"Crises in Primary Care." Professor Brimkulov on the shortage of family doctors and the need to strengthen primary care.

Attention is focused on forming a healthy lifestyle — giving up alcohol and tobacco, controlling blood pressure and sugar levels, physical activity, proper nutrition, and adequate sleep.

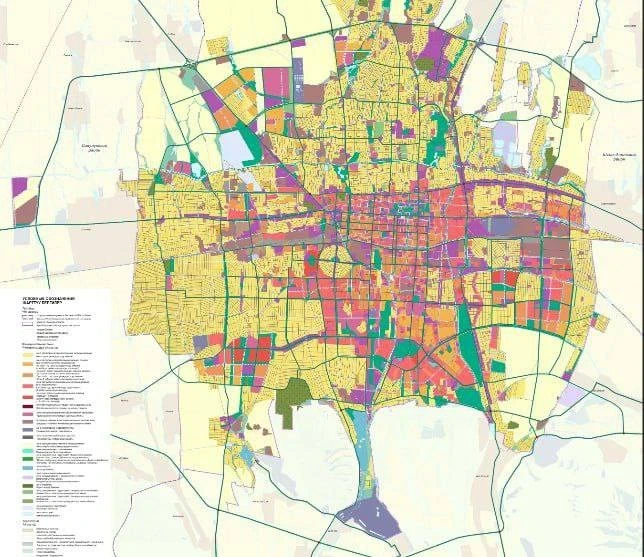

Plans include the creation of a new medical town on the outskirts of the capital, where central tertiary-level institutions will be relocated. In the center of Bishkek, it is proposed to maintain the primary level: family medicine centers, as well as the secondary level: maternity hospitals and city hospitals.

Prevention remains a key area of work for the primary healthcare sector. However, the current situation in this segment remains critical, primarily due to a shortage of personnel. Each year, there is a decline in the number of family doctors and medical staff in polyclinics.

With Professor Nurlan Brimkulov, we discussed the current state of the primary level and the work of family doctors.

- What is the situation with family doctors and the primary level in our country?

- Unfortunately, this is a question that can be discussed endlessly, as the problem remains relevant. We divide the healthcare system into three levels:

The primary level includes primary healthcare: family medicine centers, individual family doctor groups (GSV), FAPs, and General Practice Centers (including their outpatient part, which was previously an independent CSM).

The secondary level mainly consists of the COVP (the part covering the hospitals of former territorial hospitals). After the merger in 2021 of the CSM and territorial hospitals, the boundaries between the primary and secondary levels in Kyrgyzstan have become blurred.

The tertiary level includes republican institutions: the National Hospital, National Centers (NCKT, NCOMID, and others), research institutes, and others.

In countries with a developed primary level, the population receives up to 90-95% of medical services in these institutions. Here, the main preventive work is carried out, including planned immunization. If a country has a population of 7 million, vaccination is carried out for everyone according to the vaccination calendar. In most cases, prevention issues are addressed at the CSM and COVP — this is how it works in countries with an effective primary level.

Of course, some patients require inpatient care, but their number usually constitutes only 7-10% of all visits. High-tech assistance in tertiary-level institutions is needed for no more than 1% of patients.

This is where the problem arises. For the primary level to be strong and capable of serving 100% of the population, there must be personnel, buildings, and conditions. However, in medicine, as in other areas, there are fields where, according to some, more funds should be directed. For example, many dream of becoming astronauts, but the country needs pilots, drivers, and other specialists. In medicine, the situation is similar: the focus is on high technologies, life-saving surgeries, and organ transplants.

Yes, we are already performing kidney and liver transplants, and there is a government program. But if diseases are prevented, the number of such interventions can be significantly reduced. Therefore, resources should be directed to the primary level, to prevention. Traditionally, however, the focus is on building and equipping hospitals.

- There are also serious problems with personnel...

- Currently, we are witnessing a significant crisis: medical personnel are leaving the country. Due to the shortage of personnel, many of our attempts to change something do not yield results. For example, according to statistics, in 2012, there were 54.9 nurses per 10,000 population, and now this figure has dropped to 44.3 (as of 2024). The number of doctors has decreased from 22.5 to 15.8 per 10,000 population.

According to the order, one family doctor should serve 1,700 people, which means that for a population of 7 million, about 4,000 family doctors are needed.

The required number is 4,000, but there are only 3,200 actual positions. Of these, 2,400 are working, but many of them hold multiple positions. The actual number of doctors is about 1,947 (according to last year's data).

