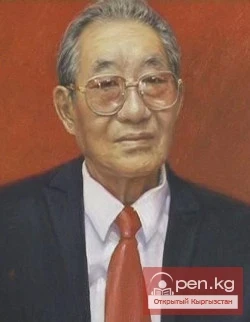

CHINGIZ AITMATOV

To know your heroes... Nowhere, perhaps, are national heroes loved and revered as much as in Kyrgyzstan. This is also a folk tradition. In any distant village, like a close relative, they will tell you about the strength and bravery, justice and resilience of the national baatyrs — heroes. Children are named after them, songs and tales are composed in their honor, and they are surrounded by legends... And why is that? Because they triumphed in competitions — sometimes through agility, sometimes through cunning, sometimes through strength — against their not-so-favorable opponents. That is why the interest in all kinds of martial arts is sincere and boundless. Try proposing any competitive event — and you will immediately find a multitude of spectators, fans, and advisors.

Folk games and physical exercises often represent a valuable, crystallized over the centuries means of comprehensive physical and moral development for the youth. They deserve to be preserved as carefully as we preserve folk dances, melodies, and songs. It should not be forgotten that from among the youth engaged in national sports, strong, willful athletes emerge.

Among the Kyrgyz, people of great physical and spiritual strength, agile, brave, and hardened, capable of enduring any hardships, have been respected and celebrated since ancient times.

By creating hyperbolic images in the figures of Manas, Semetey, Seytek, and other heroes, the Kyrgyz people aimed to raise the youth to be healthy, strong, agile, fearless, and resilient.

The Kyrgyz people have gone through a difficult path in their development. Many times, during invasions and plundering campaigns by foreigners, the Kyrgyz defended their land and national independence in unequal struggles.

In the most challenging conditions, this people not only withstood and repelled the assaults of conquerors but also preserved their unity, developed, and brought to our time their multifaceted culture of songs and tales, monumental heroic epics, unique applied arts, physical exercises, games, and heroic competitions.

Emerging in deep antiquity, the physical culture of the Kyrgyz was an inseparable part of the life and everyday existence of the people.

The constant military raids that the Kyrgyz had to repel for many centuries, along with their nomadic lifestyle, demanded great courage, strength, and agility from men. In this regard, the emergence of competitions with a military-physical character becomes understandable — er sayysh — the duel of two horsemen with spears, oodarysh — wrestling on horseback, and jamby atmay — archery while riding at a gallop at a suspended target.

The most ancient of the militarized sports is er sayysh. Two horsemen, armed with spears, attack each other at high speed with the aim of piercing the “opponent” and unseating him. The blows of the opponents were so strong that their horses would sink back on their hind legs. Often the outcome of the duel was fatal, which is why only brave, agile people who were not afraid of possible death participated in er sayysh. No one was held accountable for the death or injury of participants; the organizers of the event cared little about this. The great Kyrgyz akyn Toktogul wrote about this brutal form of competition:

And the manaps laugh, the manaps shout.

They are pleased that the fight ends in death.

May such a custom sink into the ground!

The life of a nomad was unimaginable without a horse. It is no coincidence that various horse games and equestrian competitions became widespread among the Kyrgyz — at chabysh (races), jorgo salysh (competitions on pacers), ulak tartysh (struggle for a goat carcass), tyin enmey (picking up a coin from the ground while riding) and many others. Success in them often depended on the preparation of the horse and the rider's ability to control it at a critical moment.

The next group of games of the Kyrgyz people consisted of male competitions and board games — kurash (wrestling), ordo (a game with alchiks in babki), toguz korgol (9 holes — Kyrgyz chess), upai (a game with alchiks) and others.

Separately, one can highlight competitions related to hunting with a golden eagle or falcon, and hunting with a taigan.

Among the Kyrgyz youth and children, active games were popular — ak chölmök, chaka chapmay, jooluk tashtamay, ak tere — kok tere and many others. These games were part of the overall culture of the people and widely reflected their way of life. It should be noted that many of this group of games are similar to games of other peoples from the East and West. Clearly, they arose as a result of communication with them, especially with the Russian people.

