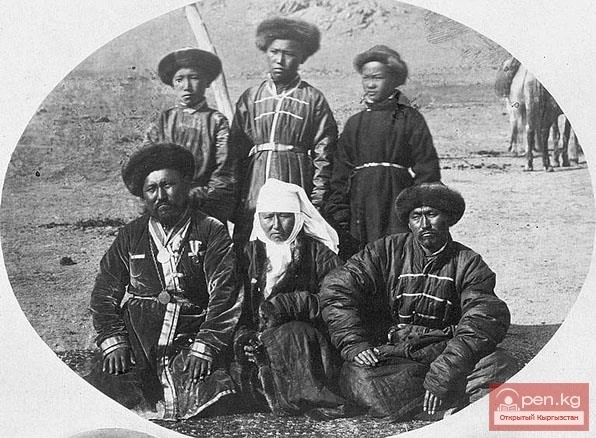

Family and marital relations among the Kyrgyz in the past were closely dependent on patriarchal-feudal relations. The dominant form of family was the individual (small) family. However, it still retained many features of its predecessor—the patriarchal family—and was not the only form of family.

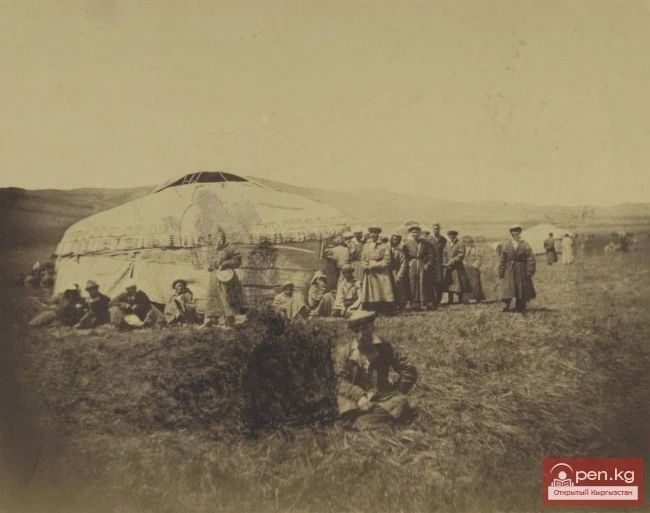

There is reliable information that in the 19th century, alongside the small family, a significant number of undivided large families continued to exist among the Kyrgyz, externally possessing many characteristics of patriarchal family communities, the process of disintegration of which had begun long ago. They consisted of relatives from three generations or more, living under a common household; the number of members in such families reached several dozen people. Livestock was considered a common family asset, and food supplies, as well as meals, were shared.

The preservation of this form of large family was associated with the growth of property inequality. The development of family property and its accumulation required replenishment of large households with labor. The hiring of labor in the context of the dominance of natural economy could not gain any significant spread. The patriarchal slavery that still existed in the first half of the 19th century could not fully satisfy the needs for labor either. Naturally, in these conditions, family cooperation gained great importance in large households. It is not accidental, but rather quite logical, that economically, large undivided families were usually quite prosperous.

The disintegration of the natural economy and the growth of its commodity nature, especially in connection with the penetration of capitalist relations into the Kyrgyz aiyl, subsequently led to the disintegration of the remnants of large family communities. However, this disintegration usually did not end with the complete separation of small families. They formed groups of related families, primarily united by the consciousness of descent from a common ancestor in the third or fourth, and more rarely in the fifth generations. Within such groups, close economic, domestic, and ideological ties were maintained between families. Customs of material assistance to relatives in paying kalym, in expenses related to funerals and memorials were characteristic of these groups. There was a special type of burial structures for the burial of close relatives.

The small family usually consisted of the head of the family, his wife, and children, sometimes also parents. Polygamy was widespread mainly in the families of manaps and generally in wealthy and prosperous families; poor families were usually monogamous. In the households of the wealthy, polygamy often represented a peculiar form of exploitation of women's labor.

Marriage was preceded by matchmaking. There was a custom according to which newly born infants were often betrothed, and sometimes even unborn children were the subject of the agreement. This custom was more characteristic of wealthy families. Common forms of marriage included the remarriage of a widow to the younger brother of her deceased husband and the marriage of a widower to the younger sister of his deceased wife.