Thus, instead of the norm of 1,700 people per doctor, there is an average of 3,400. In cities, the situation is slightly better, but in remote regions, the ratio can reach 10-20 thousand people per doctor.

As a result, according to the international index of accessibility and quality of medical care (HAQ Index), we achieve only about 30%. This means that only a conditional 30% have access to quality care, while the remaining 70% do not. It is clear that people seek help when their condition has already significantly worsened, leading to high dissatisfaction.

According to general data, the population is dissatisfied, and doctors also experience discontent, as they physically cannot cover all patients — there simply aren't enough of them. In total, we have about 13,000 doctors, of which family doctors make up only 10-15%.

In European countries, it is considered that 40-50% of doctors should be family doctors to effectively cover all patients, provide primary care and prevention, and address most issues. If there are not enough family doctors and too many specialists, this leads to fragmentation of medical care. Patients turn to multiple specialists, each of whom prescribes their own tests and treatments.

You have probably encountered patients with entire folders of tests but without a diagnosed condition and without satisfactory treatment. Specialists focus only on their area, and if the problem goes beyond their competence, the patient is referred further. As a result, a person can go to doctors for a long time without receiving comprehensive help.

- Can we say that there is a shortage not only of family doctors but also of specialists?

- There is an overall shortage of personnel in the country. For example, in Kazakhstan, there are 40 doctors per 10,000 population, while this figure is half as low here.

Moreover, Kazakhstan places greater emphasis on the primary level. The salary of a family doctor is about three times higher. They have implemented a new approach — the work of a multidisciplinary team. The family doctor in this team is the leader. The team includes three trained nurses who can independently manage patients. There is also a social worker, a psychologist, and a part-time midwife.

In our case, for example, in Batken, a doctor often works alone — there is no one to consult or share the workload with. In Kazakhstan, however, a whole multidisciplinary team functions. Trained nurses have their own equipped offices, and according to the latest data, in some centers of best practices (CLP), up to 60-70% of patients turn to nurses. They do not need to see a doctor — their needs are met by the nurse. Research shows that educational programs conducted by nurses are often more effective and generate more trust from patients.

For example, a woman comes in with high blood pressure, and she is experiencing anxiety and fatigue. Here, the doctor prescribes medication and gives recommendations, and that’s it. In countries where a team works, the doctor can listen and find out what is happening in the family. A social worker gets involved, a psychologist helps cope with stress, and within a couple of weeks, the blood pressure normalizes. Sometimes medication is no longer needed, as the cause was chronic stress.

Thus, the family doctor is relieved and can focus on truly serious patients. Simple issues, such as prescriptions, explanations, and measuring blood pressure, are handled by nurses. In a number of countries, the number of their independent appointments already exceeds those of doctors, as this is convenient for people. However, this requires well-trained nurses and separate offices where patients can come and talk.

By the way, the Ministry of Health, having studied the experience of Kazakh colleagues, is preparing to implement it in several selected pilot institutions across the country. The directors of these institutions have been trained at the WHO Demonstration Center in Kazakhstan, and serious preparatory work is underway. I hope that the project will be successful and will subsequently be expanded nationwide.

- Currently, the work of nurses is also being reviewed. Now many of them can perform certain actions independently, without a doctor's permission.

- This is logical. Only a doctor can make a complete clinical diagnosis; they prescribe treatment. But a nurse can conduct an independent appointment, make a so-called "nursing diagnosis," educate patients, and much more. For example, if a hypertensive patient comes to her and their blood pressure normalizes, she can explain that the medication should continue, check the indicators, and educate the patient. If the medication is not available at the pharmacy, she can suggest an alternative with the same active ingredient. And if a question arises, she refers the patient to the doctor after measuring all the indicators.

However, for this, she needs a comfortable, well-equipped office, so that both the patient feels trust and she can work fully. However, we often lack space: one pre-doctor's appointment room is made, and two or even three family nurses are placed in it. If three nurses work in one room, and there is not enough equipment for everyone, it becomes clear that such an appointment loses its meaning. In a cramped space, it is uncomfortable for men and women to discuss personal issues, and there is a lack of conditions and equipment. Thus, formally, the nursing appointment exists, but in practice, it works ineffectively.

We must not only verbally but also in practice raise the status of the nurse as an equal partner to the doctor.

