The instruction from President A. Atambayev to the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic to reform the science system and create conditions for the revival of scientific activity in the country has caused noticeable resonance in society. Such attention from the head of state to the problems of science, in my opinion, is a very significant and timely phenomenon. Of course, during the period of universal globalization, science also needs optimization. I fully support our president's desire to see Kyrgyz science closely integrated with global science, bringing real benefits to the national economy of the country. Today, both the demands on science and the public's attitude towards it must fundamentally change. There is no alternative to this, for tomorrow may be too late.

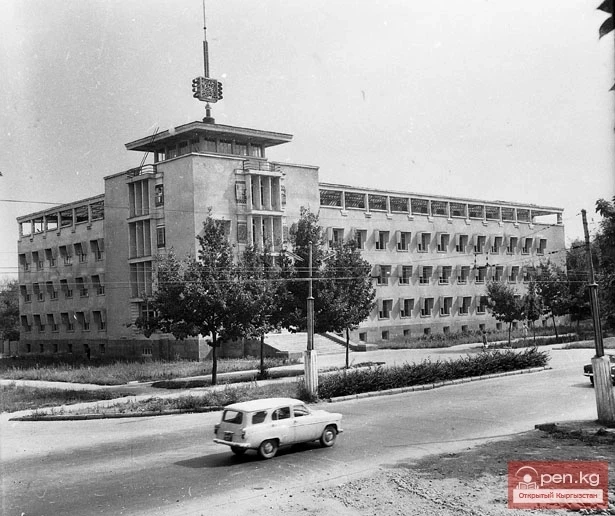

The current state of science and its future cause quite justified concern. To put it bluntly, the state's cool, if not completely indifferent, attitude towards science began at the time the country gained sovereignty. Over the past nearly quarter-century, twenty-five governments have changed in Kyrgyzstan, none of which have cared about the financial, social, and material-technical needs of scientists. The decent scientific and technical base left over from the Soviet era has long since become outdated, and a large part of the young, promising scientific forces has irretrievably left for the market. The remaining group of people devoted to science continues to work quite successfully, but everything has not only a beginning but also an end, determined by age and physical resources. In my opinion, the folk wisdom of regret fits science best: “If youth knew, if old age could!” Next to the seasoned, all-capable, but unfortunately not all-able scientists, there should grow a young generation that is capable of much but has not yet learned much, which will become a scientific school in due time...

Some hope for the development of science comes from the fact that after the revolution of 2010, relative stability has been established in our lives, and the number of young people in science has begun to grow, albeit slowly.

I cannot overlook the trend that has become fashionable in recent years, namely, the desire of high-ranking officials and deputies to obtain scientific degrees of candidates and doctors of sciences in such social disciplines as economics, law, philology, philosophy, and political science. It has been said: “Demand creates supply.” A whole layer of scientific workers has emerged, who “bake” candidate and doctoral dissertations for a price much higher than their salaries. Newly minted doctors of sciences, with their characteristic audacity, strive to buy high titles of academicians, corresponding members, and become laureates of state awards. They not only quantitatively increase the number of scientists but, more frighteningly, show others that everything can be bought and sold. I believe that these processes need to be met with an insurmountable legislative barrier.

Currently, three types of scientific workers can be identified in science: 1) true Scientists, working for the benefit of society and for their own benefit; 2) scientists working for their own benefit; 3) pseudo-scientists. It is the latter who shamelessly buy not only dissertations but also those who are practically ready to defend their theses, graduate students, and even doctoral candidates. In true science, this is the lowest point of a specialist's decline.

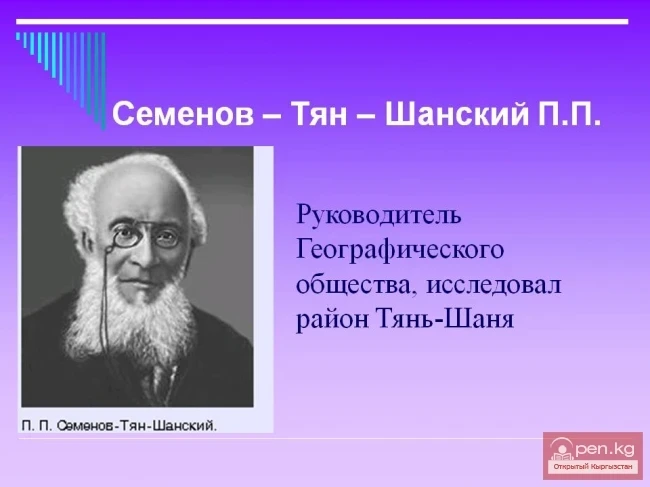

The word “reform” has frightened many of us for many years. There are reasons for this; we have many cases in our memory when, under the guise of this word, practically perfectly functioning enterprises were ruined. Why go far, the infamous “perestroika,” and this word, albeit distantly, is a synonym for “reform,” led to the collapse of the vast state of the USSR, which occupied one-sixth of the Earth's land. However, to avoid stagnation, any organization should be subjected to changes from time to time. Yes, science needs optimization; this is especially relevant now. But how to achieve this? In this matter, haste is destructive; it is no coincidence that wise ancestors warned us, “Measure seven times, cut once.” It has become fashionable to cite Kazakhstan and Russia as examples for various problems. But in the activities of their academies of sciences, numerous problems have emerged after the reforms, which still resonate today. In Kazakhstan, for example, everything remains the same, except that now the projects of the institutes of the Academy of Sciences are financed by the Ministry of Education, and newly elected academicians and corresponding members do not receive scholarships. Currently, there is work at the government level to restore the former Academy of Sciences. It should be noted that President N. Nazarbayev pays a lot of attention to the development of science. Thus, two years ago, at his initiative, the Turkic Academy was formed, the creation of which was warmly supported by our president A. Sh. Atambayev. Moreover, its establishment was approved by the “Bishkek Declaration,” adopted at the summit of the presidents of Turkic-speaking states.