Among the poor, there was also a form of marriage known as the exchange of sisters or female relatives without the payment of kalym. Finally, sometimes (though rarely) the abduction of girls was practiced. In most cases, it occurred with the girl's consent. Abduction did not exempt from the payment of kalym.

Most often, marriage was characterized as a transaction between the parents of the young man and the young woman, based on the payment of a bride price (kalym) for the bride. The consent of the young man and young woman was usually not required for marriage. The payment of kalym, which was a mandatory condition for marriage, was extremely difficult for the impoverished segments of the population, hired shepherds, and the poor. Often, the poor were doomed to remain unmarried because of this. Even in middle-class families, the payment of kalym was often a matter for the entire family-kin group to which the groom belonged. The amounts of kalym varied, depending on the wealth of the families of the groom and bride. Kalym was somewhat compensated by the dowry (sep), which in wealthy families included a yurt for the newlyweds; usually, it consisted of clothing, jewelry, household furnishings, and utensils. Occasionally, labor was worked off for the bride: the groom worked for several years in her father's household.

Early marriages were common. Girls aged 13-15 were married off. Parental authority often led to boys marrying adult women, while 9-10-year-old girls became wives of elderly men.

Among the Kyrgyz, exogamy was preserved, but it had a "generational" character: in the past, by custom, it was allowed to take a wife from a relative's family along the male line no closer than the seventh generation; however, this restriction gradually began to fade in some places. In the Kyrgyz family, only kinship along the male line had real significance, although some traces of older family-marital relations associated with maternal rights remained. Cousin marriages were common among the Kyrgyz. Literature (N. P. Dyrenkova) noted that among the Kyrgyz, only one-sided cousin marriage was practiced—with the daughter of the mother's brother. Indeed, marriages with maternal relatives, including marriages between children of sisters and even marriages with the mother's sister, were particularly preferred. However, as early as 1948, it was established that among the Kyrgyz, marriages with the daughter of the father's sister also occurred, albeit less frequently. Thus, it can be considered that among the Kyrgyz, cross-cousin marriage existed. At the same time, in some tribes in southern Kyrgyzstan, marriages between close relatives along the male line were practiced, which cannot be overlooked as an influence of Sharia norms.

Among maternal relatives, special attention was given to the mother's brother, who had certain rights and responsibilities towards his sister's children. He was held in special respect by them. The brother of the bride and the brother of the groom played an important role in the wedding ceremony. The maternal relatives showed special affection towards their female-line nephews. During weddings and other celebrations, guest-nephews were distinguished in a special group, special treats (zheen ayak) were arranged for them, and they were given gifts. Alongside this, the nephew also enjoyed significant rights. His right to receive gifts from his maternal uncle is reflected in the Kyrgyz proverb: "Better let seven wolves come than a nephew."

In addition to the customs of levirate and sororate, the Kyrgyz had other customs indicating ancient forms of marriage. Thus, the elders preserved memories of once-existing peculiar extramarital relationships permitted by custom: the younger brother had the right to engage in extramarital cohabitation with his older brother's wife. Such relationships represented remnants of a special form of marriage that preceded monogamous marriage and the emergence of levirate and sororate norms. Similar forms of extramarital relationships were noted by I. P. Potapov and among some peoples of Altai. Certain customs also clearly exhibited remnants of marriage characterized by matrilocal residence. Such is the custom of pre-marital visits of the groom to the bride (kuivvllv). After the first meeting with the bride, which took place in her father's aiyl, the groom would come here completely openly, avoiding only encounters with the bride's older relatives. The important role in these visits belonged to the bride's female relatives. The period of pre-wedding visits by the groom was, in the distant past, nothing more than the actual beginning of married life, the marriage itself. The groom's visits were accompanied by various rituals and customs. In southern Kyrgyzstan, customs of the young woman living for a long time after the wedding in her father's house, where her husband would come only from time to time, were common. The custom of the young woman visiting her parents—terku lev, which occurred a year after the wedding—was also widespread. This was one of the varieties of the well-known custom of "returning home."

In the terminology of kinship among the Kyrgyz, features of a classificatory system are still preserved. It includes a significant number of terms, each of which refers to a whole group of people.

