Climate Conditions and New Challenges

Unfortunately, the new location has not met the sellers' expectations.“It’s too hot here, it’s raining, and there’s no roof. The toilet is in poor condition,” the vendors share their disappointment. Previously, they were sheltered by the shade of trees and awnings, but now the bright sun blinds customers, making it difficult for them to see the goods.

“People walk by and hardly see anything. It’s very sad,” says one of the sellers. In rainy weather, many of them prefer not to come out to avoid damaging their products.

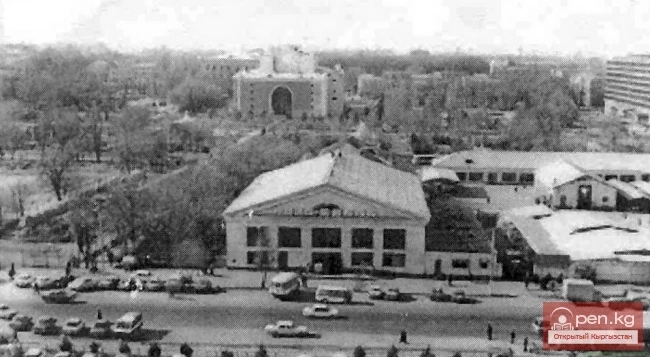

The key problem with the new location is the sharp decrease in customer traffic. The previous site was in the heart of city life.

“There was good foot traffic there. Selling is a spontaneous activity. A person walks by, sees something interesting, and buys it. Now, to attract attention, people need to come here intentionally,” explains Veronika, who has been in trade for over twenty years.

The Culture of Flea Markets and Their Role in City Life

Flea markets are common worldwide, but in Bishkek, they hold a special place in urban culture, especially after the 90s when the sale of old items began for income. It is a space for finding inexpensive vintage items, books, and rarities, including Soviet bonds and various props. Despite their popularity, public perception of these markets remains ambiguous: for some, it’s nostalgia, while for others, it’s just chaos of old things.For many sellers, like Veronika, this is not just a job but a way of life.

“On weekdays, I work, and I only come here on weekends. It’s a kind of club for socializing. You need to breathe fresh air and communicate, and also earn a little,” she shares.

After the move, sales have noticeably decreased. For them, a successful day is considered to be earning 1,500 soms on a weekend and 700-800 soms on a weekday, while at the previous location, revenue could reach three to four thousand soms.

Changing Audience: Who Now Comes to the Market

Sellers note that the composition of visitors has changed.“There are almost no young people here. They used to come, drink coffee, and buy something. Now this is not observed,” states one of the vendors.

Now, the main customers have become elderly people and collectors.

One of the sellers adds that her sales have significantly dropped, and it is hard for her to pay the rent, which ranges from 100 to 200 soms.

Prices for Soviet badges start from 10 soms for an ordinary specimen.

“Prices depend on the year of production and condition. There are many nuances,” explains an enthusiastic trader. Experts come here to exchange opinions and discuss artifacts, but such customers are very few.

Hope for Improvement and the Need for Information

Sellers are convinced that the solution to the problem lies in informing the public.“We need to hang a sign saying 'flea market' at the entrance and indicate that we are open on Saturdays and Sundays from 7 AM to 2 PM. That way, people will know we are here,” they believe.

For now, the new location remains in the shadows even for regular customers. The flea market, once a symbol of spontaneous finds, has now become a hard-to-reach place. Its future depends on whether city residents can rediscover this unique space, full of history and communication, or if it will remain just a quiet “club for socializing” on the outskirts of urban life.