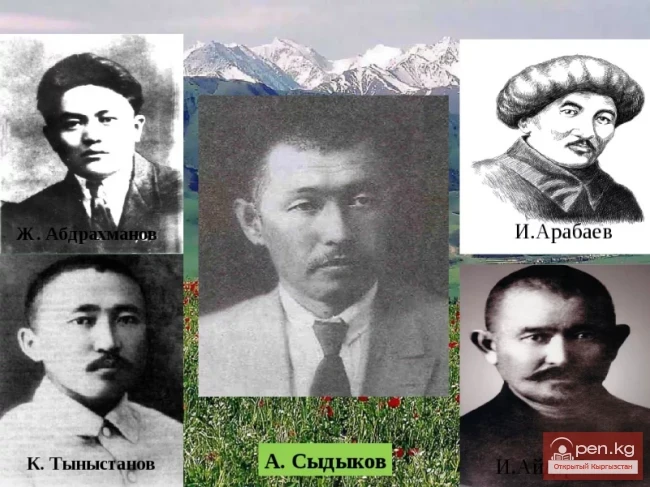

National science in the humanities is needed by every state at the forefront, for it is its face, one of the main attributes. Without language, literature, history, philosophy, and political science, there is no state; they give us the right and opportunity to call our country the Kyrgyz Republic. It is no coincidence that language, literature, history, and philosophy have become the scientific foundation on which our Academy was established. In no other part of the world will our language, literature, history, and culture be studied, and no country will ever provide us with investments for them. National sciences are the foundation of state ideology, the spiritual mirror of society.

Our president never tires of repeating the need to develop the state language, study the epic “Manas,” and the history of the Kyrgyz Khaganate. The founder of the Turkish state, Atatürk, highly valued the humanities, which is why in the 1930s, he established in his country the “Academy of Language, History, Literature, and Culture.” The recommendation of the Public Expert Council on Education under the president (which includes one doctor and one candidate of sciences!?) to grant the humanities a public status is an attempt to cut off a half-dried branch on which poets and writers, artists, composers, cultural, educational, and scientific workers have been cramped for over twenty years, leading a semi-starved existence. The recommendation, I want to believe, was likely made out of misunderstanding by the authors, who forgot the wise warning of the great fabulist: “It is a disaster when a shoemaker begins to bake pies, and a pie maker starts to make shoes...” Judging by the fact that the representatives of this expert council did not dare to accept the invitation to attend the general meeting of the Presidium of the National Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz Republic to discuss their “Recommendations...,” they simply voted “odamryams” for the hastily baked text by a poor pastry chef.

The humanities will always need state care; such is their specificity. If there are state orders, there will be basic funding; along with this, a “Science Fund” will be created under the Government, from which project funding will be carried out on a competitive basis, and the results of our scientific research will be incomparably higher.

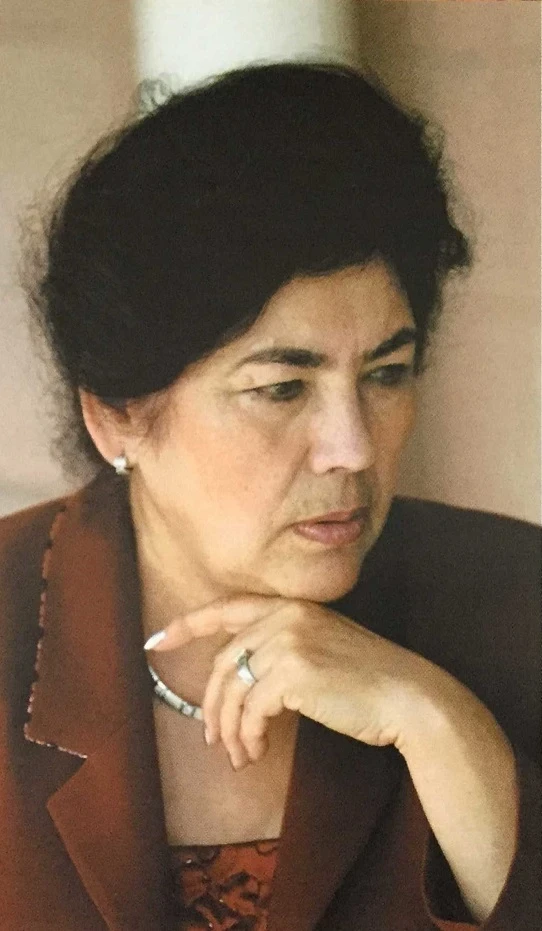

A.A. Akmataliev