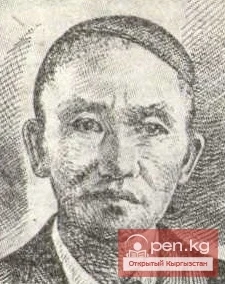

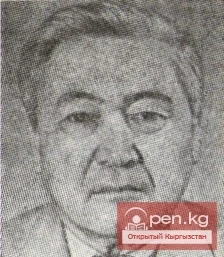

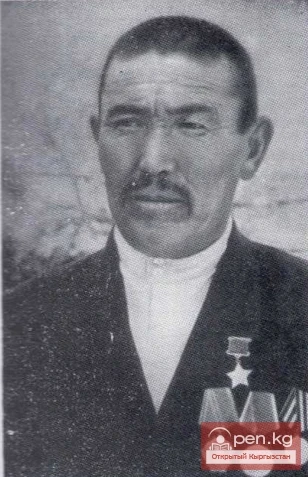

Hero of the Soviet Union Jarkymbaev Kazak

Kazak Jarkymbaev was born in 1911 in the village of Tashtak, Issyk-Kul region of the Kyrgyz SSR, into a family of a poor peasant. He was Kyrgyz. Orphaned at the age of five, he began working early. Since the time of collectivization, he worked in a collective farm.

In November 1941, he was drafted into the Soviet Army. Guards senior sergeant. Gun commander.

During the Great Patriotic War, he fought as part of the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian fronts. He distinguished himself in the battle for the Dniester bridgehead.

On March 24, 1945, for his feat, valor, and heroism, he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

After the war, K. Jarkymbaev returned to his native collective farm and continued to work. He died in 1969.

The name of the Hero is carried by the village of Jarkymbaev (formerly Kamenka) and the secondary school of this village.

IRON RESILIENCE

Could the shepherd Kazak, who grew up without a father and mother in the mountain aul of Tashtak in the Issyk-Kul region, have thought that just a few years later, his fellow villagers would unanimously elect him as the chairman of the collective farm? Of course not. He diligently studied at the school, which would later bear his name, and during the holidays, he eagerly learned the ancient science of sheep herding. Thus, his adolescence and youth passed in his beloved activity.

The war broke out. In the winter cold, Kazak was sent off by his fellow villagers along with other draftees to the front.

— Today we send our sons to the great battle against the treacherous enemy,— said an elderly elder at a brief meeting. — And with each passing day, fewer and fewer hardworking horsemen remain in the aul, all the burden of work falls on the shoulders of women and teenagers. But we will endure all hardships, we will not flinch before any trials. We will do everything for you, our dear children, we will clothe you and feed you, and warm you with our letters, just fight fearlessly and return victorious.

This charge Jarkymbaev carried throughout the war.

...No matter how much he mentally prepared for his first battle, no matter how hard he tried to overcome his anxiety and shyness before the unknown, he could not conquer it. At dawn, our artillery began shelling enemy positions. The company commander gave the order to prepare for battle. “Now, we will shoot, they will shoot at us too. They might hit me. What will happen to me? Am I really afraid?”— Kazak asked himself. And memories of childhood surfaced in his mind.

His native aul, the air filled with the scent of blooming gardens, the clear spring where he ran for crystal water with a sharp-eyed neighbor girl. “They want to take all this away from us. They burn, rape, kill innocent people. They kill just because they came to kill. Well, let’s see how they like our lead,”— he angrily pulled the bolt of his rifle.

From somewhere on the left came the sharp command: “To the attack, forward!” Kazak rushed too hastily onto the parapet, stumbled, and fell. Cursing, he jumped up. The guys from his platoon were already about ten steps ahead. They were running toward the enemy trenches, taking cover behind tanks. Kazak followed, catching up with his comrades. Figures in mouse-colored overcoats were jumping out of the enemy trenches and fleeing. Quickly aiming, Kazak, like his comrades, fired bullet after bullet at the retreating enemy. “Here you go, here you go,”— he kept repeating, and he could have pursued the enemy for a long time, until complete exhaustion, but he heard the order to secure the captured trenches.

Later he would understand that there was actually no battle for him. The Germans could not withstand the tank attack and fled from our armor. But he was now a battle-hardened soldier, preparing more calmly for the next fight.

Some time later, while retreating with a handful of comrades, Kazak found himself at our artillery position.

One gun was destroyed, the other was intact. Artillerymen lay covered by the explosion. Together they managed to load the gun, aiming it at the dense group of fleeing fascists in the ravine. The shot was successful. The infantry fired until they ran out of shells, greatly assisting the battalion that counterattacked and regained the lost line.

After the battle, Kazak and his comrades, who showed resourcefulness and courage, were sent to junior commander courses. After their completion, in 1943, senior sergeant Jarkymbaev was appointed commander of an anti-tank gun. His new place of service was the 95th Guards Poltava Red Banner Division of the 3rd Ukrainian Front.

