This topic is a consequence of institutional failures and geographical fragmentation.

Historians assert that the division into north and south in Kyrgyzstan became relevant only during the Soviet period. Prior to that, Kyrgyz people were not divided into southerners and northerners, as they were under the rule of various states, such as the Kokand Khanate, the Bukhara Emirate, and the empires of Russia and China. With the formation of a unified Kyrgyzstan in the form of the Kara-Kyrgyz Autonomous Region, the split into south and north began, leading to the relocation of personnel between regions. To undermine the power of the manaps, the Bolsheviks relocated southern manaps to the north and northern ones to the south, depriving them of support and influence. This contributed to their loss of power, and the manaps yielded it to the Bolsheviks. Upon learning of this, the Bolsheviks began exiling other population groups, trying to control the situation in this way. This practice is still relevant today, as there is an opinion that mixing residents from the north and south can eliminate tribalism. However, the root of the problem lies in the long process of forming the Kyrgyz nation, which is still not complete and was not resolved during the socialist construction period.

Today, the division of Kyrgyzstan into "North" and "South" is one of the most persistent themes in the socio-political life of the country. It is not just a geographical reality, but a complex socio-political phenomenon that has influenced personnel policy, resource distribution, and the perception of Kyrgyz people towards each other for many years. Unlike interethnic conflicts, the issue of "northerners" and "southerners" represents intra-ethnic regional patronage, which is not enmity but rather a consequence of institutional failures and geographical fragmentation.

First. What is the nature of this phenomenon? Why has patronage become a "protective mechanism" for the Kyrgyz?

To understand the solution to this problem, it is important to abandon moralizing regarding regional elites and recognize the functionality of patronage. During the weakness of state institutions in the 1990s and 2000s, regional ties became the only functioning social lift and guarantee of survival. A "local" official from the same region was perceived not as a corrupt individual but as a protector capable of helping with road construction or employment.

The main idea here is clear: patronage acts as a "protective mechanism" that is activated in conditions where the state does not fulfill its functions. As soon as institutions begin to operate impartially, the need for a "regional roof" disappears.

Second. What is the strategy for "healing" this problem?

Experts propose a pragmatic approach that is far from populism. The solution lies in creating conditions under which regional identity will cease to be a political and economic resource. This means that appointments and personnel replacements will not depend on regional origin, which has been observed throughout the Soviet period and in the years of independence.

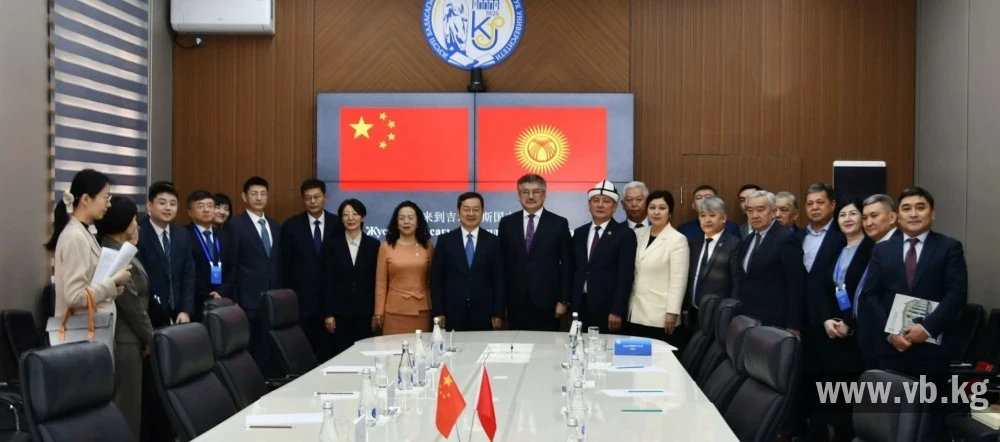

a) One of the steps should be to create infrastructure that connects the nation. For example, the construction of an alternative "North-South" road and new railway lines is not only a logistics issue but also the foundation for psychological unity. Reducing travel time between Osh and Bishkek and lowering transportation costs will promote the growth of interregional marriages, trade, and tourism. People stop perceiving each other as abstractions. Therefore, it is necessary to maximize the opportunities provided by the construction of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway to connect the regions.

b) Economic decentralization and moving away from the "Bishkek pie."

Competition for resources increases when they are concentrated in one place (Chui Valley). The development of new centers in Batken, Talas, or Naryn will reduce pressure on the capital and eliminate reasons for the elite to demand "compensation" for their region's underdevelopment. Creating jobs locally reduces the level of internal migration and, consequently, tension in densely populated cities.

c) Reform of personnel policy. Transition to the principle of meritocracy (the rule of the best).

The key idea is to replace regionalism with the principle of competence. As long as public service is perceived as a way to "provide for one's own," the country will remain divided. Implementing transparent competitive procedures based on personal merit will gradually reduce the significance of the question "whose are you?" When professionals, rather than clan affiliates, are appointed to key positions, citizens will lose their sense of regional injustice.

Third, it is necessary to define a time horizon.

In response to the question "How long should we wait for the disappearance of patronage sentiments?" the experience of other countries provides an honest answer: patronage will never completely disappear (as in any other country in the world), but its acute phase may weaken over 20-40 years (one to two generations).

· Change of elites. The political class that has grown in independent Kyrgyzstan and is integrated into global processes is less inclined to play on "regional cards." For modern businesses or IT specialists, outdated clan divisions become a burden.

· The process of urbanization is actively ongoing, creating a "melting pot." Bishkek and large cities act as natural neutralizers. Children of migrants from the regions, studying in the same schools and working in the same companies, form a new, supra-regional identity.

Fourth, demystification and a unified cultural code are required.

An important aspect is debunking the myth of "different peoples." The cultural, linguistic, and religious unity of Kyrgyzstanis is about 95%. Differences in dialects or culinary preferences (for example, different ways of preparing pilaf) should be perceived not as fault lines but as subjects of cultural exchange.

In this context, domestic tourism and the creation of a common information space play a significant role. When southerners visit Issyk-Kul and northerners visit the walnut forests of Arslanbob, the regions cease to be foreign to each other.

In conclusion.

The "North-South" problem in Kyrgyzstan can be resolved not through prohibitions and slogans, but by creating effective linking mechanisms: transport arteries, fair economic lifts, and impartial state institutions. The state must ensure equality for all, and then the need for "one's own" will disappear on its own. The main thing is the political will of the elites to start this process and not to parasitize on regional division forever.

Ilyas Kurmanov, Doctor of Political Science

Photo www