Life in the Regions: Face to Face with Death Every Day: The Story of Damira Naimanova Working in the Morgue of the City of Osh

With 12 years of experience as a junior staff member in the forensic department of the Osh regional bureau of forensic medical examinations, Damira participates in the process of handling bodies that come to her. She works with victims of traffic accidents, murder victims, suicides, and those who died under strange circumstances.

Her duties include receiving bodies, washing, cleaning, stitching, dressing in a shroud, and placing them in the refrigerator—all these tasks fall on the shoulders of one woman.

Damira was born in 1976 in the village of Japalak near Osh. She is married and has two children—a son and a daughter.

“Like many, I dreamed of going to Russia. But when the children started school, I needed to take care of them. So I stayed, and an acquaintance offered me a job here,” Damira recounts.

Initially, she worked as a cleaner in the forensic department, but soon began to participate in the main work. “When I was cleaning the offices, my colleagues would gather for tea, and I would ask, ‘Are you free?’ At that time, they could be carrying out a body. I waited, got used to it, sometimes helped, and soon it became ordinary work for me,” she notes, adding that she is not afraid of the dead: “They are scarier than the living.”

Damira remembers her first day at work when she first worked alone with a body: “A boy who died in an accident was brought to us. We carried out all the necessary procedures and handed him over to his relatives.”

She emphasizes that society often misunderstands the essence of forensic examination. “When they hear the word ‘examination,’ everyone immediately thinks of the morgue. But that’s just one part of the work. In our field, there are many departments—laboratories, histology, biology, and the department for injuries,” Damira highlights.

Once the body is delivered, the responsibility shifts to the experts and sanitary workers. “The police work ends at the delivery stage. We receive the body, and the investigator records the data in a log, indicating who delivered it and their signature,” she explains.

If relatives cannot be found, the body is placed in the refrigerator. “After receiving, we transfer the body to the autopsy room and lay it on the table. If a person has no relatives, we keep them in the refrigerator until the investigator provides the documents,” Damira adds.

Sometimes they also receive newborns who died shortly after birth. “There are cases when children who lived only two hours are brought in. Their father files for an examination, accusing the doctors of negligence,” she shares.

According to Damira, the number of suicides among teenagers sharply increased in September 2025. “Children born between 2000 and 2012, mainly in 2009 and 2010, began to hang themselves. Two to three bodies were brought at a time. There was even a girl born in 2011, as well as cases where children drank vinegar,” she recounts.

When 5 to 6 people die in a traffic accident, all bodies arrive simultaneously. “This is considered a mass arrival. We conduct autopsies, and sometimes the bodies are in terrible condition, with obvious injuries. Sometimes we have to restore their shape by stitching and wrapping tissues,” Damira explains.

Despite her experience, she admits that sometimes she cannot hold back her emotions. “When you see crying relatives, it’s hard to remain indifferent. Everyone has children, and your heart tightens. There are days when I cry too. Children who were raised with hope... sometimes I just step outside, reflecting on how it was meant to be,” she shares.

She explains how they determine the time of death by post-mortem stains. “Depending on the position of the body, stains form, and we determine how much time has passed since death by them,” Damira says.

Sometimes they receive bodies that have been lying for a long time. “Recently, a body of a man of Russian nationality was found near the airport—it was mummified. But regardless of the condition, we conduct an examination and place the body in a special bag,” she adds.

Relatives are shown the body only with the investigator's permission. “We can only release the body based on an identification document, and only with the investigator's permission,” Damira clarifies.

Unfortunately, very few people want to work in this field. “No one wants to go into this profession. We searched for employees but found none. If something happens in the districts, we go ourselves. Now I work alone throughout the Osh region,” she says.

Sometimes examining one body takes a significant amount of time. “If there are many injuries, it can take more than an hour. When bodies arrive daily, it is very exhausting. After the examination, we strictly follow all requirements,” Damira shares.

Recalling the pandemic period, she talks about the difficulties. “We worked in protective suits, examining those who died from coronavirus, taking samples, stitching, and washing bodies. The deceased had enlarged lungs, as if filled with pus. It was terrifying, but we continued to work,” she remembers.

Damira was also at the site of the tragedy in Oң-Adyre. “A mother and five children died there. We went out with an expert, examined the bodies, and brought them here. It was hard—how they lay, they burned. Relatives brought film, and we wrapped the bodies,” she recounts.

Sometimes additional permission is required to straighten limbs. “If they are stiff, we ask for permission on how to straighten them. Sometimes we have to cut to fit them in the shroud. The skin of burned bodies hardens,” Damira shares.

It is difficult for her when bodies remain unclaimed. “It’s good when relatives are found. But sometimes the body begins to decompose, and a smell appears. If no one comes forward within a month, we carry out a burial at the expense of the mayor's office,” she explains.

Openly discussing her financial difficulties, Damira admits: “The salary is small. My husband cannot work due to health issues, so I am the sole breadwinner. We have two school-aged children.”