Relations in the Kyrgyz family were built on a patriarchal basis. The head of the family was considered the administrator of all property and the fate of his children. The position of women in the family, as well as in society, was unequal. The blood money—kun—for the murder or injury of a woman was paid at half the rate. Women could not be, with rare exceptions, witnesses in court. They did not have property rights and were effectively deprived of inheritance rights. After the death of a husband or father, a woman was regarded as part of the property that passed to the husband's relatives or brothers. In the case of divorce, children were to remain with the father. At the same time, the woman was the main labor force in the family, performing all tasks related to household management, child-rearing, caring for livestock, and making clothing and utensils. All this heavy burden fell on the Kyrgyz woman and led her to premature aging. Customs such as marrying off minors, kalym, and polygamy were humiliating for Kyrgyz women, reducing them to the status of slaves.

It should be noted, however, that while under complete guardianship and subordination to men, Kyrgyz women still enjoyed some freedom and independence in domestic life and household management. In poor families, they were much less powerless than in wealthy and prosperous families, serving as helpers and advisors to their husbands in all economic and family matters. In the distant past, women in Kyrgyz society, as can be judged from folklore data, held a higher position.

As a result of deep revolutionary transformations in social relations, carried out in our country under the guidance of the Communist Party, the old patriarchal family relations were broken down to the same extent as other aspects of life. Collective farm construction and industrial development, accompanied by the wide involvement of Kyrgyz women in socially useful labor, brought them economic independence, which ensured their equal status in the family. This, in turn, became a major factor that caused profound changes in family-marital relations, leading to the emergence of a new type of family—the Kyrgyz Soviet family.

A significant feature of the new type of family-marital relations is the conclusion of marriages initiated by the young people themselves, based on their mutual inclination and love, which parents usually do not hinder. This was greatly facilitated by the fact that the humiliating custom of paying kalym was prohibited by law. However, it should be noted that in some places, remnants of kalym still persist, albeit in hidden or disguised forms. Marriages are formalized in accordance with the procedure established by Soviet law—through registration in the civil registry office, although traditionally, in many families, a Muslim marriage ceremony is also performed.

Thus, modern marriage has generally lost its previous character as a transaction between the parents of the young man and the young woman. The number of marriages concluded at the insistence of parents is decreasing. If the bride's parents do not consent to the marriage with her chosen one, intending to marry her off to someone else, the young people negotiate, and the groom secretly takes the bride to his home. This method of concluding marriage has nothing in common with the occasional cases of abduction of girls without their consent for the purpose of marriage. This intolerable phenomenon in Soviet society is met with resolute opposition.

The customs of parental matchmaking for the future marriage of children still in the cradle have disappeared. The disgraceful custom of levirate has also ceased to exist.

In the past, when exogamous marriage prohibitions were firmly maintained, wives were often brought from afar. Now many young people take wives from within their own village, as with the transition to a sedentary lifestyle, in many cases, groups of different origins settled in one village or collective farm, making marriages between close neighbors possible without violating traditional prohibitions. This undoubtedly contributes to the strengthening of marriages, as young people usually know each other well from childhood, having studied together in school and worked together in production.

Significant progress has been made in the fight against early marriages, which were previously widespread, although individual cases of marriages with underage girls still occur. In Soviet conditions, the principle of monogamy has become absolutely dominant. The ugly remnants of polygamy, which sometimes appear, are being combated by Soviet society and judicial authorities.

One of the important consequences of establishing new national relations based on friendship among peoples and brotherly cooperation between them is the emergence of mixed marriages. Such marriages, for example, between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks, existed before, but now they have become commonplace. Marriages between Kyrgyz and Russians are no longer rare, as they were before. This indicates the overcoming of former national and religious isolation. Mixed Kyrgyz-Russian families, where the husbands are Kyrgyz and the wives are Russian, serve as conduits for many cultural skills, advanced forms of domestic life and family customs characteristic of Russians.

