The Economy of the Kyrgyz in the 18th to Early 20th Century

The development of internal trade in Kyrgyzstan, especially from the beginning of the 20th century, contributed to a lively exchange of goods between the nomadic and settled populations. The relatively small number of trade-industrial, even agricultural populations in the northern part of Kyrgyzstan led to herders selling their products in cotton-growing and industrial areas of the south. Cattle and livestock products were supplied there through fairs or by organizing drives across mountain passes. Thus, in the early 20th century, industrial animal husbandry began to emerge in Kyrgyzstan. In Northern Kyrgyzstan, agricultural products also entered the trade turnover. Most of them were sold locally, but a certain portion went beyond the region. A significant share of agricultural production was accounted for by the Kyrgyz.

After the 1880s, the area under cultivation for technical crops (primarily cotton) expanded in the Fergana Valley, and an industrial population emerged. This led to an increased demand for food products from the settled population, which accelerated the process of the Kyrgyz settling down and increased the area under cultivation. Thus, trade (especially in the early 20th century) gave a strong impetus to the development of the internal market in Kyrgyzstan. However, it should be noted that due to the "division" of Kyrgyzstan among several regions, it found itself within two regional markets—the Fergana and Semirechye markets, the centers of which were located outside the territory of Kyrgyzstan. This circumstance complicated the formation of the internal market.

During the colonial period, small commodity production in Kyrgyzstan developed slowly.

Gradually, with the development of capitalism, some types of local crafts were increasingly reduced, and some, such as the production of household metal and wooden items, lost their former significance. Now the needs of the Kyrgyz for these goods could be met by factory products brought from Russia. Nevertheless, many types of home crafts continued to exist, closely tied to the nomadic and semi-nomadic lifestyle of the local population. The products made here were competitive with industrial goods from Russia. Therefore, with the annexation of the region to Russia, there was even some development of such crafts. This is evidenced by data on the number of artisans in Kyrgyzstan.

From the 1880s to the 90s, small enterprises processing primarily agricultural raw materials emerged in the cities and large villages of Kyrgyzstan. Over 30 years (1883-1913), their number increased from 165 to 569. These were enterprises in the processing and extractive industries, large mills, etc. In most cases, they were based on the use of manual labor. Seasonality of work was characteristic of many cottage industry enterprises.

In the early 20th century, relatively large capitalist enterprises appeared in both the processing and extractive industries. This was associated with the penetration of Russian and partly foreign capital. By their technical and economic indicators, they corresponded to capitalist enterprises of factory-type in central Russia. These included cotton ginning factories in the villages of Aravan and Naiman, breweries, leather factories, and several wool washing facilities in Pishpek, Przhevalsk, and Osh, as well as large coal mines and oil fields on the territory of Kyrgyzstan.

The Russian government aimed for the natural resources of the region to be primarily utilized by Russian capitalists. Nevertheless, some foreign entrepreneurs and shareholders still penetrated Turkestan. This was usually accomplished through the participation of foreign capital in joint-stock companies established in Russia or in companies where the majority of members were Russian subjects. Thus, in the early 20th century, firms such as the "Administration of the Andreyev Trade and Industrial Partnership," "Ludwig Rabenek Manufacturing Partnership," the Fergana Oil and Mining Joint-Stock Company "Chimiyon," the Joint-Stock Company "Kyzyl-Kiya," and several others began to operate actively in the region.

In 1913, there were 32 enterprises of various sectors in Kyrgyzstan: seven coal mines (employing about 1,000 workers), two oil fields, two cotton ginning factories, seven wool washing facilities, two oil mills, two breweries, five roller mills, and several other enterprises. Among them, the largest were the wool washing factories in Tokmak (100 workers) and in the Pishpek district (235 workers), the brewery in Osh (84 workers), and two coal mines: in Kyzyl-Kiya (598 workers) and in Suluktu (207 workers).

If, in general, the processing industry was dominant in terms of size and technical-economic indicators in the Turkestan region, then in Kyrgyzstan, it was the mining industry. The capital of most joint-stock companies operating in Kyrgyzstan (there were more than 10, and their turnover was about 10 million rubles) was invested in mining. It accounted for 50% of the production and 59% of the workforce.

For some time, the Kyrgyz paid taxes to the tsarist authorities similar to those paid to the Kokand Khanate. Later, new taxation mechanisms were developed according to local conditions. According to the adopted norms, nomadic herders paid a tax of 2 rubles and 75 kopecks for each yurt. Since the land was considered state property, a payment of 3 kopecks was required for each sheep grazed, 30 kopecks for a horse, and 50 kopecks for a camel. From 1882, the tax rate increased and reached 15 rubles during the First World War.

