Deforestation Forces Mosquitoes to Switch to Human Blood

This change in behavior could lead to an increased risk of spreading dangerous viruses such as dengue and Zika.

As the area of the Atlantic Forest shrinks, mosquitoes are increasingly turning to humans as their primary source of blood. This shift may accelerate the spread of mosquito-borne diseases and increase the vulnerability of local communities to disease outbreaks.

The Atlantic Forest, which stretches along the Brazilian coast, is famous for its rich biodiversity, including hundreds of species of birds, mammals, reptiles, and fish. However, a significant portion of this biodiversity has already been lost, as human activity has reduced the forest to one-third of its original area.

With the deepening of human impact on previously untouched ecosystems, wildlife is being displaced, and mosquitoes, which once fed on various animals, are now increasingly seeking food among humans, as shown by the study published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

“We demonstrated that the mosquitoes we captured in the remnants of the Atlantic Forest primarily prefer humans as a food source,” said lead author Dr. Jeronimo Alencar, a biologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro.

“This is of great significance, as in an ecosystem like the Atlantic Forest, which is home to many species of vertebrates, a preference for humans increases the risk of pathogen transmission,” added co-author Dr. Sergio Machado, a researcher in microbiology and immunology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

To study the dietary preferences of mosquitoes, researchers set up light traps in the reserves of Sitio Recanto and the Guapiacu River in the state of Rio de Janeiro. They separated recently fed female mosquitoes and studied them under laboratory conditions.

DNA was extracted from the mosquitoes' blood, and a specific gene, serving as a biological barcode unique to each vertebrate species, was sequenced. By comparing these barcodes with reference databases, the team was able to identify which animals the mosquitoes had bitten.

The traps collected 1,714 mosquitoes of different species, among which 145 females were found to have blood. Researchers were able to identify blood sources in 24 individuals, including 18 humans, one amphibian, six birds, one dog, and one mouse.

Some mosquitoes fed on the blood of more than one host. For instance, one mosquito of the species Cq. venezuelensis took blood from both an amphibian and a human. Others, such as Cq. fasciolata, also exhibited mixed feeding, including combinations of rodents and birds, as well as birds and humans.

Researchers believe that this trend can be explained by several factors. “Mosquito behavior is quite complex,” noted Alencar. “While some species may have innate preferences, the availability and proximity of hosts play a key role.”

With ongoing deforestation and the expansion of human settlements, many species of plants and animals are disappearing. In response to such changes, mosquitoes are moving closer to humans, adapting their feeding habits.

Mosquito bites can pose a serious health threat. In the regions where the study was conducted, mosquitoes carry viruses such as yellow fever, dengue, Zika, Mayaro, Sabia, and chikungunya. These infections can cause long-term complications. Researchers emphasized the importance of understanding mosquito dietary preferences to study the spread of diseases in ecosystems and among populations.

The work also revealed shortcomings in current data: less than seven percent of the captured mosquitoes showed traces of blood during feeding, and sources could only be identified in 38 percent of cases. This indicates the need for larger and more detailed studies, including improved methods for detecting mixed blood sources.

Nevertheless, the results obtained may already have practical value. They could help in developing measures to combat mosquitoes and improve early warning systems for disease outbreaks.

“Knowing that mosquitoes in certain regions prefer specific types of blood signals to people the risk of infection transmission,” added Machado.

“This allows for targeted monitoring and preventive measures,” concluded Alencar. “In the long term, this could lead to the development of control strategies that take into account the ecosystem balance.”

Read also:

The Ministry of Natural Resources proposes to approve the rules for the transboundary transport of hazardous waste

The Ministry of Natural Resources, Ecology, and Technical Supervision has presented for public...

Who is turning the Naryn River into a sewage ditch?

It is unlikely that any of us has seriously thought about where the water goes when it is poured...