Young people are not eager to enter this profession. “Now I do all the work alone—wrapping bodies, cleaning the premises, and transferring bodies to the refrigerator. Even students are afraid of this work. We offer them to do an internship, but they refuse. There is one resident, and sometimes I call him for help. He will become an expert in two years,” Damira concludes her story, facing death every day.

Read also:

Damira Amanovna Mamytova

Mamitova Damira Amanovna (1957), Doctor of Agricultural Sciences (1999) Kyrgyz. Born in the city...

Kasabolotova Damira Asekovna

Kasabolotova Damira Asekovna Applied artist. Born on June 21, 1963, in the city of Frunze. From...

Alymbaeva Damira Beishekeevna (1953)

Alymbaeva Damira Beyshekeevna (1953), Doctor of Medical Sciences (1997), Professor (1998)...

Nowruz is a bright and kind holiday that unites all of us, Kyrgyzstanis.

The Vice Prime Minister of the Kyrgyz Republic, Damira Niyazalieva, who is on a working trip to...

In Batken, a 35-year-old woman died after giving birth

Tragedy in Batken: 35-year-old woman died after childbirth. Turmush — A tragedy occurred in Batken:...

Damira: Society Has Not Advanced in Knowledge About HIV as Much as Medicine Has

In Kyrgyzstan, the Republican Center for the Control of Hematogenic Viral Hepatitis and HIV...

Damira Omutaevna Egimbaeva

EGIMBAEVA Damira Omutaevna...

Memorial and Cultural Complex "Kurmanjan Datka" Transferred to the State

On April 10, during a working trip to the Issyk-Kul region, the Vice Prime Minister of the Kyrgyz...

A Kyrgyz woman was swept away by a wave in Malta. She died.

Information about the tragedy appeared on social media when a relative of the deceased reported...

Life in the Regions: In a Batken Store, Seeing a Nurse in Different Clothes, She and Her Husband Were Refunded for Their Purchase

Inabat Abdullaeva, a resident of Batken, has dedicated herself to the nursing profession for over...

Life in the Regions: At 90, She Has 178 Descendants - The Incredible Story of Talas Resident Saty Eshalieva

In the village of Zhon-Aryk, located in the Talas region, lives 90-year-old Saty (Sakish)...

Life in the Regions: Gülbayra Nogoybaeva Works in a Job Where She Used to Run from Drunks and Feared It Was Like Going to War

Gulbaira Nogoybaeva, a 62-year-old resident of Kara-Kul, has been working in the healthcare sector...

Relatives of the 32-year-old woman from Aksy are asking for an objective investigation into her death

In the Aksy district, a 32-year-old woman was found dead. Her body was discovered on November 4 in...

Life in the Regions: 47 Years as a Teacher and No Change — Natalia Solonitsyna from Kara-Balta Shared the Secret of Youth

Natalia Solonitsyna from the city of Kara-Balta has been working as a teacher for 47 years. In a...

In Batken, a pregnant woman and her unborn baby died

A tragedy occurred in Batken: a pregnant woman died in a local hospital without regaining...

Mirgul from Osh has an unusual surname: People don't believe her at first.

35-year-old Mirgul from Osh has the surname Apendieva, which often becomes a source of...

Life in the Regions: Gulira Asyranova Swapped Her Pointer for Toys and Fell in Love with Her Job

A 42-year-old resident of the city of Talas, Gulira Asyranova, works as a kindergarten teacher. A...

Our People Abroad: For Gülzhamal Kadyrkulova, the separation from her children has become the heaviest price of earning a living in Russia

In the "Our People Abroad" section, we will tell the story of Gülzhamal Kadyrkulova. The...

Beauties in Epaulettes: Aliya Sooronbaeva Met Her Future Husband at the Police Station

Aliya Sooronbaeva from Talas found her better half at work. The resident of the village of...

Life in the Regions: The Street Where Only Girls Are Born — The Story of a Heroine Mother from Talas

39-year-old Munduz Kudaybergenova, living in Talas, has become a true heroine among mothers. A...

Bakhityar Nematov Appointed Head of the Railway Station in Osh City

Bakhtiyar Saytmuratkhanovich Nematov has been appointed as the head of the Osh railway station....

Life in the Regions: Sheep Started Biting the Teacher as She and Her Husband Made Their Way to the Most Remote School in Kyrgyzstan in 40-Degree Frost

Zhyldyz Abdykerimova, a teacher with over 23 years of experience, works at one of the most remote...

In Thailand, a woman "rose from the dead" five minutes before cremation

An unusual case occurred in Thailand, where a 65-year-old woman "rose from the dead" just...

Unusual Names: A Resident of At-Bashy Was Named After a River in Russia and a Successful Woman

The new heroine in our "Unusual Names" section is Aleiy Mongoldorova, residing in the...

In a car accident, ophthalmologist Gulnura Maatkerimova died.

In the Naryn region, as a result of a traffic accident, ophthalmologist Gulnura Zholdubaevna...

"Resuscitation - the Last Hope": Why Are Doctors Leaving Naryn?

