Report of the Chief of the Pishpek District to the Semirechye Regional Administration on the Place and Role of Shabdan Jantayev among the Kara-Kirgiz. Part - 1

Part - 1

City of Pishpek March 18, 1896

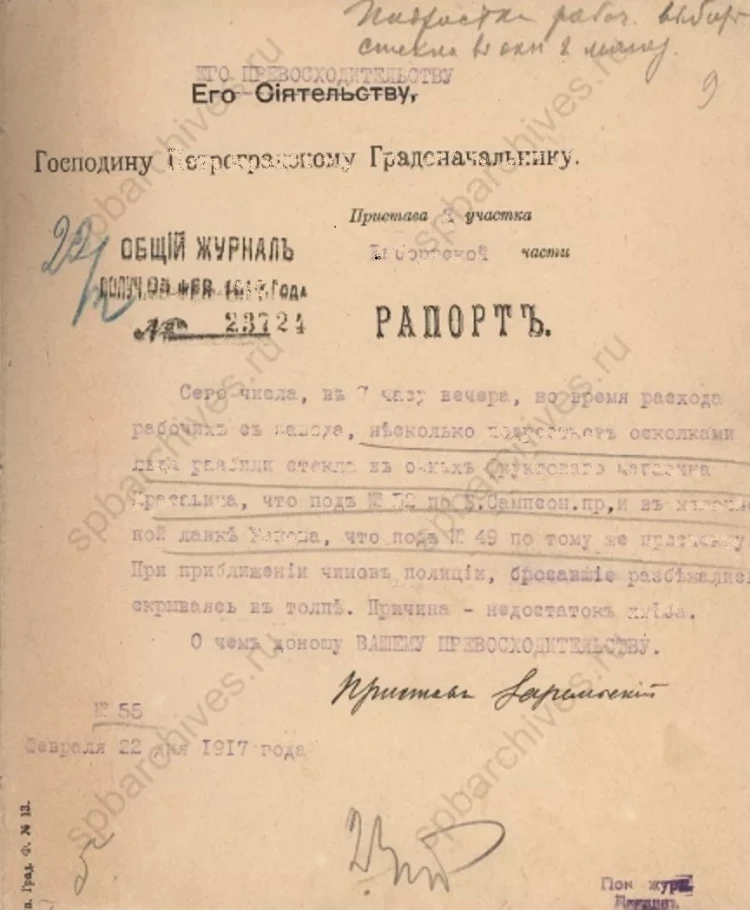

In response to the letters from the commander of the troops of the Transcaspian region No. 809 and the commander of the Transcaspian Cossack cavalry brigade No. 2167, received with the proposal from the regional government dated March 2 of this year No. 1018, I have the honor to provide the following information about the military elder from the Kara-Kyrgyz, Shabdan Djantaev.

To clarify the origin of the influence exerted on the Kara-Kyrgyz by Shabdan Djantaev, whom Major General Baron Shtakelberg attributes to his outstanding noble status, it is necessary to familiarize oneself with the history of the existing manaphood in the Pishpek district, to which Shabdan also belongs.