There are many problems, and they are all related to the overall level of funding. Due to insufficient funding, salaries are low. At one of the recent conferences in Bishkek, Professor M.O. Favorov, who works in Atlanta (USA), presented comparative data: in the USA, 16.7% of GDP is spent on healthcare, in Germany, Russia, China — significantly more than we do. And in Kyrgyzstan, this figure is about 5.4-7.5% of total expenditures, considering both public and private funds. Government funding is about 2.5% of GDP.

According to international standards, a healthcare system cannot function properly with less than 5%. This means that we are already living in conditions where government funding is half the minimum acceptable level. The system operates on the fact that half of all expenses are covered by out-of-pocket payments from the population. This is evident when people are forced to sell property or raise funds for treatment in severe illnesses.

- In all our concepts, programs, and strategies, the development of the primary level is a priority. But often the population itself does not support this. Here, if something hurts, we immediately go to hospitals.

- This is due to the fact that family medicine lacks sufficient authority. The primary level must have several fundamental positions. First: any person should have the opportunity to seek help.

If a person can be fully helped at the primary level, there is no point in sending them further. For example, in England, Europe, and the USA, a person cannot be accepted anywhere without a referral from a family doctor. This is related to high costs and the need to rationally organize the system.

We do not have such a regulatory function for family doctors. Therefore, a patient can immediately turn to a specialist or an inpatient facility. Or even directly to the Cardiology Center. As a result, queues form in republican centers, and people take places from early morning. There are those who genuinely need help and those who came simply because they do not want to go to a family doctor. Some do not have a serious illness; they just want to talk, to be reassured, to explain. This creates an overload of the secondary and tertiary levels.

In England, all these issues are resolved at the primary level. The doctor has the right not to refer. Of course, everything must be justified. This allows the secondary and tertiary levels of healthcare to operate more efficiently. In our case, the secondary level becomes overloaded and begins to duplicate the functions of the primary. Highly qualified specialists are forced to perform tasks that a nurse could solve. As a result, the efficiency of the system decreases.

At the same time, the costs of medical care also increase. Specialists need to delve deeper into their field, prescribe more tests and diagnostic procedures. Ultimately, a patient who goes directly to a specialist spends more on diagnostics and treatment.

There are scientific studies showing that if the number of specialists exceeds the optimal level, and the number of family doctors is below the necessary level, the fragmentation of medical care increases, which can lead to higher mortality in the region.

As for organization — there are also questions here. In a recent report by Professor M.O. Favorov from Atlanta (USA), a ranking of countries with the highest expenditures and best healthcare indicators was presented.

High expenditures are not yet a guarantee of better healthcare. Of course, there is a general pattern: the higher the expenditure, the higher the expected efficiency. But among the ten countries with the highest expenditures, the USA spends the most, yet their efficiency is lower. Countries like Germany show the opposite: their expenditures are about half of those in the USA, yet their efficiency is higher. Of the ten leading countries, nine have lower expenditures but higher results. This is primarily due to the organization of the system and the effective operation of the primary level. This is especially evident in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Sweden: lower expenditures, higher efficiency.

Therefore, money is important, but the structure of the system and its operation are equally significant.

- Plans include the construction of a new medical town, where national centers are expected to be relocated. This should strengthen the role of the primary level.

- Honestly, it is difficult to say whether these plans are justified by serious calculations. Often, decisions are made first, and then it turns out that the consequences are not taken into account.

For example, a reform was carried out — institutions were merged. If we take the year 2000, there were 64 family medicine centers. In 2021-2022, the centers were consolidated, merging them with territorial hospitals, and were renamed general practice centers.

Family medicine centers lost their legal independence and became ordinary departments of the COVP. The directors of the COVP, of course, prioritize the inpatient facilities. Financial resources intended for the primary level are now subordinated to their interests and often go to maintaining the building and purchasing expensive equipment.

But equipment alone does not solve the problem. I travel a lot around the country and sometimes see complex and expensive equipment in district hospitals that is not used because there is a lack of trained specialists. Even for a regular appointment, there are not enough doctors, let alone working with such equipment.

The situation is indeed complicated. There is much talk about changes, events are held, but real changes are almost non-existent.

There are, for example, initiatives to reduce out-of-pocket expenses for medical care. But how to implement them if government expenditures remain minimal? At conferences and round tables that have repeatedly been held with the participation of the Ministry of Health, UNICEF, and WHO, it has been emphasized that for the last 15-20 years, healthcare funding in Kyrgyzstan has remained critically low, and the population is forced to cover expenses out of their own pockets.

- You mentioned the example of Europe, where efficiency is higher despite lower expenditures compared to the USA. Is it true that a large portion of funding there goes to the primary level?