The settled population was subject to two types of taxes. A kharaj was levied on grain areas, and a tanap on garden and vegetable areas. Tanap is a measure of area, and kharaj amounted to one-tenth of the harvest and was paid in kind. In 1886, the procedure for collecting tanap was slightly modified. This type of tax was renamed obrok and had to be paid on all arable land, regardless of whether it was cultivated or not. In addition to the taxes established by the tsarist government, local bai-manaps, relying on traditional patriarchal-feudal law, imposed additional levies and payments on ordinary people: for grazing livestock—chep ooz, for honoring manaps—chyghym, in kind from livestock and grain—zhurtchuluk, for sustenance—soiush, for driving livestock through their territory—tuyak pul, for weddings and funerals—koshumcha, and others. Religious officials had their own tax system. Corruption among local officials became a common occurrence.

Read also:

Tourist Area Management Program

The project "USAID Business Development Initiative" (BGI), within the tourism...

Dobaev Kyrgyzbay Dushenbekovich

Dobaev Kyrgyzbay Dushenbekovich (1954), Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences (2000) Kyrgyz. Born in the...

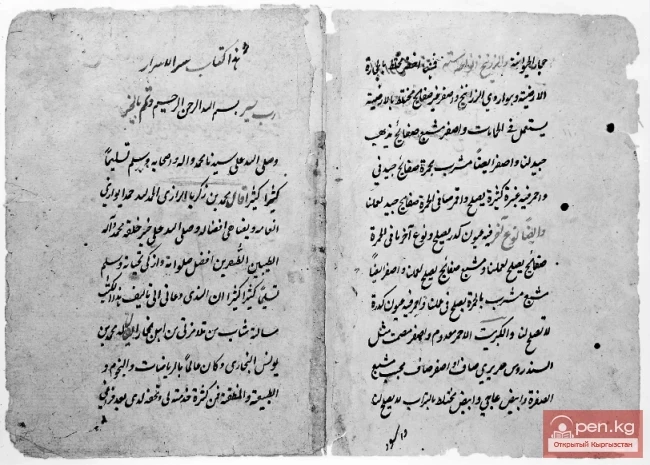

Kyrgyz Waqf of the 19th Century

Kyrgyz Vakf The so-called Kyrgyz vakf of the 19th century is not an exceptional phenomenon,...

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich (1936), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995),...

Types of Higher Plants Listed in the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985)

Species of higher plants removed from the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985) Species of...

Types of Insects Listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS Not Included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS, not included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan 1....

Evasion of Tax Payments by Waqf Founders

Waqf Documents Undoubtedly, the waqf madrasa of Alymbek is one of the largest agricultural estates...

Zhorobekov Zholbors

Zhorobekov Zholbors (1948), Doctor of Political Sciences (1997) Kyrgyz. Born in the village of...

Madrasah "Alymbek-chek" in the city of Osh, Fergana Region

Waqf Rights of the Madrasah "Alymbek-chek" According to archival documents, the madrasah...

A concert by the State Academic Russian Folk Ensemble "Russia" named after L. Zykina will take place in Bishkek.

On November 18, a concert of the State Academic Russian Folk Ensemble 'Russia' named...

Toktusun Ashirbaev (1948), Doctor of Philological Sciences

Ashirbaev Toktosun (1948), Doctor of Philological Sciences (2001). Kyrgyz. Born in the village of...

The title translates to "Poet Soviet Urmambetov."

Poet S. Urmambetov was born on March 12, 1934, in the village of Toru-Aigyr, Issyk-Kul District,...

Aktanov Toychu Kuluntai Uulu (1910-1942)

Aktanov Toichu Kuluntay Uulu (1910-1942) - a representative of the first generation of Kyrgyz...

Prose Writer, Journalist Djapar Saatov

Prose writer, journalist Dzh. Saatov was born on February 15, 1930, in the village of Alchaluu,...

Poet, Critic, Literary Scholar Omor Sooronov

Poet, critic, literary scholar O. Sooronov was born in the village of Gologon in the Bazar-Kurgan...

95th Anniversary of Turdakun Usubaliev. Opening of the Book Exhibition at the National Library

Since October 14, 2014, a book exhibition titled “A State Figure Who Became a True Legend” has...

Poet Abdravit Berdibaev

Poet A. Berdibaev was born on 9. 1916—24. 06. 1980 in the village of Maltabar, Moscow District,...

Prose Writer, Poet Junay Mavlyanov

Prose writer and poet J. Mavlyanov was born in the village of Renzhit (now the village of...

The Poet Gulsaira Momunova

Poet G. Momunova was born in the village of Ken-Aral in the Leninpol district of the Talas region...

Poet, Prose Writer Anatoliy Omurkanov

Poet and prose writer A. Omurkanov was born on June 2, 1945, in the village of Chesh-Dyube, Manas...

Waqf - One of the Original Forms of Land Ownership

When examining the documents regarding the waqf of the Alymbek madrasa, it is hard not to agree...

Prose Writer Kachkynbay (KYRGYZBAI) Osmonaliev

Prose writer K. Osmonaliev was born on March 5, 1929, in the village of Chayek, Jumgal district,...