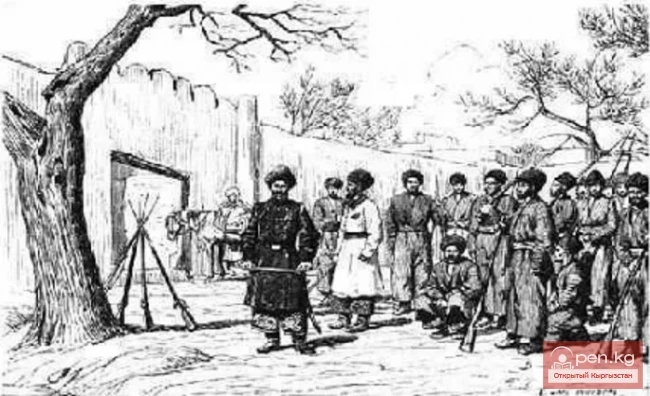

The Kara-Kyrgyz in this district are divided into the clans of Sultu, Sarbagysh, and Sayak. Each clan has its own manaps. The Sultu clan is the strongest, followed by Sarbagysh, to which Shabdan belongs. Each clan had several families of manaps, who during the Kokand rule constituted privileged estates, having the Kyrgyz of simple status completely under their control, who are still referred to as "bukara." The dominance of the manaps over the bukara was unlimited: they paid kalym for brides, showcased their bukara as prizes in horse races, and, with their own judgment, could take the lives of the guilty. At the head of all the manaps stood the Kyrgyz khan Urman, with very limited powers. The Kokand khan governed the manaps themselves, judging only those manaps considered equal among themselves; the wealth of the manaps was determined not only by the number of livestock but also by the number of bukara (slaves) and kul (bondservants). Among the prominent, the number of bukara was considered as follows: Djantay, Shabdan's father, had about 700 yurts; Khudoyar, the father of Sooronbay, had about 700 yurts; Djangarach, the father of Dikambay, along with his brother Sultanal, had up to 1000 yurts; Shamen, who is still alive, had up to 400 yurts; then among the smaller manaps, there were up to 300, 200, 100, and even as few as 10 yurts. Thus, during the khanate, the manaps were very powerful. All the aforementioned Kyrgyz are now alive and were young men during the dominance of their fathers, and since the manaphood was hereditary, the people still cannot change the deeply rooted consciousness of the superiority and power of the manaps, who still take every measure to preserve their preeminent position among the Kyrgyz. On this basis, the authority of the manaps in the eyes of their bukara is indeed great, and they must be taken into account at every step. However, on the other hand, the manaps were equal among themselves, and the influence of each extended only over their own bukara. Djantay, Shabdan's father, and Shabdan himself were merely members of the manaphood and did not occupy a preeminent position. On the contrary, Djangarach from the Sultu clan, whose son Dikambay is now in the Sokuluk volost, was considered older and more respected than Djantay, while in the Sarbagysh clan, Khudoyar, the father of Sooronbay, who is associated with the Tynaev volost, was considered more influential and noble than Djantay and Shabdan, while the former Kara-Kyrgyz khan Ormon undoubtedly stood above all.

Meanwhile, the children of Djangarach, who did not manage to rise in Russian service, are now considered ordinary manaps, influencing only a few hundred Kyrgyz in their Sokuluk volost, while the children of Khan Ormon, who rebelled against Russia, fled to Kashgar and were ruined with their yurts, now have about 50 yurts of supporters, former slaves, and cannot achieve a position higher than that of a fifty-man in the Sarbagysh volost, where Shabdan lives. Sooronbay Khudoyarov is still considered equal to Shabdan but is less influential due to a lack of energy. Therefore, I take the liberty of denying the assumption of the commander of the Transcaspian Cossack cavalry brigade, expressed in a letter dated December 21, 1895, No. 2167, that Shabdan Djantaev, due to his outstanding noble status among his kin, is still compelled to bear significant expenses for the needs of the people and the government according to the custom accepted among the Kyrgyz. As described above, other manaps equal to Shabdan and even of higher nobility now live as ordinary Kyrgyz and are not compelled to spend on the needs of the people, helping as much as they can according to the existing customs among the Kyrgyz, alongside others. Therefore, Shabdan Djantaev's influence is primarily based on his personal merit before the Russian government, which I am not competent to judge, and which alone should be evaluated in deciding the issue of increasing his pension.

Furthermore, although Shabdan's nobility is significant, he has gained preeminence among the Kyrgyz through his intelligence and cunning. During the subjugation of the region to Russian authority, he immediately understood that their manap rule had come to an end, and therefore, to rise under the new circumstances, he was more diligent than all others in providing services to Russia, which then provided him with assistance. He extended his policy further, solidifying his position through significant connections, as evidenced by the letters of Major General Baron Shtakelberg and the commander of the troops of the Transcaspian region.

He has other influential acquaintances that the Pishpek district officials would not even dare to dream of, and therefore they must meet with Shabdan not as with other manaps. The people see this and consider Shabdan strong with the Russian government, and therefore authoritative.