With each passing day, the combat training of the junior commander strengthened, he became more confident in handling the weapon, and the shells fired from his forty-five landed more accurately. In April 1944, the unit where Kazak served reached the Dniester.

The fascists clung to every piece of land, and here, at this natural barrier, they hoped to establish themselves for a long time.

The night was dark, the sky was gloomy and, as it seemed to the soldiers, harsh. The next morning, a fierce battle awaited.

The crossing to the Dniester bridgehead captured by the advanced units began. Jarkymbaev's crew, along with the forty-five, crossed quickly and without fuss. The company that Jarkymbaev's crew was to cover went around the Moldovan village abandoned by the enemy from the north and soon took up defensive positions.

The fighters, having quickly fortified themselves with dry rations, began to dig trenches. Kazak chose a height two hundred meters east, marked on the field map as “164.4”. They dug a trench near the old anti-tank ditch.

From both sides, illuminating rockets soared into the sky, and from time to time, bursts of machine-gun and automatic fire could be heard. Before dawn, everything fell silent. As dawn began to break, the artillery spoke. A messenger from the company commander ran in, delivering a message about a possible enemy attack and an order to hold out until the last shell, at any cost not to allow the fascists to push our troops back.

The messenger had not taken twenty steps when fascist bombers appeared in the sky. They lined up in their favorite “carousel,” heavy bombs began to fall... “Ah, the anti-aircraft gunners, we didn’t have time to cross over,— Kazak lamented,— we could have given them a taste.” But as if something broke in the “carousel,” it fell apart, the “Junkers” began to head west at low altitude. And from above, our “Yaks” swooped down on them. Kazak did not manage to watch the air battle: fascist tanks crawled out from behind a hill, with automatic gunners following behind them.

The direction of the attack chosen by the Germans was correct. They advanced on the left flank of our defensive positions. And with numerical superiority and tank support, they would surely have succeeded if it were not for Jarkymbaev's gun. Kazak immediately understood all the advantages of his position — the gun could strike the attacking fascists from the flank.

— Now the main thing is not to panic,— he told his fighters. — As you can see, the tanks are presenting their sides to us, we need to make as many shots as possible, accurate shots, before they can reorganize. And not a step back!

The crew commander ordered the fighters to take their places, and he himself took aim. Driver Kazakov delivered a new batch of shells and reported that the horse was killed. “But don’t spare the shells, commander,— he said,— I will carry them on my shoulders myself.” Letting the tanks get closer, the senior sergeant calmly took aim. With the first shot, one of the tanks was hit. Another one caught fire, the chain of automatic gunners lay down, but the fascist tanks were still advancing. “It’s okay, we have a good treat for the automatic gunners — fragmentation shells, right now the main thing is the tanks.

Shell! — Kazak urged the fighters. He shot without a miss. Only in two nearby tanks did they manage to realize that they were being fired upon from the flank. “The Tigers turned sharply, presenting their sides to our infantry. From the trenches, the reports of anti-tank rifles rang out. The armored attack faltered.

And Kazak was already firing at the automatic gunners with fragmentation shells. In the flat plowed field, there was nowhere to hide. The fascists fled, long machine-gun bursts pursued them.

But the battle was just heating up. The tanks went into the attack again, and self-propelled guns joined them. This time the spearhead of the attack was aimed at height “164.4”. And again Kazak rejoiced at the well-chosen position. The fascists could hardly see his gun, but from the height, everything was clear to him. The shells from the forty-five landed accurately. He set fire to the lead “Tiger” that tried to bypass the anti-tank ditch, and a self-propelled gun caught fire. And the second attack faltered.

Our stormtroopers finished off the retreating enemy.

Only by evening did the fascists recover from their defeat. And, receiving reinforcements, they again climbed the height. The enemy infantry approached from all sides. The positions of the brave warriors were bombed by stormtroopers. But Kazak Jarkymbaev acted accurately, skillfully firing shell after shell. The loader Yuldashev was severely wounded.

Kazak was also hit by a fragment, but he kept shooting. Bombs exploded nearby. Shrapnel, ringing, struck the shield, the barrel. The battle lasted until dusk. The “Malyutka,” as the soldiers affectionately called the gun, worked flawlessly until the last enemy attack faltered. The Germans could not break the iron resilience of the guards. The height stood firm, and in the morning reinforcements arrived.

For this feat, Kazak Jarkymbaev, our compatriot, was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union by the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on March 24, 1945.

Then there were new battles. The soldier from distant Kyrgyzstan marched westward. Through hardships and the bitterness of losses, through leaden rains, he marched toward Victory. And he met it in Germany.

With honor and numerous awards, the fearless warrior returned to his native land. And his fellow villagers elected him chairman of the collective farm. In peaceful labor, as in battle, he was tireless, resourceful, and did not spare himself. K. Jarkymbaev passed away in 1969.

Grateful fellow villagers named their village Kamenka after him, now it is Jarkymbaev.

I. MAMBETKAZIEV