The wedding is a significant event not only for the families of the marrying couple but also for a fairly wide circle of relatives. The collective farm active members usually participate as well. Many traditional elements are still preserved in wedding customs. However, these customs often appear in significantly altered forms. In the past, the solemn celebration of weddings was accessible only to the wealthy part of the population. Now, most collective farm families have the opportunity to celebrate them lavishly. Although it has changed, the custom of matchmaking still exists. Quite often, the girl moves to the future husband's house soon after the negotiations between the parties are completed, without waiting for the mandatory wedding feast in the bride's father's house, as was required in the past. In cases where the wedding takes place in the bride's father's house, such ceremonies are observed as inspecting the dowry, dressing the groom in a new outfit gifted by the bride's parents. Youth games (kyz oyun) are organized. The most popular game is tokmok saluu, during which young people perform lyrical songs, jokes, and improvised pieces. Before the young bride departs, she says goodbye to her mother and other female relatives and friends.

When the groom goes to fetch the bride to arrange a feast in his house, he is accompanied by several friends who perform the functions of groomsmen (kuive zholdosh). They are to present gifts (zhegita) to the bride's female relatives, often in the form of money. The bride usually takes with her the most necessary clothing and, importantly, a wedding curtain (kushak).

Along the way in southern Kyrgyzstan, sometimes children and teenagers stretch a rope across the road. To clear the way, they are given small coins.

The arriving guests are met by the groom's mother, who showers the newlyweds with homemade pastries, uttering well-wishes. Upon arriving at the husband's house, the bride sometimes still sits behind the curtain for several days. Relatives and acquaintances of the husband's family come into the house to see the bride and make a gift for the viewing—kvrumduk.

The wedding feast—toi—is usually held very solemnly. Sometimes it is first organized for representatives of the older generation and honored guests, and then for married peers and friends from the youth. In addition to abundant treats, sequential singing is organized, games are held, and a gramophone is played. Sometimes artists and musicians are invited to the wedding, who perform works of folk music.

Close relatives of the groom play a significant role in the expenses for the wedding feast, as well as in other wedding expenses. A prominent place in wedding ceremonies still occupies the mutual exchange of gifts between the families of the marrying couple. The dowry, in which the bride herself participates in its preparation, includes household items (blankets, felt carpets, decorative embroidered panels, wedding curtains) and clothing for the bride (several dresses, a coat, a jacket, shoes). The dowry is most often brought by the bride's mother after the wedding. However, the delivery of the dowry is usually preceded by a visit from the groom's parents and his relatives to the bride's parents. They bring gifts for the relatives of the bride's family.

The change in the nature of marital relations, which reflects the growing independence of Kyrgyz youth and their new Soviet worldview, has positively influenced the entire structure of family life.

Significant progress is noted in the very form of the family. Indeed, the custom of living in large undivided families is still somewhat preserved: in every village, one can meet families where a father lives together with several married sons or two married brothers. However, the small family has become the predominant, typical form. Its establishment as the absolutely dominant form of family has contributed to the liberation of family relations from the characteristics of patriarchality inherent in undivided families. This is a positive and significant step in the development of the Kyrgyz family, especially felt by women.

In undivided families, there are sometimes up to 15 members. In their internal structure, one can observe a more clearly expressed authority of the head of the family. But in these families, material and labor mutual assistance is developed, facilitating the participation of their members in social labor. Separate undivided families have also been registered among Kyrgyz workers-miners.

Among the Kyrgyz, families of medium size, consisting of four to five people, predominate. However, a significant percentage consists of families with six members or more. A characteristic feature of the Kyrgyz family is the strength of kinship ties; therefore, it is customary to include certain close, and sometimes even distant relatives, who for some reason have lost their family home (an adult brother or sister of the head of the family, a brother or sister of the father, a widow of a brother or father’s brother, a son or daughter of a brother or sister, children of a father’s or mother’s brother).

Currently, one can often observe a peculiar "splitting" of the family, more often a large undivided one, into two parts, separated territorially for seven to eight months a year (and sometimes year-round), but connected by both family-kinship ties and interests of a common household. Some members of such a family work on a livestock farm and are with the livestock in summer pastures, while the other part is in a field brigade. These families have to live "in two homes," which imposes a certain imprint on their domestic life. The need to divide the family into two parts is often caused by the presence of school-age children living in the village. At the same time, other livestock families live in full composition outside the village in distant pastures for many years.

