tomorrow when the enemy regrouped.

— For our Motherland! For Soviet Belarus! — the junior lieutenant stood tall, waving the banner. — Forward!

Rushing ahead, shielding the banner bearer, Sergeant Tashmamat Dzhumabajev burst into the enemy trenches.

Soaked in blood, heavily wounded, the senior medical service sergeant, communist Anna Chichirina, dragged an injured fighter up the slope...

The battle lasted a long time. There were still daring attacks and desperate counterattacks, but the battalion had already firmly established itself on the dominating heights, over which the red banner was triumphantly waving, and, receiving the long-awaited reinforcements at night, in the morning struck the enemy with renewed strength.

And they drove him back, expanding the bridgehead. But Petr Akucionok was no longer in the advancing line; he heroically fell.

On the night of October 16-17, all units of the division crossed the Dnieper. The bridgehead expanded five kilometers deep.

The troops of the 27th corps of the 65th army, including Nesterov's men, as the battalion of Major Nesterov was now called everywhere, confidently developed their success.

Fifty warriors of the division were awarded the highest honor for this breakthrough—the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Moreover, 22 of them were from the same battalion, from Major Nesterov's battalion. Among them were already familiar to us Sergeant Dzhumabajev and Junior Lieutenant Akucionok, Private Samusev and Lieutenant Besscenny, Commander Nesterov, and others.

This was an extremely rare example of such mass self-sacrifice and heroism, even for our Armed Forces, comparable, perhaps, to the unparalleled feat of the 28 Panfilov heroes near Moscow.

Candidate of Military Sciences, Colonel I. Degtyarev wrote in an article "The Division Fights for the Dnieper," published in one of the issues of the "Military Historical Journal" in 1967, that "the significance of the success of the division, which received the name 'Dnieper' after this operation, lies not only in the fact that it broke through the deeply echeloned defense of the enemy but, most importantly, managed to seize a favorable position with very limited forces under unfavorable conditions, thereby ensuring the entry of the second echelon of the corps into battle."

The sister of the Hero, Antonina Antonovna, recalls:

— Petya was born on March 25, 1922. He joined the pioneers in school, then the Komsomol. After seven grades, he went to work, was a good public figure, played in the brass band of the House of Culture, participated in amateur performances. He was fond of sports, and was one of the first boys in Shumilino to meet the standards of the Voroshilov shooter. Independent beyond his years and always composed, he was very responsive to people and caring. It is bitter to realize that he is no longer with us, that his life was cut off so irrevocably early, but all of us who knew and remember Petya are proud of him. And we would like others to be proud of him too. Not only on his native Belarusian land, which he liberated and where he fell, but also in distant mountainous Kyrgyzstan, from where he went to fight.

What can be said? The warrior who fulfilled his given order will never be forgotten by Soviet Kyrgyzstan and its youth. There is no doubt about that.

A. SOROKIN