If it were not for such merit before Russia, he would be just another manap like many others in the Pishpek district. A small example can confirm this. Before the appointment at the end of last year of a deputy for the sacred coronation of Their Imperial Majesties, it was initially unknown to the people that the deputy from the people had to travel at his own expense, and therefore there was a proposal to collect 20 kopecks from each yurt for the deputy's expenses. When the question of appointing a person arose, many wanted to nominate their own.

Then the Kyrgyz decided that there were many equals among them and everyone wanted to be at the coronation, but only Shabdan was more deserving than all of them, and therefore it was decided to elect Shabdan. Here, he was given preference precisely on the basis of his merits and also because, as the Kyrgyz said, "he knows many good gentlemen, with whom he knows how to conduct himself." All of Shabdan's strength lies precisely in this. The Kyrgyz are like children; it is not difficult to throw dust in their eyes. I saw how Shabdan, during a public holiday, slaughtered several heads of livestock daily for three days and treated the Kyrgyz, who came to him in crowds to pay their respects. I also saw how during public games, Shabdan threw ruble notes to the Kyrgyz who distinguished themselves in competitions and then tossed handfuls of silver into the crowd, laughing like a child at the crowd pressing around the money. Such antics, aimed at effect, indeed cost him dearly, but there are hardly grounds to support them.

It is especially uncomfortable for me to support his authority given his developed passion for various ishan and hodja, for whom he collects enormous donations from the people in livestock. A year or so ago, I raised the issue of teaching the Kyrgyz Russian literacy among the honored individuals; many responded sympathetically and did not set any conditions, while Shabdan directly conditioned that these schools be at mosques and that children must be taught the Muslim religion. In view of this, this year I began the matter of schools with other Kyrgyz, and when everyone agreed, it was already embarrassing for Shabdan to lag behind the others, and he joined in.

None of his sons have been taught Russian literacy, while one of them received higher Muslim education at the Andijan madrasa.

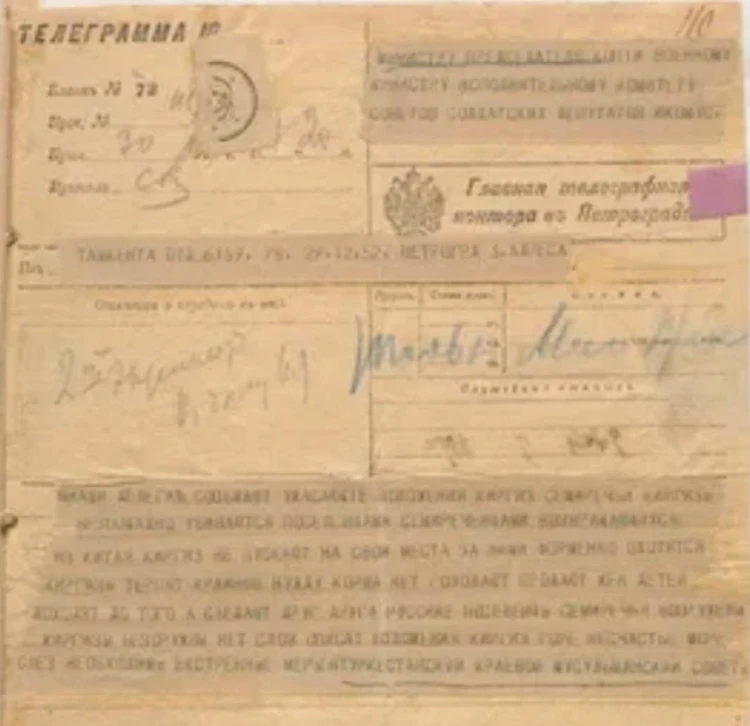

Dispatch to the military elder Shabdan Djantaev

Read also:

Report of the Chief of the Pishpek District to the Semirechensk Regional Administration on the Place and Role of Shabdan Jantaev Among the Kara-Kyrgyz. Part - 2

Part - 2 Having thus clarified the essence and origin of the influence that Shabdan Zhantayev...

Opening of the Consumers' Society in the city of Pishpek. Documents No. 23 - No. 24 (August 1897)

REPORT OF THE HEAD OF THE PISHPEK DISTRICT TO THE MILITARY GOVERNOR OF THE SEMIRECHEN REGION ON...

Investigation into the complaint of residents of Sarbagyshevskaya Volost regarding the oppression by the Janatayevs.