The economic foundation of the family has changed completely, which has also altered the nature of intra-family relations. In the past, all family structures were determined by the principle of private ownership of the means of production. With the transition of all means of production to public ownership and the establishment of the undisputed dominance of the socialist system of economy, the Kyrgyz Soviet family, while still retaining some economic functions, directs its main efforts not to the development of private household (its own or someone else's) but to the development of socialist production. Therefore, the basis of the family's material well-being consists of the incomes obtained from the participation of its members in public production. Secondary are the incomes from personal households. All these types of income now serve to meet the ever-increasing diverse personal needs of collective farmers and their families, to improve their material and cultural living standards.

Some former aspects of the family's economic life have completely disappeared, and many productive functions have been lost. Now Kyrgyz women are freed from certain types of labor that required enormous strength and time and were conditioned by the peculiarities of semi-natural individual farming and nomadic lifestyle in the past. Labor in personal households and domestic life is now distributed more evenly, as men also participate in it. Property relations are built on a new basis, in accordance with Soviet legislation. The extinction of the old customary law of inheritance of property by the deceased's brothers and male relatives is quite significant. Currently, the legal heirs are the wife and children.

The most significant indicator of the transformation of the entire internal foundation of the family is the new relationships between husband and wife, which are the result of the increasingly strengthening economic independence of women. The equal status of husband and wife, genuinely comradely relations between them, as well as a more free and independent position of youth, combined with respect for elders, have emerged in the process of overcoming the patriarchal traditions that prevailed in the old family. With the occasional cases of manifestations of feudal-bourgeois attitudes towards women and children, party organizations and the Soviet public of Kyrgyzstan are engaged in an unwavering struggle.

A diverse influence of the Russian people, their advanced culture, and communication with Russian families living nearby have played a significant role in changing intra-family relations among the Kyrgyz. This influence is particularly evident in cities and urban-type settlements, but it can be observed everywhere, including rural areas, even in the remote high mountainous regions of the republic.

In the Kyrgyz family, children are taught labor skills, instilled with a sense of responsibility, mutual assistance, attachment to the family, and respect for elders. This is why a notable characteristic of Kyrgyz family life is the strong kinship ties mentioned above. The upbringing of the younger generation, which is the most important function of the family, is carried out jointly with the Soviet school, pioneer, and Komsomol organizations. In children, love for the Motherland, for the Communist Party, loyalty to the cause of communist construction, and a sense of internationalism are nurtured. For its part, the school helps to develop the correct principles of family upbringing. Teachers, most of whom received education in cities, not only absorbed knowledge there but also the best aspects of Russian culture. In those rural areas where there are no compact masses of Russian population, collective farm families have gained an understanding of modern views on child-rearing in the family, precisely with the help of teachers. Everywhere, where the Kyrgyz population closely interacts with the Russians, the example of Russian families and the experience of long-term communication with them positively influence the upbringing of children in Kyrgyz families. The results of this influence are reflected in a more attentive attitude towards children, their needs and requests, in encouraging children's abilities in music, singing, embroidery, in a benevolent attitude towards children receiving not only secondary but also higher education, in providing schoolchildren with their "workplace" at home for doing homework, and in a stricter attitude towards the child's appearance, clothing, and tidiness.

Now it is customary to give children new names, including Russian ones. But the old tradition of reflecting particularly significant events in the surrounding life and memorable dates in children's names still persists. In the names of Kyrgyz children, one can find the names of Soviet holidays, reflecting Soviet power, the Great Patriotic War, peace, the census, migration to the summer pastures, etc. Most children's names have a traditional character.

The birth of a child is regarded in any family as a happy event. It is necessarily celebrated with a feast (zhentek), consisting of the national delicacy boorsok and flatbreads with melted butter. After five to seven days, the child is placed in a cradle (beshik). Despite the negative qualities of the cradle inherited from the old nomadic lifestyle, children's beds are still not widely spread. The first laying of the child in the cradle is accompanied by a small women's celebration (beshik toi). The cradle is smoked with the smoke of burning juniper, fat is thrown into the fire, and some other rituals are performed. A feast is also arranged on the 40th day (kyrky), when the child is dressed in a shirt sewn from 40 patches collected from neighbors and bathed in "40 spoons" of water. These and other rituals accompanying the infancy period are remnants of ancient beliefs associated with the desire to preserve the child's life, making it long and happy. They are performed in some families at the initiative of older women who influence their daughters-in-law, daughters, and other young relatives, who adhere to the established tradition without pondering the meaning of these rituals. Among the entrenched customs is the Muslim circumcision ritual performed on boys.

