Photo from the internet

According to the researchers, Tashkent, Bishkek, Almaty, Astana, and Dushanbe have not yet reached a critical point, but their situation is becoming increasingly alarming. The main factors contributing to this are the rapid melting of glaciers, outdated infrastructure, and excessive water consumption, particularly in agriculture. Notably, up to 90% of water resources are used for irrigation, and a significant portion is lost in open channels before reaching agricultural lands; in some areas, up to 40% of water simply evaporates on its way to the fields.

The authors of the study emphasize that the illusion of sufficient water resources no longer corresponds to reality: groundwater levels are declining, soils are becoming more saline, and ecosystems are degrading. These negative changes are already being observed in the Aral Sea basin and may herald serious problems for cities in the future.

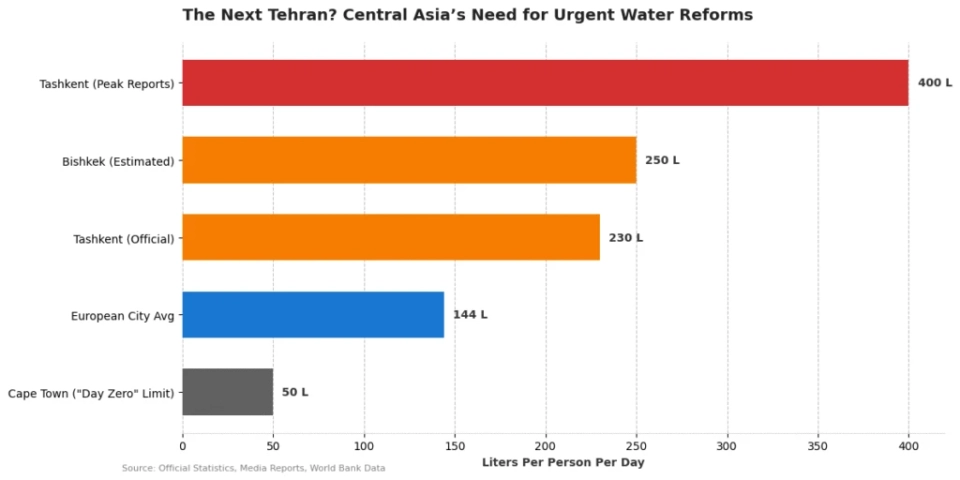

Particular attention is paid to the state of water supply systems in the capitals of the region. In Tashkent and Bishkek, water supply networks largely date back to the Soviet era and often require emergency repairs. Uzbekistan demonstrates one of the highest levels of water consumption in the world — up to 400 liters per person per day, which is almost twice the figures of European cities. This creates vulnerability for megacities — even minor disruptions in supply can lead to mass water outages.

Photo from the study

Kurbanov and Guseynova also point to management shortcomings exacerbating the crisis. Water tariffs do not cover the costs of maintaining infrastructure, and water agencies remain weaker than agricultural ones, which continue to increase consumption. An additional source of tension is the situation in Afghanistan: the under-construction Kosh-Tepa canal, which could divert up to a third of the Amu Darya's flow, is already affecting water supply in southern Uzbekistan, which could lead to a redistribution of water resources in Central Asia and pose a threat to Kazakhstan.

Bad weather also exacerbates the situation. According to meteorological services, precipitation in some areas has been 40-70% below normal. In Tajikistan, electricity restrictions have already been introduced — up to three hours a day in rural areas. Without rain, air quality deteriorates, leading to increased pollution levels.

The authors call for immediate reforms to avoid rising migration, escalating social conflicts, and increasing competition for water resources among states. To prevent a "Tehran moment" in Central Asia, it is necessary to modernize irrigation systems, minimize losses in water supply networks, develop alternative energy sources, tighten urban development regulations, and establish a sustainable tariff policy.

A key aspect becomes the need to establish dialogue with Afghanistan regarding the management of the Amu Darya river flow. Otherwise, as Kurbanov and Guseynova note, the water crisis will gradually escalate until it reaches critical proportions.