Zhyrgalbek Aaliyev, a doctor with 37 years of experience, works in Naryn. For eight years, he held...

In Manas, a 31-year-old woman gave birth to triplets

In the maternity ward of the Jalal-Abad region, located in Manas, an amazing event occurred on...

Life in the Regions: Teacher from Ak-Suu R. Moldokerimova Provided Examples of Effective Student Learning

Rakima Moldokerimova, an educator with 40 years of experience and a physics teacher at the M....

In the Sokuluk District, a woman died after being beaten. Her husband has been detained.

According to information provided by the press service of the Main Internal Affairs Directorate of...

The relatives of the woman who died in Aksy appealed to Kamchybek Tashiev.

The family of a 32-year-old woman who tragically died in the Aksy district of the Jalal-Abad...

Amazing coincidence: 42-year-old Elizat Nurseitova gave birth to triplets on her birthday

A resident of the Ak-Talinsky district in the Naryn region, Elizat Nurseitova, who gave birth to...

Life in the Regions: Bakmurat Sapiraliyev from Talas was prophesied to be immobile, but he spoke and walked thanks to faith

In Talas lives 15-year-old Bakmurat Saparliev, who, despite being diagnosed with cerebral palsy...

Unusual Names: A Resident of Osh Was Named After a Flower That Looks Like a Lion's Paw

Turmush continues to tell the stories of the residents of Kyrgyzstan with original names. According...

Life in the Regions: M. Kalmyrzaeva from Bakai-Ata Started Her Own Home Business

34-year-old Madina Kalmyrzaeva, who lives in the village of Keng-Aral, has started making sweets to...

36-year-old Gulnara Junusova gave birth to her fourth child on New Year's Day

On December 31, 2025, on New Year's Eve, 36-year-old Gülnaara Junusova from the village of...

Life in the Regions: Those Who Watched Aizhan Taitakova in Childhood Predicted Who She Would Become in the Future

Gathering and drying medicinal herbs in her childhood, Aizhan Taitakova sparked assumptions among...

Life in the Regions: In the East of Issyk-Kul, a Mother of Many Dreamed of Becoming a Doctor but Became an Astrophysics Teacher

In the Ak-Suu district of the Issyk-Kul region, in the village of Teploklyuchenka, lives Aysuluu...

District No. 3. Names of the 6 registered candidates for deputies of the Jogorku Kenesh

The Central Commission for Elections and Referendums has begun the registration of citizens wishing...

A 40-Year-Old Woman Has Died in the City of Manas

A 40-year-old woman was found dead in Manas, hanged in her home. According to information received...

A man suspected of murdering an acquaintance has been detained in Kyzyl-Kiya.

The incident occurred on November 18 in a dormitory room in one of the residential buildings in the...

Life in the Regions: A 74-Year-Old Teacher from Talas Ran a Marathon, and Once Taught Troublemaker Teenagers Five Years Younger Than Her

Meizbubu Myrsalieva, a 74-year-old resident of the Talas region, demonstrated remarkable endurance...

Unusual Names: The Professor Rushed into the Ward, Expecting to See His Student Love Who Had a Spring Name

Among the participants of the "Unusual Names" section is 46-year-old Zhashylgul...

Life in the Regions: Elzat, despite the problem that made her cry, has mastered horseback riding and is engaged in stunt work.

Elzat Juzupbek kyzy, a 33-year-old stuntwoman, has had a passion for horses since childhood and...

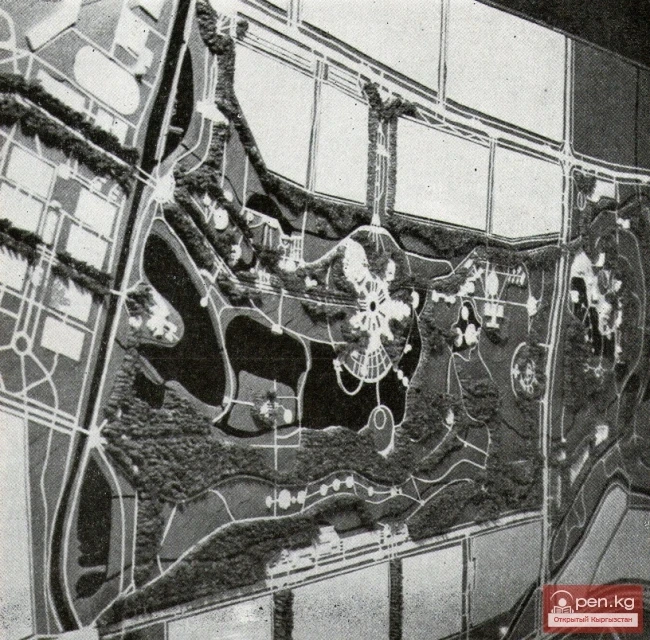

Caves of Kyrgyzstan

Caves of Kyrgyzstan Caves are rightly called the cradle of humanity. Primitive people took shelter...