- Yes, about 50-60% of funding is indeed directed to the primary level, while secondary and tertiary levels receive about 20-30%.

Of course, the conditions there and here differ. This requires serious scientific analysis. But the problem is different: in the West, there are two major scientific specialties: general medical practice (family medicine) and nursing. Both are recognized as scientific fields.

What does this mean? Research is conducted, specialists are prepared, there are candidates and doctors of sciences in the fields of family medicine, nursing, and other related areas. We do not have such specialties; they are considered "secondary." As a result, these areas remain insufficiently studied.

Ultimately, we have what we have: we merge institutions and then discuss the need for their optimization again.

In general, the primary level should be independent so that it can be analyzed and properly funded. And when everything is merged, for example, family medicine centers and territorial hospitals at the district level, it becomes difficult to even calculate the real expenses. Meanwhile, only 2.5% of GDP is allocated to healthcare.

Our Minister of Health, Erkin Checheybaev, is a knowledgeable specialist who understands the laws of global health and openly speaks about these problems. Not everyone likes this. But the laws of global health prove that adequate funding is necessary to ensure decent healthcare.

- The problem of personnel shortages has existed for a long time. How can it be solved?

- You can build a new hospital and purchase equipment, but it is impossible to "import" ready specialists, especially doctors. Training a good doctor takes at least 10-15 years: 6 years of university education, then 2 to 5 years of residency, and then continuous education is necessary; otherwise, the doctor will fall behind. Abroad, primary training also lasts up to 10-15 years. And half of the active doctors here are retirees. In 5-10 years, they will leave, and young people are not entering the profession because they understand: the conditions are tough, salaries are low, and prospects are unclear.

- We also have a mandatory five-year service.

- This may deter young specialists even more. Instead of supporting them, they are being forced to stay. It turns out: "endure 5 years for 10-15 thousand, and then we'll see."

As a result, we see a decrease in the number of doctors, an increase in workload, and the system continues to stagnate. The situation is indeed serious.

Read also:

"Doctors Vote with Their Feet". Why Family Medicine is in Crisis and How to Resolve the Situation

The healthcare reform in Kyrgyzstan was initially aimed at developing family medicine, but at the...

Why Family Medicine is in Crisis (and How It Affects Our Health)

The healthcare reform initiated in Kyrgyzstan has focused on family medicine. However, this...

The best primary healthcare organizations in Bishkek received gifts and equipment.

On April 1, 2015, in Bishkek at the "City hotel," a meeting was held to mark the end of...

The FOMS reminds about the possibility of free medical assistance in state hospitals

The Mandatory Health Insurance Fund (MHIF), operating under the auspices of the Ministry of Health,...

In Naryn, the number of doctors who have resigned was announced

In the first nine months of the current year, there have been changes in the staffing of medical...

Kyrgyzstanis are once again urged to undergo testing for viral hepatitis and get vaccinated

In Kyrgyzstan, the initiative for free testing and treatment of viral hepatitis B and C continues,...

They Don't Take Pills. In the Kyrgyz Republic, Patient Management for Hypertension and Diabetes is Evaluated

In Kyrgyzstan, a comprehensive assessment of the quality of care for patients with hypertension and...

The Minister of Health Familiarized Himself with the "Arashan" Central Outpatient Clinic

On October 25, Minister of Health Erkin Checheybaev made a working trip to the "Arashan"...