Unexpected Ways to Protect Against Mosquitoes

18 Unexpected Life Hacks Against Mosquitoes Most likely, mosquitoes were invented for the sake of...

Creeping Transformation of Issyk-Kul

The Issyk-Kul Institute of Resort Tourism has completed the first stage of the General Scheme for...

The Ministry of Natural Resources proposes to shorten the terms of environmental expertise.

The Ministry of Natural Resources, Ecology, and Technical Supervision has developed a draft...

A conference on wildlife protection is taking place in Bishkek.

On October 22, an international conference dedicated to wildlife conservation and the development...

A new state program for biodiversity conservation until 2040 was presented in Bishkek

A national seminar was held in the capital of Kyrgyzstan, where the state program for biodiversity...

Ecologists: It's Time to Save the Floodplain Forests of Kyrgyzstan

Recently, an annual tree planting event organized by the Public Association of Gardeners...

"Bishkek Residents Concerned About the Environmental Situation in the Capital"

On April 3, a mass protest called "We are suffocating" took place in the capital of...

Sadyr Japarov: The Snow Leopard is the soul of our snow-covered mountains, the guardian of inaccessible peaks, a living symbol of freedom, resilience, and devotion to the homeland.

The President of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov, delivered a speech dedicated to the International Snow...

The delegation of Kyrgyzstan participates in the 30th UN Climate Change Conference COP30 in Brazil

The delegation of Kyrgyzstan, headed by Deputy Prime Minister Edil Baysalov and the...

The Ministry of Natural Resources Proposes New Rules for Plant Collection in Kyrgyzstan

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received...

UNDP: The Biodiversity of Kyrgyzstan Requires Systematic Protection and Strategic Measures

Alexandra Solovyova, the UNDP Resident Representative in Kyrgyzstan, emphasized the importance of...

Kyrgyzstan presented its experience in the conservation of rare species at the CITES conference

At the 20th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered...

What is happening to the glaciers of Kyrgyzstan

The melting of glaciers "has been going on for thousands of years. It is a natural process....

In the village of Jalal-Abad region, a local resident illegally cut down 22 poplar trees

On November 10, the Jalal-Abad Regional Office of the Ecological and Technical Supervision Service...

In the Ala-Archa Nature Park, eco-feeders for birds have been installed

Ecological feeders for birds have been installed in the Ala-Archa Nature Park, made possible...

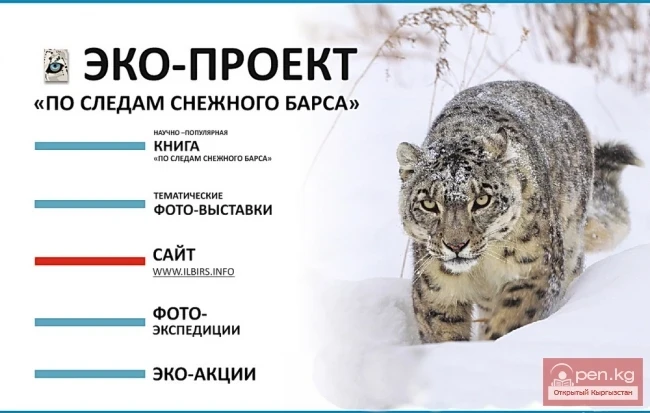

The photo exhibition "In the Footsteps of the Snow Leopard" opened at the IZO Museum in Bishkek.

The long-awaited exhibition "In the Footsteps of the Snow Leopard" has opened at the...

The ban on the export of catalytic converters to the Kyrgyz Republic may be extended for another six months.

The Ministry of Economy and Commerce of the Kyrgyz Republic has initiated a public discussion on a...

Fighting Smog. A Smoke Filter Operating Without Electricity is Being Installed in Bishkek

— This filter consists of two components: the first blocks soot, and the second absorbs smoke and...

"Guy Who Defended His Brother Turned Out to Be a Criminal": The Stories of Police Captain Kanat Madylov

The senior police officer of the public safety department of the Panfilov District Internal Affairs...