STATEMENT FROM ONE OF THE COMMUNITIES OF KIRGIZS OF THE SARYBAGYSHEVSKAYA VOLOST TO THE MILITARY...

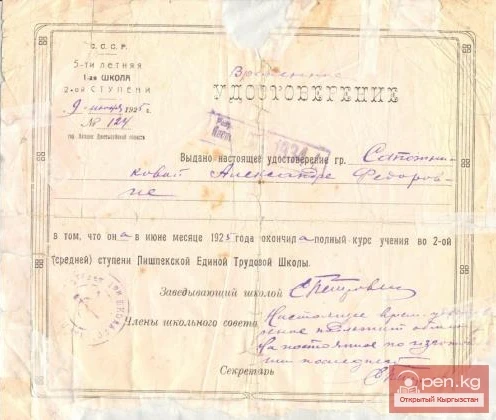

Events at the Bishkek City Men's School. Document No. 20 and No. 21 (1896 - 1897)

REPORT OF THE PISHPEK CITY ELDER TO THE SEMIRECHEN REGION ADMINISTRATION ON THE EVENTS HELD TO...

Hero Demanded by the Era. Part 2

The Influence of Shabdan Jantayev among the Kyrgyz of the Semirechye Region An analysis of the...

Report on the Behavior of Shabdan Djantaev During the Unrest

REPORT OF THE TOKMAK DISTRICT CHIEF TO THE ACTING MILITARY GOVERNOR OF THE REGION ON THE RIOTS...

Opening of the Pishpek Charitable Society. Document No. 22 (March 1897)

REPORT OF THE HEAD OF THE PISHPEK DISTRICT TO THE MILITARY GOVERNOR OF THE SEMIRECHENSKAYA REGION...

Request of Shabdan Jantaev for the release of the prisoner moldo Mamyrbay Kuatbekov

STATEMENT OF MILITARY SERGEANT SHABDAN DJANTAEV AND MANAP OF TOKMAK DISTRICT SAURAMBAI KHUDOYAROV...

Report on the Arrival of Representatives of the Rebel Kokand Kyrgyz in the City of Verny and the Attitude of the Turkestan Administration Towards the Rebels

REPORT OF THE ACTING TURKESTAN GENERAL-GOVERNOR, LIEUTENANT GENERAL G. A. KOLPAKOVSKY TO THE...

Reports of the Chief of the Pishpek District. Documents No. 15 - No. 18 (1891 - 1894)

REPORT OF SURVEYOR DMITRIEV TO THE MILITARY GOVERNOR OF THE SEMIRECHYE REGION ON ALLOCATED PLOTS...

Report by Kolpakovsky on the Arrival of Representatives of the Rebel Kokand Kyrgyz to the Russian Authorities

REPORT OF THE ACTING TURKESTAN GENERAL-GOVERNOR LIEUTENANT GENERAL G. A. KOLPAKOVSKY TO THE...

Report of the Chief of Khojent District Baron N. Nolde to the Military Governor of Syrdarya Region Major General P. K. Eiler

REPORT OF THE HEAD OF KHOJENT DISTRICT BARON N. NOLDE TO THE MILITARY GOVERNOR OF SYRDARYA REGION...

Hero Demanded by the Era. Part - 4

Letter from Abdullabek Alimbek uulu to General Skobelev The actions of Shabdan the Hero and his...

Cover Letter to the Semirechensk Regional Administration. Document No. 28 and No. 29 (1901 - 1902)

COVER LETTER FOR THE SUBMISSION TO THE SEMIRECHENSK REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION FROM THE BISHKEK...

Hero Demanded by the Era. Part - 3

...the Kyrgyz must live together like bees in one hive... The political influence of Shabdan was...

Transfer of the Control Center from Tokmak to Pishpek. Documents No. 5-7 (May 1878 - February 1880)

REPORT OF THE HEAD OF TOKMAK DISTRICT TO THE MILITARY GOVERNOR OF SEMIRECHENSKAYA REGION ON THE...