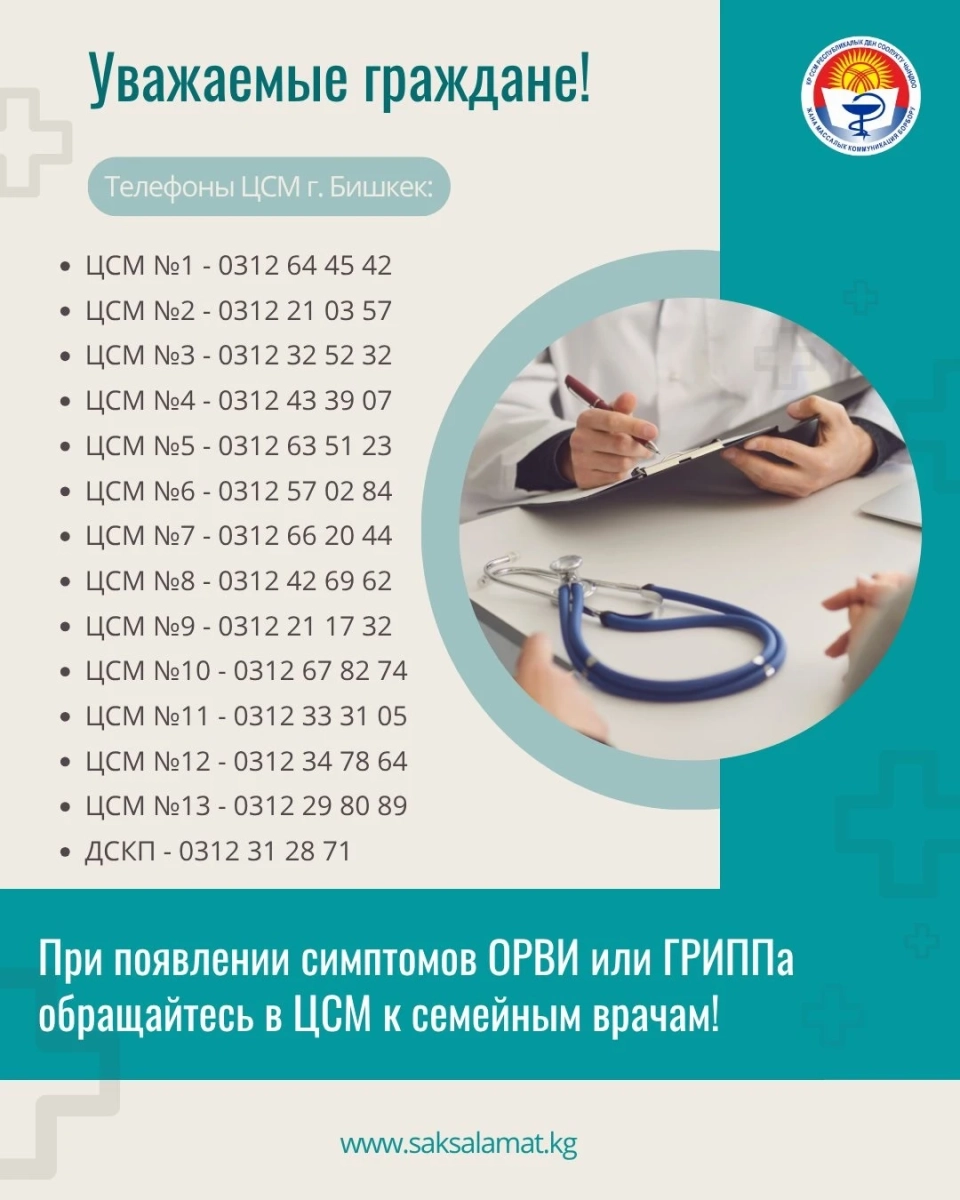

Increase in ARVI Incidence. Work Schedule of Bishkek Clinics and Current Phone Numbers

In Bishkek, family medicine centers continue to operate on weekends, according to information from...

A large-scale assessment of the quality of patient management with hypertension and diabetes has been conducted in primary healthcare organizations in Kyrgyzstan.

In the capital of Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, a Round Table and strategic meeting took place, dedicated...

In Kyrgyzstan, there are 13.6 thousand doctors and 33.7 thousand mid-level medical personnel.

According to data from the National Statistical Committee, as of 2024, there are 13,676 doctors in...

Seasonal Diseases. What Medical Services in the Kyrgyz Republic are Free and Discounted, as Reminded by the FOMS

In connection with the onset of the autumn-winter period, the Mandatory Health Insurance Fund...

There is a severe shortage of doctors in the Batken region, especially in the Batken district.

The Batken region is lacking almost 100 doctors. This information was announced at a meeting of the...

The Incidence of Diabetes Mellitus is Rising in Kyrgyzstan

According to the latest data, about 90,000 people suffering from diabetes are registered in...

Zonal Training for Healthcare Workers Kicks Off in Kyrgyzstan as Part of the Catch-Up Immunization Campaign

As part of the training, healthcare workers will gain knowledge on how to effectively catch up on...

In the city of Manas, 4 people were trapped in an elevator: Rescuers helped them

Four citizens became trapped in an elevator in Manas, located in the Jalal-Abad region. This...

Flu and ARVI Season. FOMS Reminds What Medical Services Are Provided for Free

The Mandatory Health Insurance Fund (MHIF) reminds that with the onset of autumn and winter, there...

The FOMS Reminded About the Importance of Health Care in the Autumn-Winter Period

In connection with the increase in cases of colds and viral diseases during the autumn-winter...