New customs are also entering daily life, primarily observed in the families of the intelligentsia: celebrating children's birthdays, organizing New Year trees for them. Children are bought toys and given money to attend cinema screenings.

Mothers of many children are held in great respect. The Soviet government has surrounded the Kyrgyz woman-mother, as well as other women in our country, with immense care. Benefits for mothers of many children and single mothers, free medical assistance, children's nurseries, maternity leave, and much more have created favorable conditions for increasing birth rates in Kyrgyz families and reducing child mortality.

In Kyrgyz families, where love for children is so great, one can often find adopted children, including those of healthy close relatives. During the Great Patriotic War, the adoption of Russian children by Kyrgyz families became widespread. This phenomenon manifested a new Soviet ideology based on the idea of friendship and brotherhood among peoples.

If the process of developing the old Kyrgyz family was moving towards the gradual disintegration of patriarchal ties, isolation, and individualization of the family, its strengthening as an economic unit of feudal society, then the process of developing the Kyrgyz family in Soviet society is fundamentally different and based on a new foundation. Already a monogamous family and gradually losing the features of an economic unit of society, it has transformed into an important cell of the Soviet labor collective both in the city and in the village. In contrast to the old family, the progress of the modern Kyrgyz family is characterized by the development and strengthening of its multifaceted ties with the entire socialist society. The consolidation of the principles of communist morality in family life, inextricably linked with overcoming feudal-bourgeois attitudes towards women, is of utmost importance.

Remnants of religious ideology are firmly retained in family customs associated with the burial ritual. Although all the main elements of the burial ritual are performed according to the requirements of the Muslim religion, much in it also traces back to folk tradition and beliefs stemming from the ancient cult of ancestors.

Among the Kyrgyz, funerals and memorials usually turn into a kind of public event, in which not only family members and close relatives participate but also a wide circle of distant relatives, who are specially notified if they live in other villages, districts, and cities, as well as fellow villagers. Funerals and related customs incur very large expenses.

In many rural areas, it is still customary to place the body of the deceased in a yurt, which is specially erected in the yard for this purpose, before burial. The mourning of the deceased is traditional, in which women participate, performing touching laments. They sit in the yurt where the deceased is placed. Close male relatives stand near the yurt, leaning on staffs. While relatives or those wishing to express condolences arrive, wailing and crying can be heard both inside and outside the yurt. The widow usually sits with her hair down, covered with a dark or light scarf (depending on the age of the deceased).

After the body of the deceased is washed twice, which is then wrapped in a white shroud, the ritual of absolution (dooron) is performed, and a prayer for the deceased is read. In washing, relatives (svik tamyr) from different groups (from those from whom girls were taken into the family and from those to whom girls were given in marriage from this family) are still required to participate. Representatives of other large family-kin groups present at the funeral are sometimes still given money "for the soul's commemoration" (muche).

At the cemetery, according to old custom, only men go. To this day, in many populated areas, each family-kin group has its own cemetery, but increasingly, mixed burials are now observed.

In the arrangement of graves, several variants are noted, one of which apparently traces back to the ancient so-called catacomb type of burial structures.

In northern Kyrgyzstan, the tradition of arranging earthen enclosures around graves or erecting tomb structures in the form of small mausoleums—made of adobe (molo) or raw brick (kumbaz)—is still preserved.

The burial ritual includes a specific cycle of memorials, which are performed on the third day after death (u chu luk), on the seventh day (zhetilik), and on the 40th day (kyrky). On the 40th day (or on the 20th day), close relatives visit the deceased's grave. They bring various products, which they eat near the grave. This visit is called beiit bashyna baruu (going to the fortieth). All ceremonies conclude with a memorial feast—ash, held a year after death, and sometimes earlier. Memorial feasts are often very crowded, with abundant treats, for which a lot of livestock is slaughtered. Soviet society opposes such extravagant memorials, which heavily impact the family's budget. After the memorial feast, mourning for the deceased and the observance of mourning cease.

Source: Facebook — Nasledie