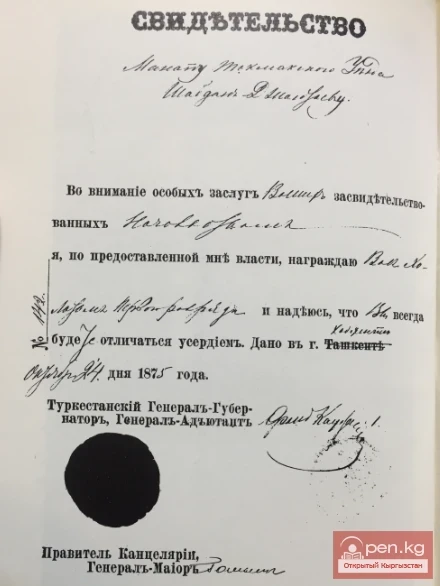

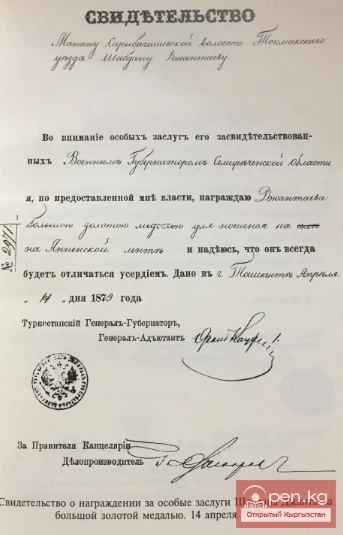

Awards of Shabdan Djantaev

CERTIFICATE OF AWARD OF MANAP OF TOKMAK DISTRICT SHABDAN JANTAEV WITH THE MEDAL FOR THE CONQUEST...

Agenda for the Senior Officer Shabdan Djantaev

SUMMONS TO SENIOR SERGEANT SHABDAN DJANTAEV TO SEND THE ONE HUNDRED RUBLES DONATED BY HIM ON THE...

Report of the Chief of the Pishpek District Talizin to the Semirechye Military Governor

City of Pishpek November 10, 1894. Herewith I am returning three petitions entrusted by the...

Petition for the Satisfaction of A.M. Fetisov's Request. Documents No. 13 and No. 14 (January 1891)

RESPONSE OF THE STEPPE GENERAL-GOVERNOR TO THE REQUEST OF A.M. FETISOV SUBMITTED FOR HIS...

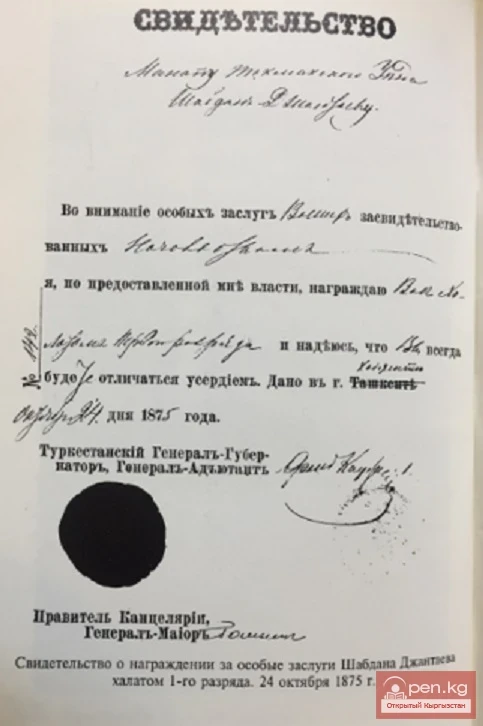

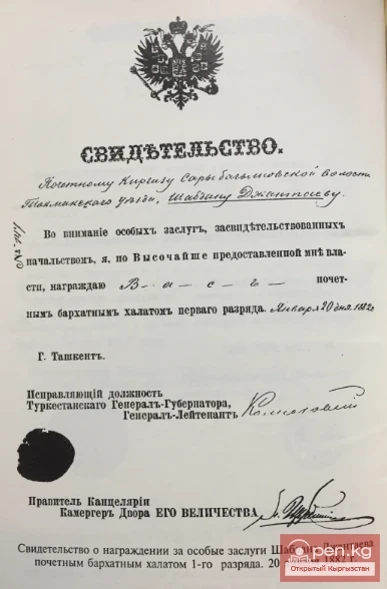

Certificate of Awarding Shabdan Djantaev the First-Class Robe

CERTIFICATE OF AWARD FOR SPECIAL MERITS OF MANAP OF TOKMAK DISTRICT SHABDAN JANTAEV WITH A...