Poet, Prose Writer, Translator Tolegen Kozubekov

Poet, prose writer, translator T. Kozubekov was born on February 10, 1937, in the village of...

The Poet Tenti Adysheva

Poet T. Adysheva was born in 1920 and passed away on April 19, 1984, in the village of...

The Poet Subayilda Abdykadyrov

Poet S. Abdykadyrova was born in the village of Sary-Bulak in the Kalinin district of the Kirghiz...

International Conference "Modern Media: Challenges and Risks" in the Capital of Kyrgyzstan

On November 25, at 9:30 AM, the international conference "Modern Media: Challenges and...

Poet, Prose Writer Medetbek Seitaliev

Poet and prose writer M. Seitaliev was born in the village of Uch-Emchek in the Talas district of...

The Poet Suyunbai Eraliyev

Poet S. Eraliyev was born on October 15, 1921, in the village of Uch-Emchek (now the Talas...

Poet, storyteller-manaschi Urkash Mambetaliev

Poet, storyteller-manaschi U. Mambetaliev was born on March 8, 1934, in the village of Taldy-Suu,...

Concert of the Russian Folk Ensemble "Russia" named after L. Zykina (Moscow)

On November 18, 2014, at 6:30 PM, a concert of the State Academic Russian Folk Ensemble...

Poet Abdilda Belekov

Poet A. Belekov was born on February 1, 1928, in the village of Korumdu, Issyk-Kul District,...

Salamatov Zholdon

Salamatov Zholdon (1932), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995), Professor (1993)...

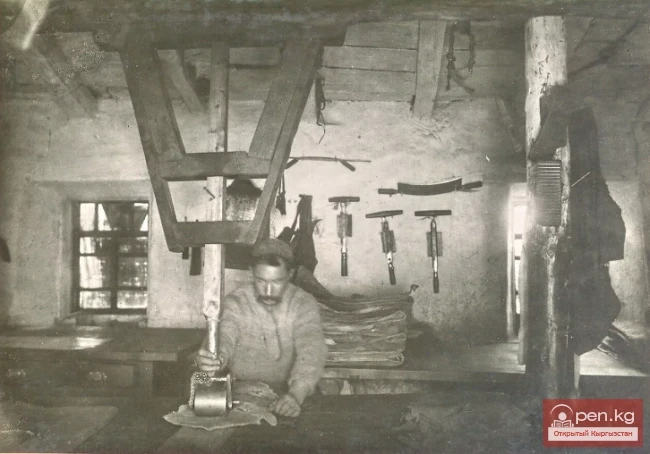

Records of the Tannery Factory of the City of Pishpek. Document No. 10 (November 1886)

REPORT ON THE LEATHER FACTORY OF THE CITY OF PISHPEK, SENT BY THE HEAD OF THE TOKMAK DISTRICT TO...

Poet Mariyam Bularkieva

Poet M. Bularkieva was born in the village of Kozuchak in the Talas district of the Talas region...

Preservation of the Waqf of Alimbek after the Fall of the Kokand Khanate

Attempts to Circumvent Legislation on the Expansion of Waqf The conversion of real estate into...

Prose Writer, Critic Dairbek Kazakbaev

Prose writer and critic D. Kazakbaev was born on June 20, 1940, in the village of Dzhan-Talap,...

The Poet Akbar Toktakunov

Poet A. Toktakunov was born in the village of Chym-Korgon in the Kemin district of the Kyrgyz SSR...

Waqf Medrese of Alymbek

Mutawalli of the Waqf Thus, from the mentioned documents, it is clear that Alimbek, having...

Critic, Literary Scholar Abdyldazhan Akmataliev

Critic and literary scholar A. Akmataliev was born on January 15, 1956, in the city of Naryn,...

Poet Dzholdoshbay Abdykalikov

Poet J. Abdykalikov was born in the village of Tashtak in the Issyk-Kul district of the Issyk-Kul...

Poet Mukambetkalyy Tursunaliev (M. Buranaev)

Poet M. Tursunaliev was born on January 11, 1926, in the village of Alchaluu, Chui region of the...

Poet Mederbek Akimkodzhoev

Poet M. Akimkodzhoev was born in the village of Bazar-Turuk in the Jumgal district of Naryn region...

The Poet Jumakan Tynymseitov

The poet J. Tynymseitova was born on 11. 1929—29. 07. 1975 in the village of On-Archa in the...

Poet, Prose Writer Abdrasul Kylychev

Poet and prose writer A. Kilychev was born in the village of Orto-Sai near the city of Naryn in...

Chorotegin (Choroev) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich

Chorotegin (Choroев) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich (1959), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1998),...

Improvisational Poet Toktonaly Shabdanbaev

The improvisational poet T. Shabdanbaev was born on August 15, 1896 — February 18, 1978, in the...

Fauna of the Chui Valley

The fauna of the Chui Valley is part of the Western Tienir-Tous zoogeographic region. According to...