The first patient to undergo this treatment is 13-year-old Alyssa Tapley, who was featured by the BBC in 2022. To date, she shows no signs of new cancer cells. Alyssa, who once believed she was destined to die, is now healthy and dreams of becoming a doctor to help other cancer patients.

A research team from two London hospitals — Great Ormond Street Hospital and University College London Hospital — published the results of this experimental treatment in the New England Journal of Medicine, detailing the treatment of Alyssa and ten other patients, including eight children and two adults.

According to the report, nine out of eleven patients achieved deep remission, allowing for a bone marrow transplant.

Among these patients, seven showed no new signs of the disease for three months to three years after therapy.

However, the report's authors emphasize that one significant risk of this approach is infections that occur during the period when the patient's immune system is temporarily disabled.

In two cases out of eleven, cancer cells and modified donor T-cells lost the CD7 marker, allowing them to evade treatment.

"Given the aggressiveness of this form of leukemia, the results are astonishing, and I am glad we were able to give hope to patients who would otherwise have lost it," noted Dr. Robert Kieza from the bone marrow transplant department at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

During the treatment, the genes of the T-cells were modified. These cells normally protect the body by destroying infections, but in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, they begin to act against it.

The experimental treatment was the only option for patients who did not respond to chemotherapy and bone marrow transplants. Without it, the only remaining path was palliative care before death.

"I really thought I would die and wouldn’t be able to fulfill my dreams like all children," recalls Alyssa Tapley from Leicester. She is now 16 years old, and the new method was applied to her three years ago.

Now, three years after treatment, Alyssa is enjoying life and making plans for the future.

Three years ago, doctors completely shut down her immune system and rebuilt it. She spent four months in the hospital, and even her family was not allowed to visit to avoid infection.

Today, Alyssa shows no signs of cancer, and she only needs to undergo examinations once a year. She is preparing to graduate from school, wants to learn to drive, and is making plans for life.

"I’m thinking about becoming an intern in biomedicine, and then, hopefully, I can research blood cancer," she shares.

Base Editing

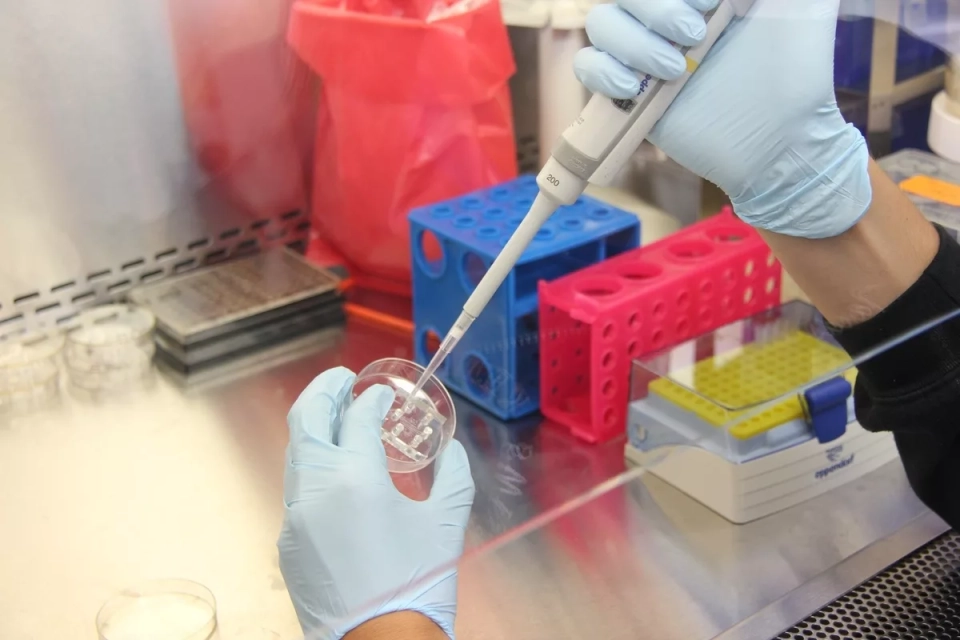

The gene therapy method used is called base editing.

Nitrogenous bases are organic compounds that are components of nucleic acids. The four types of bases — adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T) — form the genetic code.

Like letters of the alphabet, billions of bases in our DNA provide instructions for the functioning of the human body.

Base editing allows scientists to select specific fragments of the genetic code and alter the molecular structure of individual bases, thereby making corrections to genetic instructions.

The team of doctors and scientists who used this method adapted donor T-cells to destroy cancer cells in the patient’s body. This was a complex task, as it required reprogramming healthy donor T-cells so that they would not attack the patient’s own cells.

The editing process consisted of several stages:

- In the first stage, the ability of the patient’s T-cells to target their own cells was disabled.

- The second stage involved removing the CD7 antigen, which is present in all T-cells.

- The third stage prevented cell death from chemotherapy, making them "invisible" to the drug.

- In the final stage, the modified donor T-cells were instructed to destroy all cells containing the CD7 protein, including cancerous ones.

- These modified cells are then reintroduced into the patient’s body. If no cancer cells are detected after four weeks, the patient undergoes a bone marrow transplant to restore the immune system with new healthy lymphocytes.

"A few years ago, this seemed like science fiction," says Professor Waseem Qasim, a member of the team that developed the new method. "We are essentially dismantling the entire immune system. It’s a serious, intensive treatment that is very challenging for patients, but when it works, it yields excellent results."

"These patients had minimal chances of survival before the experimental treatment, and such results inspire hope for the development of similar methods and their availability to more people," commented Dr. Tanya Dexter, a senior clinician at the Anthony Nolan Institute in London, which studies stem cells.