And finally, the last group consisted of games that served as entertainment for the wealthy class — tyo chechmey (untying a camel by a naked woman), atala bash (picking up coins with the mouth from a pot filled with milk) and others.

These games, humiliating the dignity of participants, once again emphasized the class essence of the organizers of the competitions.

The living conditions and lifestyle of the Kyrgyz turned physical culture into one of the main factors in educating children and youth in strength and agility, endurance and courage, and other qualities necessary for a warrior.

As scientific research has shown, during the circumcision ceremony, boys at the age of three were placed on a horse — this was the first step in teaching the child to ride.

In some regions of Kyrgyzstan, Kyrgyz boys up to the age of six initially learned to ride on rams, later on colts. The Kyrgyz even had a special type of children's saddle (ynyrchak), which allowed the child to learn to ride independently.

After the age of six, boys began hunting small game, spending nights in the mountains under harsh conditions, far from their native aul, mastering the art of rock climbing, covering long distances on foot and horseback, and learning to navigate at night.

Such a system of physical training allowed children to participate in competitions as early as six to eight years old, especially in equestrian events.

An interesting fact, reflected in the national epic and confirmed in conversations with the oldest connoisseurs of folk competitions and games in various regions of Kyrgyzstan, is the adherence to a special diet and daily routine by participants before competitions, with both the diet and daily routine varying depending on the age of the participant and the program of the competitions.

Particularly great attention was paid to diet and daily routine by those participants who competed in equestrian events.

In competitions, healthy boys, but with a slight weight, participated. A few days before the competitions, boys were fed exclusively calorie-rich foods: meat, milk, and sour milk.

Before the competitions, the boy would have a light breakfast to maintain lightness and ease the work for the horse.

Men prepared differently, especially for wrestling competitions. Here, in addition to calorie-rich foods: lamb meat, kumys, etc., the wrestler's weight was increased. Moreover, all participants in the competitions, without exception, avoided consuming bozo (an alcoholic drink): it was believed to cause shortness of breath.

Warming up before participating in competitions was mandatory. We find mention of this in the “Manas”: “vigor for the duel is needed, for vigor, warming up is needed.” Often, warming up was conducted in the form of massage.

It is characteristic that girls and women participated widely in the folk competitions and games of the Kyrgyz.

Thus, the character and content of national sports in pre-revolutionary Kyrgyzstan were closely related to the socio-economic and domestic way of life. Although it was the people who created the competitions and games, they had a class character. This was due, firstly, to the fact that the festivities where competitions and games were held could only be organized by the bai and manaps. They were able to invite many guests and allocate large prizes for the winners. Secondly, by timing the competitions to religious holidays and various ceremonies (weddings, funerals, etc.), the wealthy elite used them for their own interests.

The organization of such festivities placed a heavy burden on the shoulders of the poor.

One of the prominent Russian researchers, ethnographer Burov-Petrov, wrote: “The funeral for the famous manap Shabdan (1912) cost each poor household 21 rubles and each middle-class household 50 rubles. In addition to the colossal collection for large prizes for the races, every 5 yurts had to accommodate, feed, and provide drinks for up to 30 guests during the funeral. In total, at this funeral, according to the testimonies of living participants, about 10,000 sheep were slaughtered and a significant number of horses were prepared to feast the guests.”

At-chabysh

Ulak-tartysh (goat dragging)

Oodarysh

Kyz kuumay

Jamby atmay

Tyin enmey

Kurash

Ordo — khan's stake

Toguz korgol (toguz kumalak)

Alty bakan selkinchek and Dumpuldak

Arkan tartmay (tug-of-war)

Achakei-jumakei and Chaka chapmay

Teke chabysh

Chakan atmay (chakan stone)

Upai

Besh tash

Jooluk tashtamay

Ak cholmok

Burkutchi (hunting with an eagle)

Other games (see next page)