Construction of a new building for the regional family medicine center has begun in Naryn

During the ceremony dedicated to the laying of the foundation, the Minister of Health of the...

Checheybaev spoke about the construction of the medical city in Bishkek - plans, timelines, and which clinics will relocate

A medical city is planned to be built in Bishkek, with the start date set for 2026. This was...

Turkish Transplantation Doctors Arrived in the City of Manas

A reception for patients was held in Manas with the participation of specialists from Turkey...

The WHO mission to develop a strategy for the prevention of non-communicable diseases has begun its work in Kyrgyzstan.

The mission also includes leading experts in public health, NCD prevention, and digitalization,...

Bleeding and sepsis - the main causes of maternal mortality in 2024

In 2023, Kyrgyzstan registered 38 cases of maternal mortality, while in 2024 this number decreased...

Increase in ARVI and influenza. Contacts of family medicine centers in Bishkek

According to the data from the Republican Center for Health Strengthening, it is recommended to...

In a car accident, ophthalmologist Gulnura Maatkerimova died.

In the Naryn region, as a result of a traffic accident, ophthalmologist Gulnura Zholdubaevna...

A Waiting Room Opened in the Central Medical Center in the Jayil District

Today, November 12, a new waiting room was opened at the laboratory of the Family Medicine Center...

How to Save Patients with Myocardial Infarction Now? Opinion of Professor Igor Pershukov

Myocardial infarction continues to be one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, including...

The incidence of ARVI in Kyrgyzstan is rising. Mainly children are getting sick.

According to information provided by the Department of Disease Prevention and State...

"Resuscitation - the Last Hope": Why Are Doctors Leaving Naryn?

Zhyrgalbek Aaliyev, a doctor with 37 years of experience, works in Naryn. For eight years, he held...

In Naryn Region, a capsule was laid for the construction of the maternity ward building of the regional hospital.

On October 23, the Deputy Prime Minister and head of the State National Security Committee,...

The state will take full control over medical education and science

A draft law "On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Kyrgyz Republic in the Fields of...

Master Plan: The Business Center "Bishkek-City" is Set to be Concentrated in the Lenin District

In Bishkek, the city hall presented the General Plan, which will be in effect until 2050, and...

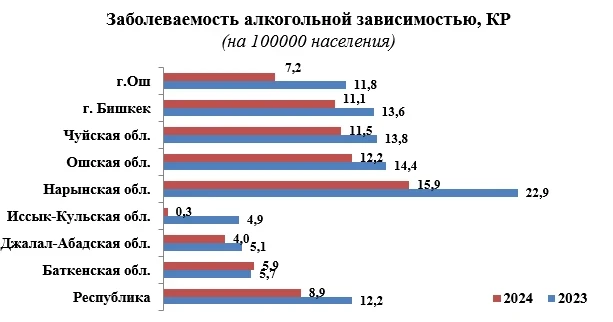

In Kyrgyzstan, Alcohol Dependency is Decreasing, with the Exception of Batken

In Kyrgyzstan, a significant decrease in cases of alcohol dependence is observed in 2024 — by 27...

Medical equipment worth $109,000 will be transferred to primary care centers.

The Ministry of Health announced the transfer of medical equipment worth $109,200 to two primary...

Kyrgyz Doctors to Undergo Training in France under Emergency Medicine Program

The cooperation agreement between the National Hospital and the Embassy of France in Kyrgyzstan...

Kyrgyzstan Presented Its Experience in the Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases at the 75th Session of the WHO European Regional Committee

At the 75th session of the European Regional Committee of the World Health Organization, taking...

Doctors from Kyrgyzstan underwent training in St. Petersburg on abdominal surgery

A group of doctors from the Osh Interregional United Clinical Hospital completed an internship in...

Doctors of the Kyrgyz Republic propose increasing excise taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks

In Bishkek, a presentation of the investment justification dedicated to the prevention and control...

Erkin Checheybaev checked the work of the "Arashan" General Practice Center

During his visit, the Minister of Health familiarized himself with the work of the institution,...

API error: HTTP 429

API error: HTTP 429...

In the Uch-Korgon Hospital of the Kadamjai District, parking lots and internal roads were paved for 4.9 million soms.

In the Center for General Medical Practice in Uch-Korgon, Kadamjay District, the work on paving the...

The outstanding doctor Orozaly Kochorov has passed away.

On November 5, 2025, at the age of 69, Orozaly Kochorov passed away — a talented surgeon and...