The Wealthy Social Layer Among the Kyrgyz in the Late 19th Century

Bais, Biis, and Manaps The measure of wealth and the main equivalent in trade and economic...

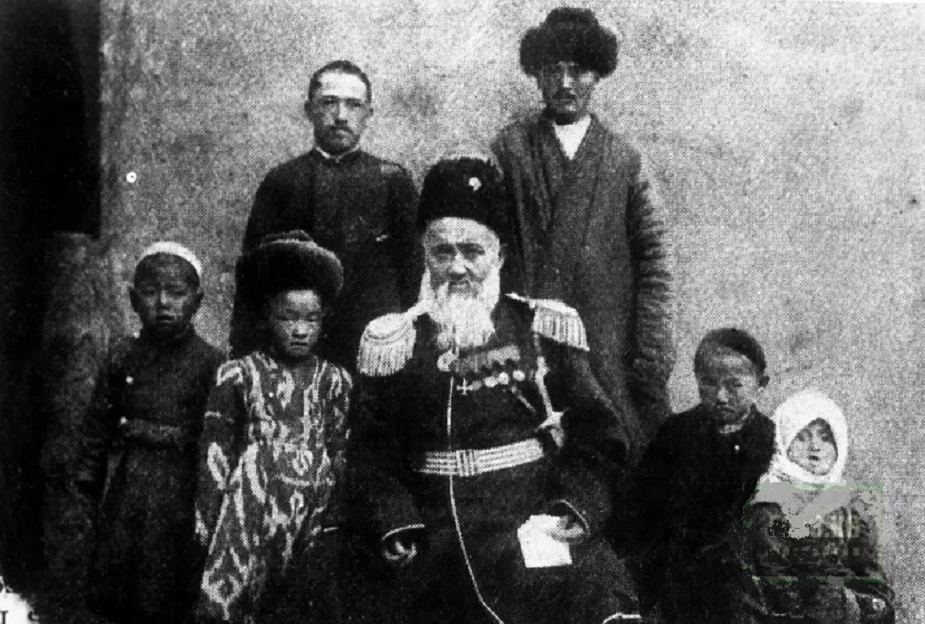

Service Record of Police Senior Officer Shabdan Djantaev

January 30, 1888. 1. Rank, first name, patronymic, surname, position, age, religion, distinctions,...

Report to the Governor of the Semirechye Region on the Extraordinary Congresses of Susamyr and Sonkul

REPORT OF THE SENIOR OFFICIAL FOR SPECIAL ASSIGNMENTS OF ARTILLERY CAPTAIN REINTAL TO THE MILITARY...

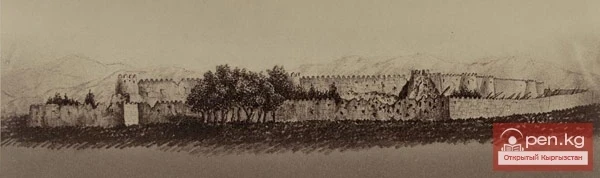

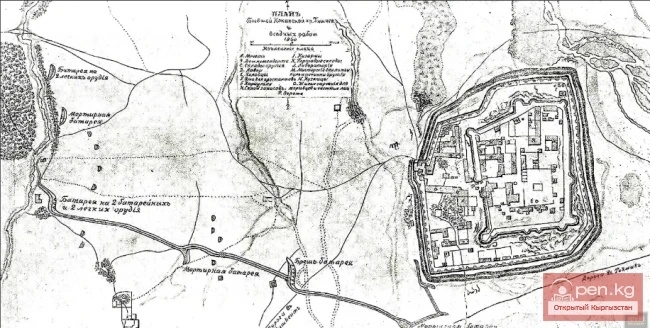

From the Kokand Fortress to the City of Frunze. The Kokand Fortress

FROM THE KOKAND FORTRESS TO THE CITY OF FRUNZE KOKAND FORTRESS In the second quarter of the 19th...