President Japarov: We have a unique nature, and we must treat it with respect

President Sadyr Japarov emphasized the need for a respectful attitude towards our unique nature at...

Gold, the Shallowing of Issyk-Kul, Climate, the Carbon Market, and Smog: A Major Interview with the Head of the Ministry of Natural Resources, Meder Mashiyev, on the Results of 2025

The Minister of Natural Resources, Ecology and Technical Supervision, Meder Mashiev, summarizes the...

Kyrgyzstan Promotes Mountain Agenda at COP-30 in Brazil

Kyrgyzstan, represented by the special representative of the president for the mountain agenda,...

Kyrgyzstan Shared Its Experience in Restoring the Population of the Gazelle on the International Stage

At the 20th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered...

The upper area of the Botanical Garden is also planned to be cleared, where laboratories and experimental plots will be located.

As part of the project to improve the Botanical Garden, it is planned to tidy up the area...

El Niño will become more powerful and dangerous by 2050, study finds

A group of international scientists reports on potential serious changes to the climate phenomenon...

Cars, Catalysts, and Technical Inspection: The Minister of Natural Resources on Efforts to Combat Air Pollution. Interview

On October 21, a multilateral dialogue on combating transport-related air pollution in the country...

A Carbon-Neutral Forest Area is Being Created in the Botanical Garden

In Kyrgyzstan, at the base of the E. Gareev Botanical Garden, a project has been launched to create...

Ecology — A Category of National Security

A meeting of the permanent commission of the Inter-Parliamentary Assembly (IPA) of the CIS on...

The shallowing of Lake Issyk-Kul is present, but it is more of a cyclical nature, - Minister Meder Mashiev

According to the minister, the shallowing of Lake Issyk-Kul is observed; however, its nature is...

Eco-feeders for Birds Installed in "Ala-Archa"

On November 22, 40 wooden bird feeders were installed in the Ala-Archa Natural Park. These feeders,...

The deputy requests to preserve the Botanical Garden in Bishkek instead of constructing football fields on its territory.

Deputy Dastan Bekeshev noted on January 14 at a meeting of the Jogorku Kenesh that the Botanical...

In the country, the amount of precipitation has decreased. What will December be like?

In Kyrgyzstan, a prolonged drought is observed, which negatively affects water resources and...

The Ministry of Internal Affairs proposes to allow law enforcement officers to handle cases related to crimes in the field of environmental safety.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic has initiated a draft law proposing to...

In Osh Region, 3 men illegally kept 7 grey-headed goldfinches in a cage. They were fined 30,000 soms.

On January 1, inspectors from the Osh Regional Department of the Ecological and Technical...

Camera traps recorded a snow leopard, a bear, and other animals in the Naryn State Nature Reserve

In the Naryn State Nature Reserve, snow leopards, bears, and other animals have been recorded. To...

On the shore of Issyk-Kul, a large number of fry were spotted

Recently, a video became available in the Kyrgyz segment of social media, showing an abundance of...

Responsibility for Driving Without Catalytic Converters Proposed to be Introduced in Kyrgyzstan

Deputy of the Jogorku Kenesh Marlen Mamataliyev has proposed an initiative to develop a draft law...

The Ministry of Natural Resources proposes to allow the circulation of only biodegradable bags.

The Ministry of Natural Resources, Ecology, and Technical Supervision has presented for public...

In the Issyk-Kul Region, winter feeding of white swans was conducted

In the Issyk-Kul region, specialists from the regional office of the Ecological Supervision Service...

Life in the Regions: A Group of Foreigners Bought Felt Beads from Kerimzhan Kadyrkulova

58-year-old Kerimzhan Kadyrkulova, living in the village of Min-Bulak, is engaged in the production...

The international forum "Business, Ecology, and Sports - Ak-Irbis 2025" is taking place in Bishkek. Photo

On October 23, the forum "Business, Ecology, and Sports — Ak-Irbis 2025" was launched in...