Treaty of Friendship between the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs in August 1847

TREATY OF FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE MANAPS AND BIYS OF THE KYRGYZ AND THE SULTANS AND BIYS OF THE...

Protocols of the Meeting of the Pishpek Ugrrevkom in 1924. Documents No. 56 and No. 57

FROM THE PROTOCOL OF THE MEETING OF THE EXECUTIVE BUREAU OF THE PISHPEK UGORREVKOM OF THE...

Instruction to the Military Governor of the Semirechye Region from the Steppe General Governorship

ORDER TO THE MILITARY GOVERNOR OF THE SEMIRECHENSKAYA REGION FROM THE STEPPE GENERAL-GOVERNORATE...

Social-Professional Structure among the Kyrgyz

Social and Professional Structure. The Kyrgyz did not have closed caste associations, typical of...

The Siege of the Pishpek Fortress

Plan of the siege of the fortress of Pishpek by Russian troops The Capture of Pishpek In October...

Awarding Shabdan Jantaev a robe for special merits

CERTIFICATE OF AWARD FOR SPECIAL MERITS OF HONORARY KYRGYZ SHABDAN DJANTAEV OF TOKMAK DISTRICT...

Decisions on the City Public Bank in the City of Pishpek. Documents No. 25 - No. 27 (1899 - 1900)

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE SEMIRECHYE REGIONAL AUTHORITY ON MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS REGARDING THE...

Once Again About Shabdan

The history of a country is a delicate matter. Here, a careless word is enough to sow...

Protocols, letters, resolutions in 1925 in the city of Pishpek. Documents No. 58 - No. 61

CIRCULAR LETTER OF THE REVOLUTIONARY COMMITTEE OF THE KYRGYZ AUTONOMOUS REGION TO ALL STATE...

Weather for March 15-17

A cold snap is expected in Kyrgyzstan from March 15-17 Unstable weather is expected on March 15:...

A Brief Chronology of Historical Events in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan - Chronology of Major Historical Events 400,000 years ago - The oldest Stone Age...

Document No. 4 (December 1877). Report of the Military Governor of the Semirechye Region to the Turkestan General Governor

REPORT OF THE MILITARY GOVERNOR OF THE SEMIRECHYE REGION TO THE TURKESTAN GOVERNOR-GENERAL...

Report of the Chief of Tokmak District. Document No. 12 (December 1890)

REPORT OF THE CHIEF OF TOKMAK DISTRICT ON THE INSTRUCTION OF THE MILITARY GOVERNOR OF SEMIRECHYE...

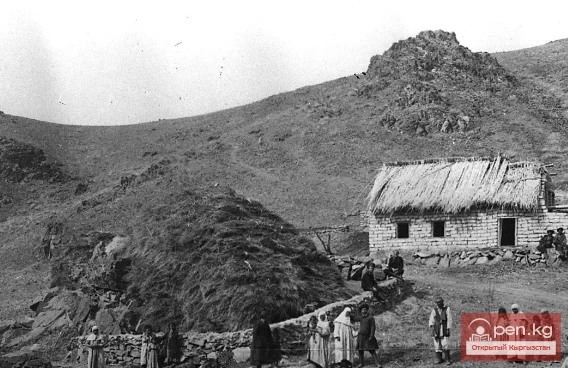

The 19th Century — A Century of Radical Change in the Lives of the Kyrgyz

Settlements and Permanent Housing The 19th century was a turning point in the life of the Kyrgyz....

Letter from the Commander of the Siberian Corps N.G. Ogarev to the Hero Batyr Tynaybiyev

LETTER FROM THE COMMANDER OF THE SIBERIAN CORPS N. G. OGAREV TO THE HERO ATAKE-BATYR TYNAYBIEV ON...

Generations of Kyrgyz and Kemkemchut

Excerpt from the work of Abu-l-Ghazi (1603—1664) — almost a retelling from Rashid ad-Din's...

Gerasim Alekseevich Kolpakovsky - the First Researcher of the Archaeological Mysteries of Issyk-Kul

General of Infantry Gerasim Alekseevich Kolpakovsky When recounting the lives of Russian military...